Art and artifact conservators are the guardians of our cultural heritage. Their fascinating work blends art and science to protect the treasures of the past for future generations. But that work is often invisible to the public.

The American Institute for Conservation showcases this field through the annual Ask A Conservator Day. This year, NY State Parks and Historic Sites’ Department of Historic Preservation conservators Elizabeth Robson (Paintings) and Paige Schmidt (Wooden Objects) took a break from their labs to answer questions about their work.

What do conservators do? What is outside the scope of their field?

Conservators are highly skilled, highly trained professionals who care for art and artifacts. They assess the condition of a particular object and carry out a course of treatment for it. They also provide guidance on how to store and exhibit an object or work of art.

Conservators also specialize in one area of expertise, such as paintings, paper, objects, textiles, or architecture. There are further specialties within these categories, like murals, books, photographs, frames, wooden objects, archaeological objects, metals, and more. While a conservator’s treatment may improve the aesthetics of an object (e.g. replacing missing paint), they never do so at the expense of any original material. Nor do they give appraisals of artworks or artifacts.

How does one become a conservator? What kind of schooling or training do you complete?

Becoming a conservator involves many years of training, including hands-on work in various areas, often culminating in a graduate degree. Two graduate programs exist in New York at Buffalo State University and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. Others include the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation and the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage. State Parks and Historic Site conservators, Paige and Elizabeth, are both Buffalo State University graduates.

These academic programs are highly selective. “In order to be accepted into one of these graduate programs, students must study studio art, art history, and chemistry, as all of these are very important to the field of conservation,” Robson explained. “They will also usually intern in conservation labs and gain experience examining and treating objects under the supervision of a practicing conservator.”

What does an object treatment involve?

Each treatment begins with a close examination of the object, and detailed documentation, both written and photographic. “Since every object is unique, there is no singular treatment that can be applied in each case,” Robson said. “Many variables must be taken into account, and careful testing must be done before deciding what course of treatment to pursue.”

Do conservators do anything besides treatment of objects?

Conservators have many other responsibilities, including creating condition surveys of collections, conducting scientific analysis on objects, monitoring the environments in which collections are stored and exhibited, and training site staff on housekeeping and pest management. “We work collaboratively with the rest of the Bureau of Historic Sites, including curators, collections managers, and interpretation and exhibits staff to help ensure that all the collections owned by the state are safely maintained and will be able to be accessed and enjoyed many generations into the future,” Schmidt said.

How do I fix the veneer on a gateleg table? How do I restore worn stenciling on a chair? I have a chair that needs caning. Can you help?

Schmidt and Robson both emphasized that a conservator may not be who you need when seeking assistance with something in your home. If the object in question doesn’t have historical significance, if it’s still in use, and if you’re not concerned with preserving original material, the services of someone such as a furniture restorer, picture framer, or tailor may be sufficient. The American Institute for Conservation offers guidance on how to care for your personal collection, and advice on how to connect with a professional conservator.

Examining the piece in question is an essential first step, and no two treatments are the same. “For information about how to repair a decorative finish, mend breaks, or replace lost elements, a conservator would best be able to advise you after seeing the piece in person. This way, they can also discuss what your goals are for the piece, and how to achieve them,” Schmidt said. “Sometimes what looks best in the short term isn’t always the best long-term solution and can cause problems down the road.”

“For example, when repairing or replacing veneer, I always take into consideration the material and condition of the substrate, the thickness and type of veneer originally used, and how the original veneer was adhered and coated. This dictates the replacement material, adhesive, and coating I might use for the repair, since I want my work to be compatible with the original material, reversible, and stable in the long term.”

Of all the objects you’ve worked on, which is the most meaningful to you and why?

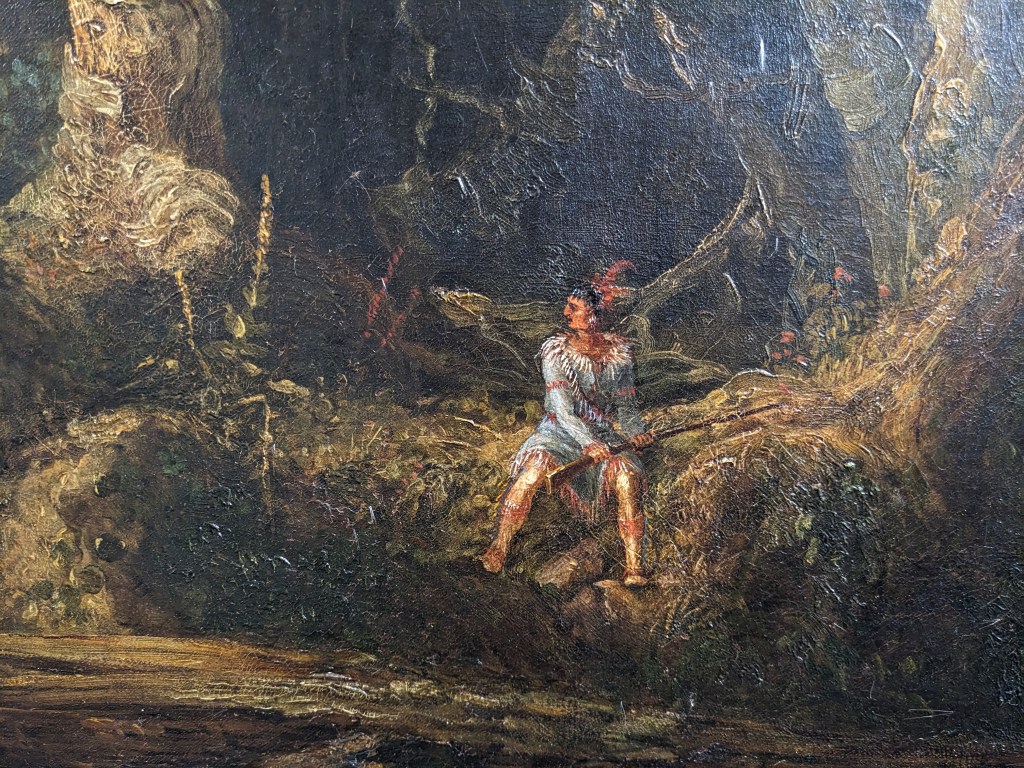

Elizabeth Robson: “In terms of the paintings I have worked on for New York State, the most meaningful one so far has been the treatment of Thomas Cole’s “A Solitary Lake in New Hampshire”. This wonderful example of a Hudson River School painting will be featured in the exhibition Native Prospects: Indigeneity and Landscape Painting at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site next year. This exhibition includes works by contemporary Indigenous artists, highlighting their knowledge and art practices, which aligns with New York State’s continued emphasis on Our Whole History. It has been a pleasure to be able to closely examine the details of this large landscape, including the Native American figure, birch bark canoe, and many-pointed stag.”

Before and during treatment images of Robson’s work on Thomas Cole’s “A Solitary Lake in New Hampshire.”

Paige Schmidt: “One of my favorite projects was the treatment of a Gebrüder Thonet rocking chair. The work involved recreating a missing back splat, repairing a partially stripped original coating, and structural stabilization. In addition to the treatment, I also analyzed the wood and coating to learn more about Thonet’s manufacturing techniques at the time. This was a particularly challenging and satisfying project because I was able to restore the chair’s original form and function while also preserving the original material present. Now when I visit New York State historic sites, I am always particularly excited to see the bentwood furniture in our collections, including great examples of Gebrüder Thonets at sites like Olana. Furniture in private collections is often highly altered over time to reflect changing fads or to keep the piece functional, so seeing relatively untouched and well-preserved examples is of great scholarly value- and just so cool!”

-Written by Kate Jenkins, Public Affairs Digital Specialist in Albany, in collaboration with Elizabeth Robson and Paige Schmidt.

One thought on “Where Art and Science Meet: A Q&A with Art Conservators”