As we New Yorkers endure the COVID-19 pandemic, the natural question for historians is: how did people react to epidemics in the past?

By now you may be aware of the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed tens of millions of people worldwide. Could the number of deaths have been lower if they knew back then what we know now? Did they practice social distancing? Close businesses? Shut down schools? Limit transportation and government services? Cancel public gatherings? Put people in isolation? Create temporary hospitals? Make people wear masks?

Spoiler alert…they did all those things. Reading about the steps people and governments took to limit the spread of the pandemic a century ago would feel shockingly familiar to us today. Our forbearers knew to do these things because the 1918 pandemic wasn’t the first to hit New York – not by a proverbial long shot.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, a form of social distancing was the norm in times of pandemics. When Yellow Fever ravaged the northeastern United States beginning in the 1790s, residents of large cities like Philadelphia and New York fled dense urban areas for the countryside, if they had the economic means to do so. The same held true in scattered outbreaks of the flu in New York in the 1820s, and when a large pandemic hit in the early 1830s.

There was, however, one particular influenza outbreak in 1872 that was so widespread, and so contagious, that no one in America could escape its effects. The 1872 outbreak crippled the economy, crashed every transportation network in New York State (steamboats, railroads, canals, streetcars), led to permanent changes in the Americans’ lives, and likely was one of the causes of the Great Depression – the Panic of 1873, which was called the “Great Depression” until the even-Greater Depression hit in the 1930s.

It was so bad that people were worried the 1872 Presidential election would be impacted by people’s inability to get to the polls (sound familiar?). For months, the disease was front page news on every paper in the country, but for all its devastating effects, the massive influenza outbreak of 1872 is hardly known or remembered today: it doesn’t even have its own Wikipedia page! To be fair, though, it also didn’t kill a single person…

The 1872 influenza outbreak wasn’t a pandemic, or even an epidemic, it was an epizootic (or more properly classified as a panzootic), an outbreak of a highly communicable strain of equine influenza. It was a horse flu.

It started innocuously enough in the fall of 1872 with small reports about horse-drawn streetcars in Toronto being shut down due to the so-called “Canada Horse Disease.” Theses blurbs about the disease were buried on the back pages of several New York newspapers, and everyone seemed wholly unprepared for what was coming their way.

On October 21, the “Canada Horse Disease” hit Buffalo and in a matter of days, all of canal country was full of sick horses. Thousands of horses and mules worked the Erie Canal and shared stables, and they sent the contagious disease in every direction along the state’s watery superhighways.

By Halloween, every equine engine in New York State effectively stopped working at the same time. It was no longer the back-page “Canada Horse Disease,” it was the front-page “Great Epizootic of 1872.” Although most horses and mules ultimately recovered, the only cure was rest. A resting horse could not work, and without horses, industrial America was unable to function. Why was it so devastating? Why were there so many horses?

If I asked you to picture a person and a horse in the late 19th century, you might think of this:

Or perhaps genteel Victorians on carriages:

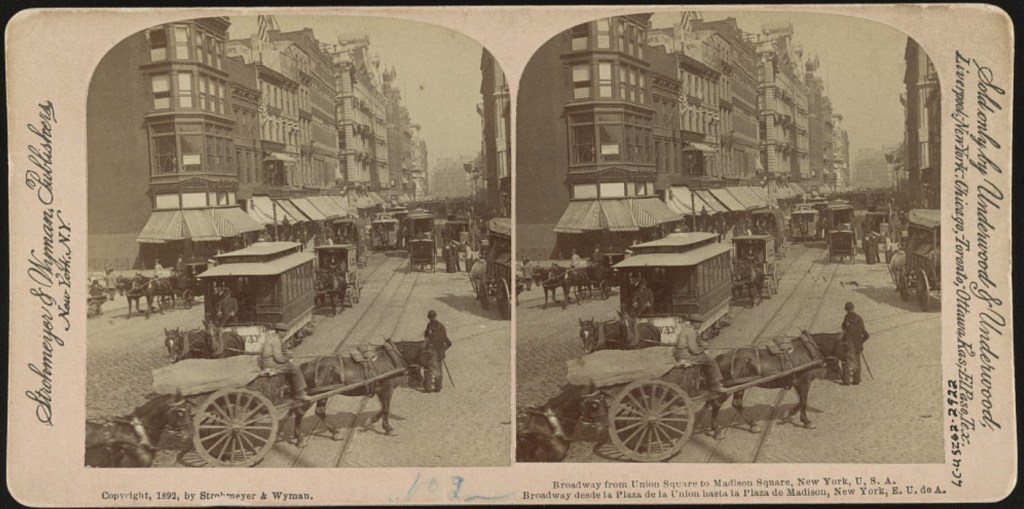

You might not picture this:

Post-Civil War America is commonly thought of as a time of rapid industrialization and mechanization, but in reality, horses and mules were still at the heart of every transportation system in the country and powered every aspect of life: they hauled people, freight, omnibuses (taxis) streetcars, fire engines, cavalrymen, carriages, canal boats, wagons, and anything else that needed to move. There were no cars, buses, trucks, subways, or motorcycles. There were horses, horses, and more horses on congested city streets.

Those cowboys pictured roping a buffalo on the plains might see ten or even twenty horses in a day. New York City and Brooklyn (a separate city until the 1890s) had a combined horse population of somewhere between 150,000 and 175,000 horses, and most were attacked by the horse flu.

On October 25th, the Utica Daily Observer reported 28,000 sick horses in New York City. Three days later, the Daily Saratogian reported that 7,000 horses in the city were stricken in a 24-hour period. In the end, the infection rate was around 90 percent. The horse flu impacted every aspect of American’s lives.

Grocers couldn’t deliver food.

Streetcars stopped running, stranding suburban commuters.

People couldn’t vote. The Buffalo Courier and Republic reported:

“There is considerable discussion in political circles, as to whether the sickness of so many horses through the country may not have an effect on the result in this and some other states by preventing country voters from getting to the polls on Tuesday, the [Presidential] election day.” Buffalo Courier and Republic Oct 31 1872.

Trains could run, of course, but what would they carry? Everything had to be delivered to depots by horse-drawn wagons, and when it arrived, it had to be distributed by more horse-drawn wagons. Railroads owned some of the largest fleets of horses in the 19th century. The same with steamboats:

“In the depots of the Erie, Morris and Essex and Pennsylvania railroads, a great quantity of freight is awaiting transportation, and the wharves of the large steamship lines are crowded with bales and boxes which cannot be moved.” Troy Daily Times October 26, 1872

The Buffalo Courier and Republic reported the same day that “of the 300 horses used along the New York City waterfront by stevedores, 280 have got the disease.” A short while later, the steamboats couldn’t move even if they wanted to—they had no fuel. The Hudson River steamboats counted on a steady supply of coal from Pennsylvania, but that entire operation relied on mules, who got sick and couldn’t work. Mules pulled carts from the depths of the mines and then other mules pulled freight boats of the coal on the Delaware & Hudson Canal up to river. By November, the Kingston Daily Freeman reported steamboat navigation was “nearly suspended” because of the lack of coal.

Eventually the Erie Canal—the economic lifeblood of New York State—was shut down. It would be like closing the Thruway today with all the economic shock that would create.

The November 9, 1872 edition of Albany Morning Express chronicled the economic impact: “It is estimated that the horse epidemic will affect canal trade to the extent of delaying each boat a round trip, equal to the movement of one and a half millions of bushels of grain from Buffalo to New York.” A typical boat made seven round trips per season on the canal, and boats weren’t running even before the canal officially closed, so most companies felt around a 20 percent revenue drop.

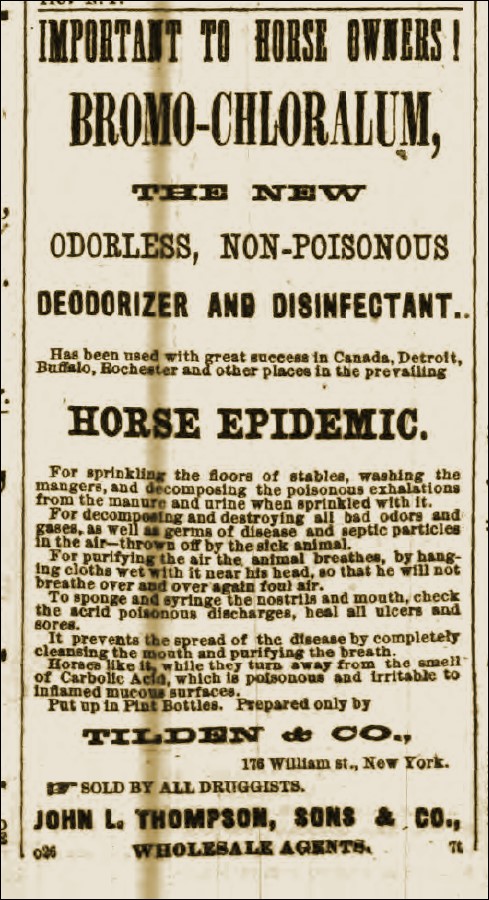

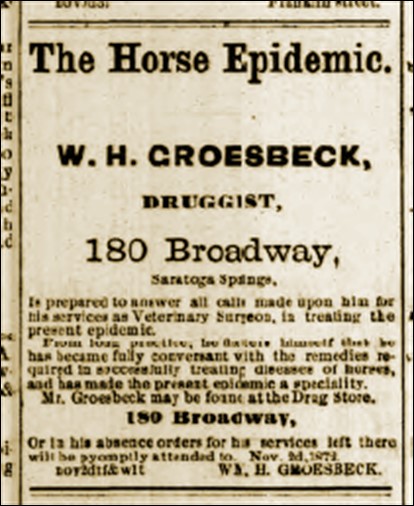

The lost revenue and lost work time bankrupted companies and farmers alike, but one sector of the economy boomed – cure alls. The late 19th century was a period of unrestrained and unregulated quack remedies. There was no federal Food & Drug Administration, and anyone could create a “patent medicine” and advertise it as cure for… well, anything.

Clark Stanley, the man who was literally known as the snake oil salesman, patented his now-infamous elixir only a few short years after the epizootic. Veterinary medicine was not well developed in America in 1872 – the first veterinary school in America closed in 1866, and another wouldn’t open until after the epizootic. Although experts appeared in newspapers advising rest and fresh air were the only cure, New Yorkers and others turned to quick fixes offered at the drugstores:

Pharmacies across the state offered a variety of “cures” for the horse flu.

In the end, humankind’s relationship with the horse seemed to be what suffered the most from the Great Epizootic. For thousands of years, humans depended on horses for everything, but as we climbed out of depths of the Great Epizootic and the subsequent financial Panic of 1873, technology would slowly replace the horse.

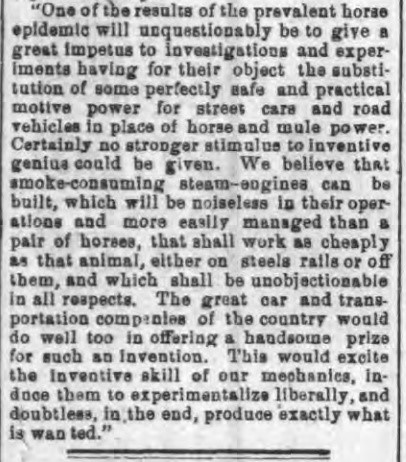

An editorial in the Troy Whig seemed prophetic in hindsight that horse power would be supplanted:

Or, maybe it’s better straight from the proverbial horse’s mouth. In this illustration from the Nov. 16, 1872 edition of Harper’s Magazine, a flu-ridden horse imagines better treatment by his human masters after his recovery:

Cover Photo- Horses pull a canal boat along the towpath on the Erie Canal near Utica. “Erie Canal in the Mohawk Valley” (No. 2635, Rochester News Co., Rochester, N.Y.)

Post by Travis Bowman, Historic Preservation Program Coordinator (Collections), Bureau of Historic Sites

Resources

After the outbreak, the U.S. Government commissioned a report into it by James Law, a faculty member of Cornell University, first dean of the New York State College of Veterinary Medicine, and a pioneer in veterinary medicine and public health in the United States.

Read his report here.

It is reigned not reined.

Actually … reined in is a term related to horses. Reins are straps attached to a horse’s bit, that are used to direct (and stop) the horse. So to “rein in” means to limit or pull back. Reign as a verb means to hold a royal office, as in a king or queen.

If the title were spoken, you couldn’t really tell which one it is because either one fits the context. You have to restructure the title to use either one unambiguously. A bit unusual to see a sentence like that – uniquely crafted!

We were striving for a headline that would make the reader think a little bit. Glad that it worked! And you are right: Either spelling works.

The flu was not “limited or pulled back”, it ruled, so to speak…if the story was about horse flu it would be a good pun…

You maybe should fix it.

You wouldn’t say a rein of terror, you’d say a reign…or you can reign as heavyweight boxing champion…it does not have to apply strictly to royalty.

Oops I read further and see it IS about horse flu LOL Good job! 🙂 And my bad! 🙂

That was my first response to seeing the verb. But upon reflection after reading the article, I realized that the state’s activities were indeed reined in because of the horse flu. Just as life today is reined in by the novel corona virus. Good word choice!

Great article! Thank you.

An amazing article! Thank you for presenting this information to everyone!

An excellent article. Well researched, written, and illustrated.

Durhamville is the location of the Mule loading.

The largest building is the Feed Mill on left.

I believe the young man just over the Mule

Would be a “Hoogie” for the boat and travel

In front of the boat with the mules.

The picture shows South towards the City of Oneida.

Thanks for the Post.

Interesting Article,read it all. Students in all schools should read this, it is history then,compared to what we are going through now.

As a horse owner and a history lover, I found this article absolutely fascinating! Thank you so much.

Interesting that I have known of “epizooty” for quite some time. As a local municipal historian in rural NYS town, I read this word in a newspaper article (yes from the 1870’s) in an old scrapbook of clippings and wondered what it was. Research revealed it as horse flu but I did not realize how widespread and devastating it was until years later when I attended a talk about the Erie Canal. This is an excellent article. I will be archiving it in my resource file.

Every spring, we make appointments for our horse’s vaccines. This is the best sales pitch for flu vaccination I have ever read! Epidemics are now something every person knows a little bit about. Thanks Travis for bringing epizootics to light!

What a captivating historical account! It’s intriguing to learn about the impact of the flu pandemic on New York and the measures taken to mitigate its spread. As I read through the challenges faced during that time, I couldn’t help but wonder how a <a href=”https://centerlinedistribution.net/”>calm horse supplement</a> could have potentially eased the stress and anxiety for both horses and their caretakers. Incorporating such supplements into the daily routine of these hardworking animals could have provided them with the support they needed to navigate uncertain times with greater ease and comfort. Thank you for sharing this fascinating glimpse into history and prompting us to consider the well-being of our equine companions in times of adversity.