As New York splashes the summer away, a dedicated team works behind the scenes to make sure our beaches are swim-ready.

Consisting of three permanent staff and a summer intern, the Water Quality Unit at New York State Parks is charged with coordinating water sampling at the 75 monitoring stations at 49 beaches throughout New York State. Based in Albany they work closely with other agencies to report and track their results.

Water Quality Unit team members all agree that this is a job hiding in plain sight. While it’s essential to public health and appreciated by millions every summer, it’s generally under the radar of most of the people it benefits.

“People seem surprised that this job exists,” said Veronica Mileski, Water Quality Program Specialist. “I don’t think the public really understands what goes into making sure their recreational areas are safe.”

Mileski graduated in 2023 with a degree in Aquatics and Fisheries Science with a focus on fisheries. In less than a year at Parks, she’s attended conferences, carried out fieldwork, and assisted with the Day In The Life on the Hudson educational event in collaboration with the Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC).

“I was able to help electroshock fish for the event as well as show the students how to identify certain species of fish,” she recalled. Mileski has long been interested in aquatic systems. A senior-year limnology class sparked her interest–and career–in water quality.

Sampling Water Around the State

Before the swim season starts, the Water Quality Unit travels the state, training the staff who will be responsible for sampling their beaches for bacteria and detecting harmful algae blooms, commonly known as HABs. Excessive bacteria and HABs are the primary causes of unsafe swimming conditions and leading to health advisories or beach closings. The team meets with park managers, lifeguards, and maintenance personnel across the state to explain the proper water sampling procedure, show them how to identify a suspected HAB, and teach them the reporting protocols. Each staff member identifies this as one of their favorite parts of the job.

“It’s great seeing the people you often coordinate with in person, putting names to faces,” said Lauren Gallagher, Aquatic Recreation and Health Specialist. Lauren has been with Parks since graduating in 2020 with a BS in Environmental Science from Siena College. She began her career as a summer assistant in the unit and has since moved to a full-time role.

State Parks staff collected 1,538 samples during the 2023 swim season.

Before the beaches open for the season, they are each sampled twice. Once the season gets underway, the beaches report their weekly data to Gallagher and the rest of the Water Quality Unit. The unit then works closely with the New York State Departments of Health (NYSDOH) and Environmental Conservation to record and report the data, collating it with weather conditions for research purposes to give a fuller picture of the state’s water health.

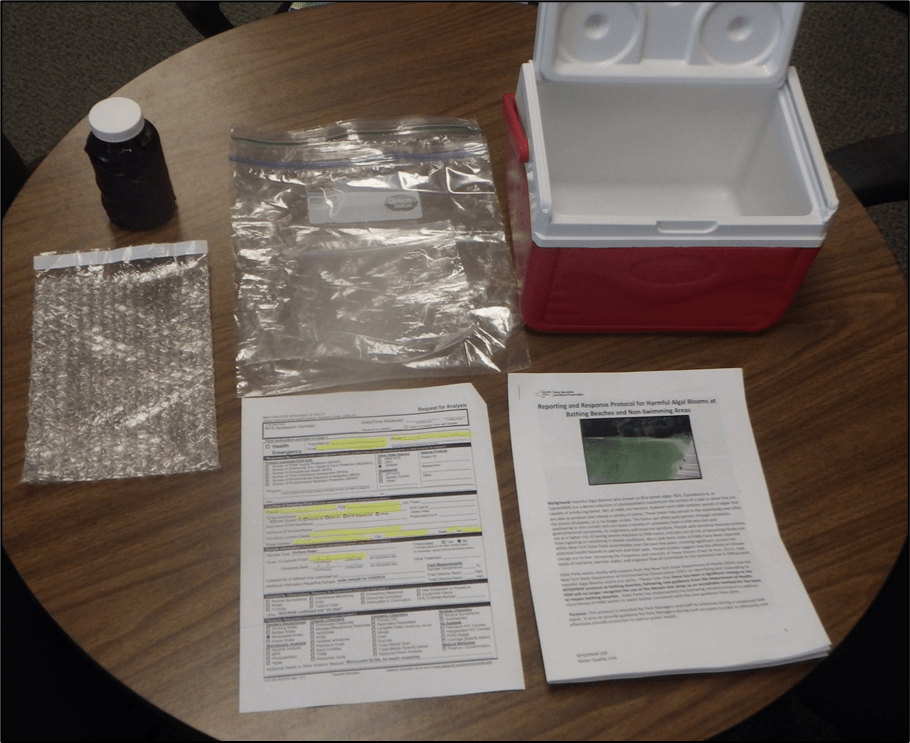

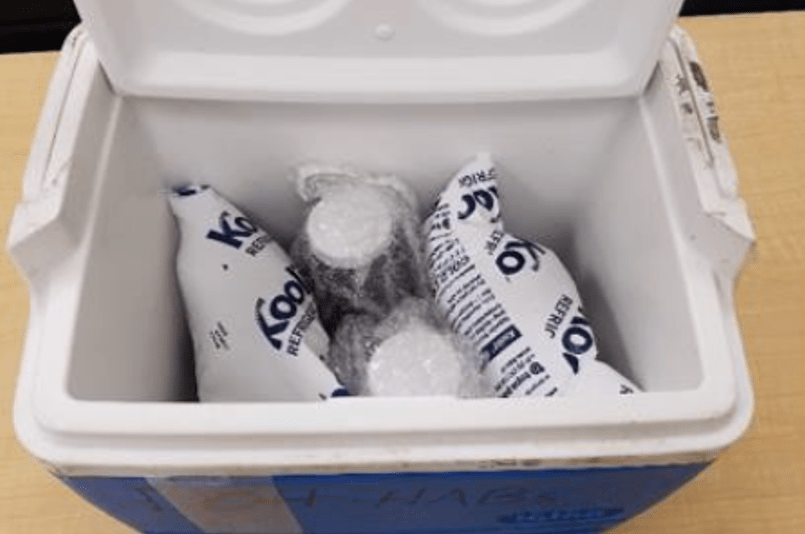

State Parks beaches test for bacteria at least once a week, usually on Mondays or Tuesdays. The designated staff member dons personal protective equipment and takes a sample. A large beach may have several sampling stations. The sample-taker records detailed information about the water level, clarity, color, odor, presence or absence of algae and shoreline debris, and nearby wildlife on a field sheet, as well as the time, date, and full description of the weather. The sample is brought to a government-run or private lab in a cooler to ensure the accuracy of the test. State Parks staff collected 1,538 samples during the 2023 swim season.

Visitation and Swimming Impacts

Beaches can be sampled whenever there’s a concern, and park managers get to know the conditions that might cause E. coli bacteria to rise to unsafe levels. It’s usually heavy rainfall, waterfowl feces, or agricultural runoff that causes what the team terms an “exceedance.”

Test results take roughly 24 hours and are reported to the Water Quality Unit and logged on a statewide beach status map. Park managers follow a flowchart to determine whether to open the beach as usual, open with an advisory, or close the beach altogether. Beach closures are publicized through the individual park web pages, through push notifications on the Parks Explorer App, and in some cases, through the park’s social media pages.

HABs: Safety First

The consequences of swimming in water with excess bacteria are unpleasant. Children and immunosuppressed people are most at risk for so-called recreational water illnesses, which include gastrointestinal trouble, respiratory difficulties, and skin irritation. But the consequences of swimming in waterbodies impacted by HABs are potentially worse, with possible long-term effects including liver and kidney damage and even degenerative brain disorders. Pets are especially vulnerable to negative health effects and could even die.

“Much more goes into water quality than just bacteria sampling,” said Lauren Badinger, who recently graduated from college and is working as a seasonal assistant in the unit. Originally interested in the social science aspect of environmental work, Badinger fell in love with fieldwork and has since gravitated towards the physical science aspect. She and the rest of the team noticed an increase in public awareness about HABs, as well as an increase in the number of HABs reported over the years.

In 2023, 279 swimming days were lost due to water quality issues at our beaches, 109 of them due to HABs.

The procedure for detecting HABs is more involved than routine bacteria sampling. The Water Quality Unit trains staff on how to recognize HABs, how to tell a HAB from excess pollen or from other aquatic vegetation blooms, and what to do if a HAB is suspected. When a HAB is confirmed, parks staff respond by posting signage, closing the beach (if effected) and monitoring the area. Once the HAB has cleared, the water is tested by specialized labs (only four in the state) to confirm conditions are safe for reopening the beach.

The cyanobacteria that cause HABs is diverse, ancient, and naturally occurring in every environment. Environmental professionals believe that human development and climate change have combined in recent years to create more favorable conditions for HABs. In 2023, 279 swimming days were lost due to water quality issues at our beaches, 109 of them due to HABs. Some HABs clear in a matter of days. Others are more persistent and can last for the entire season.

There’s nothing that can be done to make a HAB immediately go away. But by tracking data and comparing it to park conditions and to data collected by others, the Water Quality Unit is contributing to an effort to better understand and possibly prevent HABs. After the swim season ends, the team’s work on reporting, planning, and education goes into overdrive.

Sarah Moss is an Aquatic Ecosystem Biologist in the unit. Originally interested in environmental law, she shifted her focus and earned an MS in biology. Moss not only has a hand in the water quality testing, but studies how water quality affects the flora and fauna that call our waters home. Working with regional stewardship teams, she carries out waterbody and aquatic ecosystem monitoring throughout New York’s state parks. Recent projects include vegetation surveys and water quality sampling for turtle habitat restoration.

As one of the longest-serving members of the team, Moss sees awareness growing about the importance of protecting our waterways and improving water quality, not only for recreation by humans, but for the plants and animals with whom we share the planet.

“There is a growing interest in restoring our waterbodies and aquatic ecosystems (streams, wetlands, rivers, lakes),” she said.

“I’ve also noticed that people are becoming more open to learning about how global climate change can impact our natural resources. Many people ask how can water quality improve/how is this achieved, and how can we as a society to make it a priority.”

– Written by Kate Jenkins, Public Affairs Digital Specialist

For the curious and the rest of us, Please tell us what they test for, how they determine what to test, how frequently they test and what are comparisons with other municipalities. Thank you.

Thanks so much for your interest! A lot of the info is available in the post, but a quick answer: they test weekly for e. Coli bacteria and may test more often when there’s a concern (often, heavy rainfall will increase e. Coli in our lakes and rivers). Our staff is also on the lookout for harmful algal blooms. They’ll see the bloom growing on the water, close the beach, and get it tested by a lab. They then monitor it closely and re-test when the bloom seems to have died. The practices of other municipalities are outside the scope of the post, but most that manage beaches also have a system of testing for water quality to ensure safety. Thanks very much for your interest, and happy swimming!