What’s your first feeling when you hear the word moth: irritation or wonder? Anyone who’s gotten an unpleasant surprise when taking winter wools out of storage will agree that moths can be a menace to clothing and bedding. But at the same time, the varied species of moths lend beauty and majesty to nights outdoors and play an important role in our ecosystem.

As a textile conservator, Sarah Stevens works with historic site staff to prevent moth damage and respond to it when it occurs. As a wildlife biologist, Kelsey Ruffino facilitates the study of the moth population in New York State parks and ensures it has the support that they need to thrive. Both share their professional perspectives on these winged insects.

Historic Textiles vs. the Clothing Moth

There is one moth that feeds on historic textiles – the aptly named ‘Clothing’ or ‘Clothes’ moth. It mainly eats proteins like silk, wool and furs, so preservation folks are always on the lookout for these small, gold, flying beasts.

The first, best way to keep an eye on things is to open closets, look under bedding and shine light in places that are usually dark since that’s where the moths like to hang out. Keeping historic spaces dry and cool is also a good way to keep these pests at bay. They like dark, warm and humid spots best.

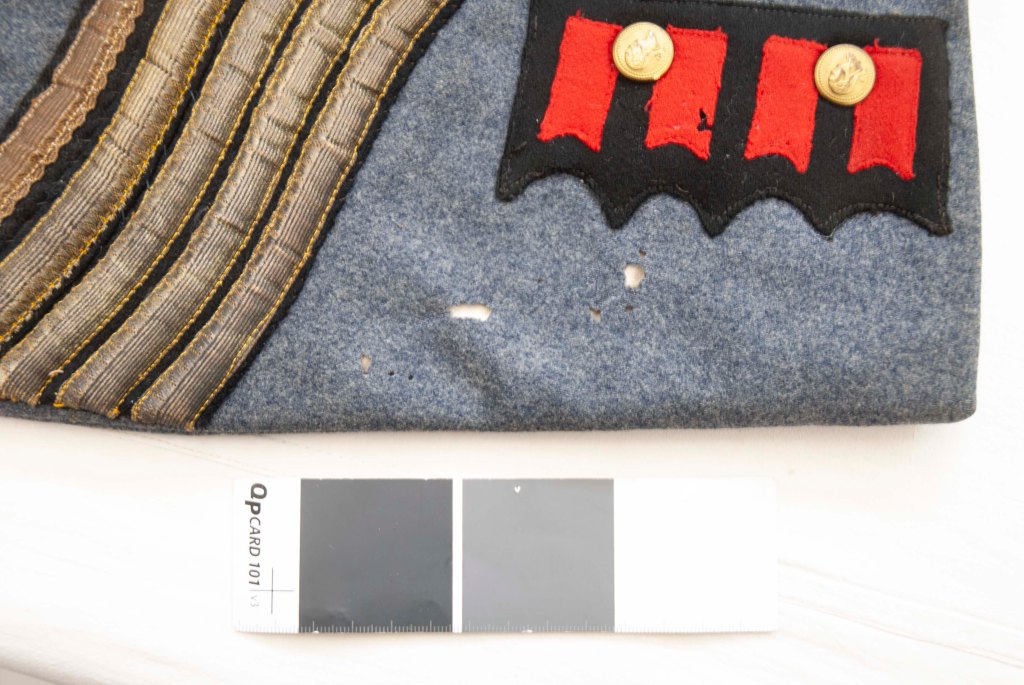

But what happens if you find one, or more likely, some? Try to find what they are feeding on and isolate it from the rest of the collections. They might be in more than one spot and eating more than one thing, so this usually takes a bit of time. You can tell what they have fed on, since there will be holes with even edges and likely some ‘frass’ left around.

Then, the item gets vacuumed with our low-suction vacuums, bagged and sealed, and placed in a chest freezer that will get cold enough to kill anything left behind like larvae. The items stay in the freezer for a few days, come out to thaw and then get put in again to make sure the beasts are really dead. Then we can assess the damage, vacuum the piece again and see if we need to stabilize it.

We also put out traps to catch as many moths as possible so they can’t wander around and lay more eggs.

Many of our sites have an Integrated Pest Management system, since moths aren’t the only pest issue – we’ve got all sorts of beetles to look out for, and mouse season is in full swing. If our sites find something and need assistance, they contact us at Peebles Island, and conservators all lend a hand to sort out the problem.

I’m headed off to put a few rugs back in the freezer!

Resources:

The ABCs of Collections Care, Greater Hudson Heritage Network

Museumpests.net

— Written by Sarah Stevens, Textile Conservator

The Wondrous World of Moths

It is true, some pesky, pest-y moths may feed on woolen clothes or stored grains, but most caterpillars eat plants outdoors. While Historic Preservation staff are out hunting down the clothing moth to protect historic textiles, Environmental Stewardship staff may be out surveying for rare species of moths to better understand the moth’s biology and protect their habitats.

Butterflies and moths are an incredibly diverse group of insects. Their classification order Lepidoptera (meaning scale-winged in Greek) is the second-largest of the approximately 30 insect orders, second only to beetles, which claim the highest diversity of insects. There are around 170,000 known species of butterflies and moths worldwide, and moths account for over 90 percent of those species. In New York State, there are over 1,000 species of moths, from the stunning green luna moth to the oh-so-familiar Isabella tiger moth (not so familiar? you may know it better as a woolly bear caterpillar!).

Our state parks are home to hundreds of species of moths with robust populations. Recently, moth expert Dr. Hugh McGuinness of the National Museum of Natural History partnered with the New York Natural Heritage Program to conduct an in-depth moth survey at Heckscher State Park on Long Island. By placing black-light traps around the park, Dr. McGuinness was able to examine more than 12,600 individual moths! He identified over 700 moth species, 18 of which were considered rare in New York and five of which were previously unknown here.

Moths, both as caterpillars and winged adults, are a critical part of the food web, particularly for birds and bats. Researcher Dr. Doug Tallamy estimates that it may take as many as 9,000 caterpillars for one pair of Carolina chickadees to successfully raise one nest of young! And though they are often overlooked, moths are also important pollinators. New research indicates that moths may be more efficient pollinators than bees and other day-flying insects.

If you would like to learn more about moths, or need help identifying a cool moth you’ve found, check out the citizen science website iNaturalist. To discover butterflies, moths, and the native plants they rely on as host during their caterpillar stage, specifically for your area, explore this Native Plant Finder from the National Wildlife Federation, based on Dr. Tallamy’s scientific research. Enter your zip code to find the best native species to attract and support the butterflies, moths, and birds in your area.

— Written by Kelsey Ruffino, Wildlife Biologist