Like the first birdsong, the start of Major League Baseball is a sign of spring.

Baseball fans celebrate the start of the season every year, but there are two other “baseball holidays” circled on the calendar of fans everywhere at opposite ends the season: Jackie Robinson Day on April 15, and Roberto Clemente Day on September 15. Did you know that New York State Parks has connections to both?

Breaking Baseball’s Color Barrier at Bear Mountain State Park

In 1997, Major League Baseball took the unprecedented step of retiring Jackie Robinson’s number 42 across the entire league – except for one day a year. On every April 15, the number is everywhere as all MLB teams take the field and all players and managers wear 42 to commemorate the day that the “color barrier” was broken and remember the extraordinary man who broke it.

Since the end of the 1800s, Black players had been barred from Major League Baseball through an unspoken but stringently enforced agreement. Several unsuccessful attempts had been made to integrate the league , but by the 1940s, momentum started to swing. Black and left-wing press and political leaders were pressuring the league. A new commissioner supported integration. And Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey was determined to make it happen for a mix of reasons.

Rickey, a devout Methodist, believed that racial discrimination was morally wrong and was both haunted and galvanized by ugly incidents he’d witnessed. As a highly competitive businessman, Rickey was eager to inject top talent from the Negro Leagues and gain a winning edge. He also recognized that the first MLB team to integrate would win the loyalty of millions of Black fans.

Evidence has emerged in the last 25 years that Rickey originally planned to sign several Black athletes at once. But circumstances brought his plan to bear on one man alone: Jackie Robinson, a four-sport athlete in high school and at UCLA, and an Army veteran accustomed to working and playing sports in a predominately white environment.

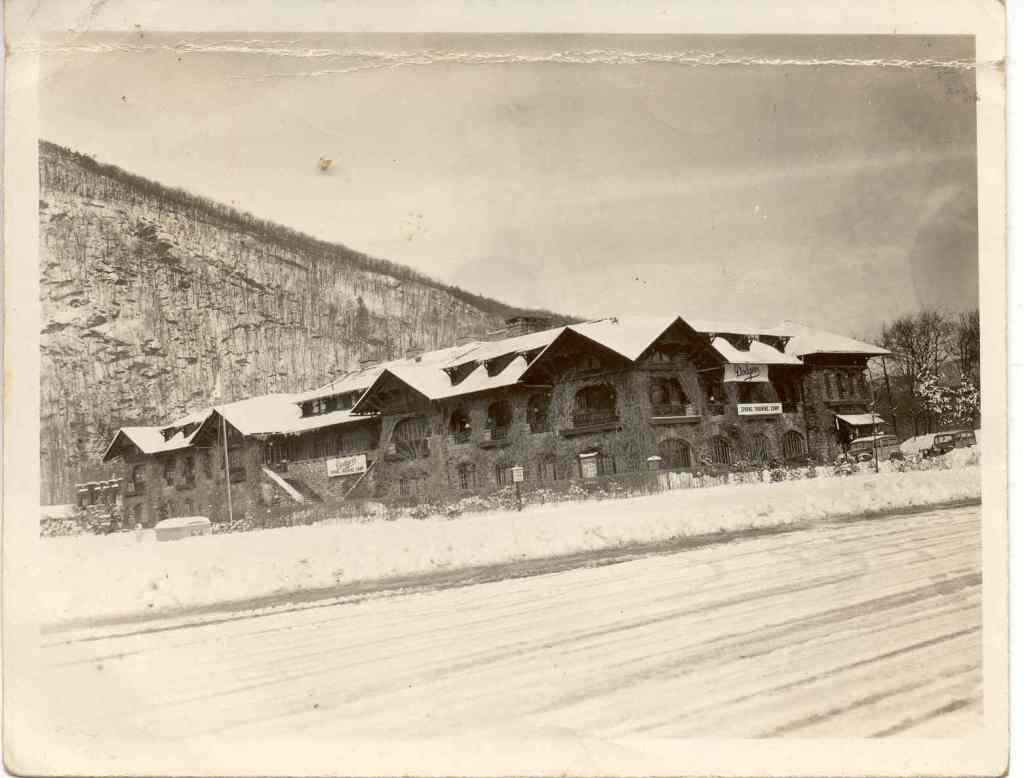

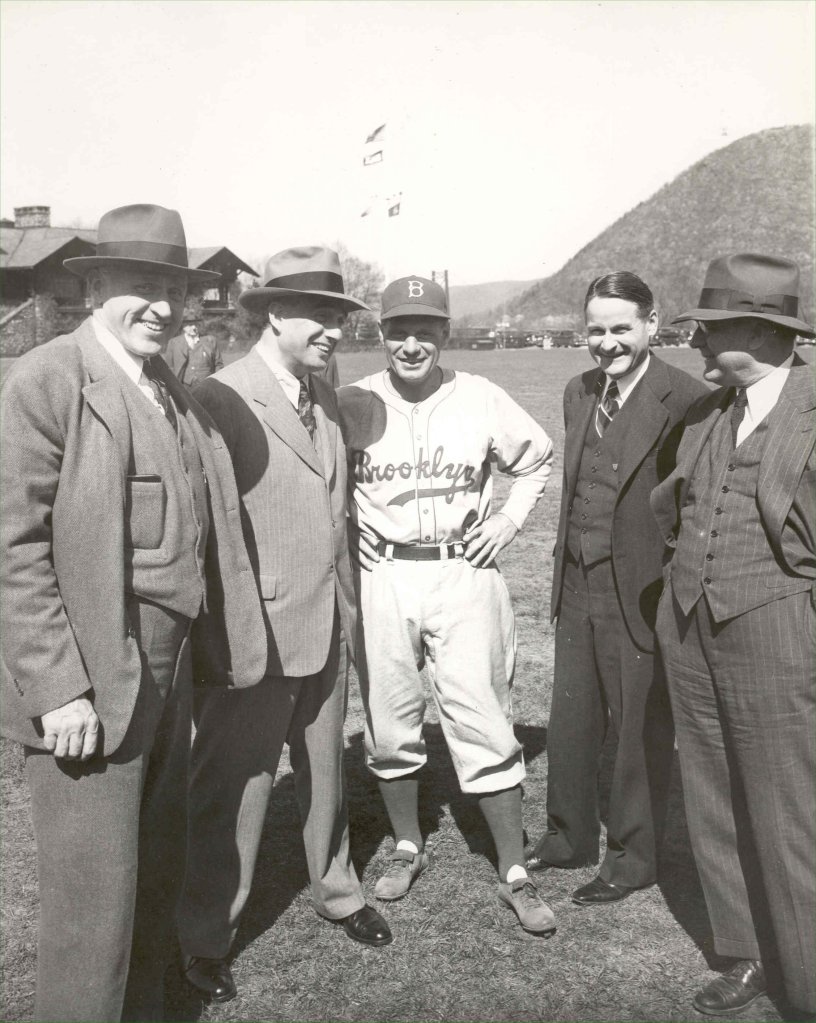

In 1945, Robinson traveled to Bear Mountain State Park to meet with Rickey. Due to wartime travel restrictions, the Dodgers were practicing at the park, as were other New York sports teams like the Knicks and the New York Giants football club (at the time, there was also a New York Giants baseball team).

Little is known about the details of this meeting that would transform baseball and advance racial equality in the United States. But he left Bear Mountain having inked a minor-league contract that had him and his wife Rachel Montreal-bound. In a preview of the history-making events that would come 362 days later, he took the field for the Montreal Royals on April 18, 1946, to a sold-out crowd dishing out both racist abuse and excited cheers for his athleticism. The Royals’ 1946 season still ranks in the Top 100 for minor-league teams, and the next year, Robinson made his major-league debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

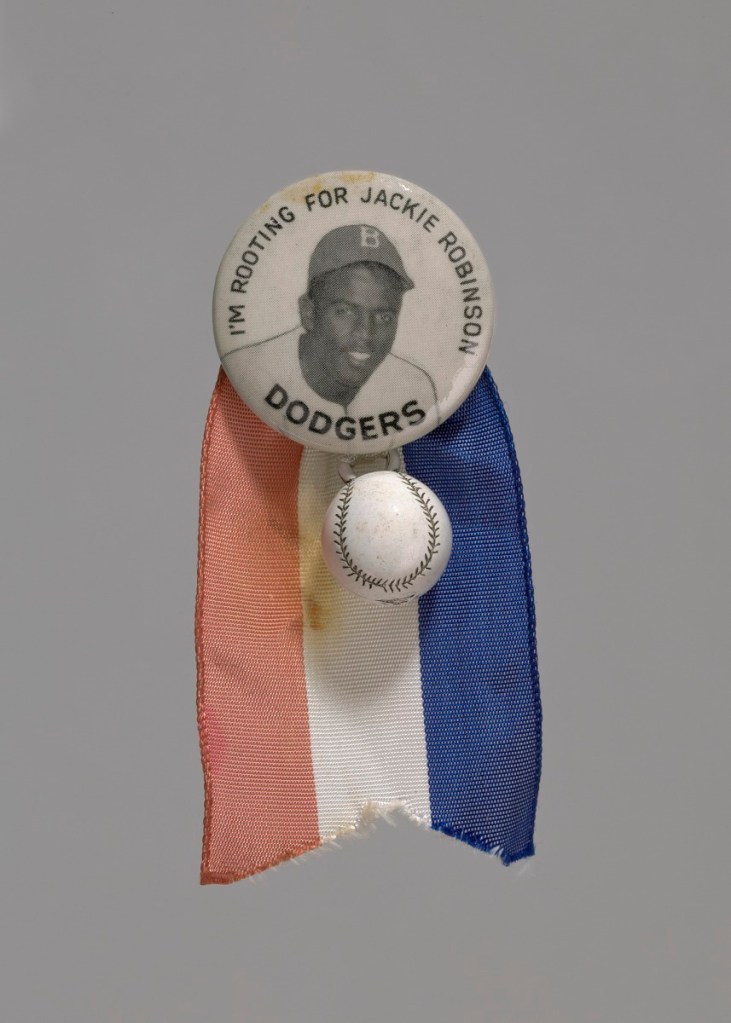

Rickey was right about Robinson’s appeal to Black fans. The Brooklyn Dodgers became Black America’s team, setting attendance records in nearly every National League city. A “Jackie Robinson Special” train ran from Norfolk, Virginia to Cincinnati when the team faced off against the Reds. Fans sported pins with Robinson’s image and the motto “I’m Rooting For Robinson.” Other teams began signing Black players.

But there was only one Jackie Robinson. His mental fortitude in the face of death threats, jeers, and all manner of dehumanizing treatment would be incredible enough, but he was also one of the best players in baseball history. His style of base running, with its emphasis on stealing bases, revolutionized gameplay. He won the 1947 Rookie of the Year Award (today known as the Jackie Robinson Award), 1949 National League MVP, and was an All-Star for six consecutive years from 1949 to 1954. In 1955, he won the World Series. Five years after his retirement, he was a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

Both baseball and America had – and have – a long way to go towards true equality for Black Americans and for all people who live in this country. But the signing of Jackie Robinson was a milestone in this long struggle, and it all started at Bear Mountain State Park.

A Legacy Of Service At Roberto Clemente State Park

Roberto Clemente Day is the other bookend to the MLB season. When all teams take the field on September 15, there’s a crispness to the air, the geese honk overhead, and the post-season fates of many teams (for better or for worse) are already sealed.

Roberto Clemente Day honors the day the Pittsburgh Pirates star recorded his 3,000th Major League hit – and, as fate would have it, his final game. It was the end of the 1972 regular season, and the Pirates had not reached the playoffs. Clemente’s hit made the game matter anyway. The crowd cheered, and the beloved Clemente raised his cap in recognition.

A little over three months later, an earthquake devastated Nicaragua. Clemente, renowned for his philanthropy, organized three relief flights, all of which were confiscated by the country’s government. Determined to get aid to those in need, he arranged a fourth flight which he would personally accompany. The plane crashed, and Clemente was dead at age 38. His legacies were not only of baseball greatness, but of philanthropy and of advocacy for Hispanic Americans.

“Roberto Clemente was to Latinos what Jackie Robinson was to Black baseball players. He spoke up for Latinos; he was the first one to speak out,” his close friend Spanish-language sportscaster Luis Mayoral once said.

Clemente was a 12-time Gold Glove award winner, the 1966 National League MVP, the 1971 World Series MVP, and a two-time World Series champion. He was so revered as a player and a person that the Baseball Hall of Fame waived its five-year waiting period and inducted him in 1973, making him the first Latin-American Hall of Famer.

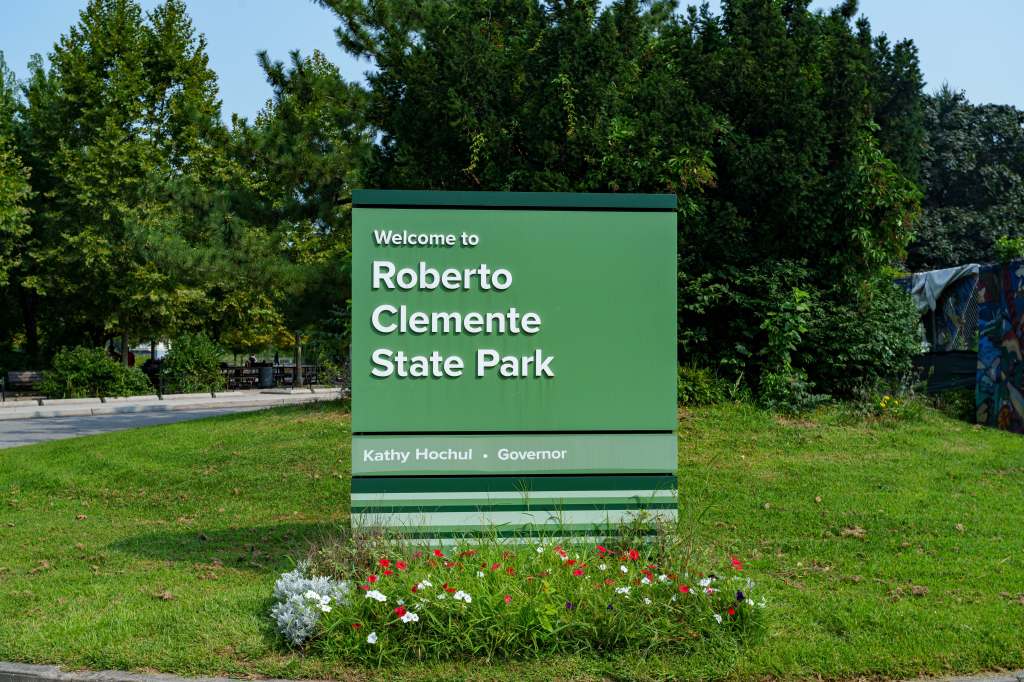

A less-verifiable but often-repeated honor attributed to Clemente is that he has more places named in his honor than any other professional athlete. One of those places is Roberto Clemente State Park in the Bronx, not far from Yankee Stadium. Originally called Harlem River State Park, it was renamed almost immediately in honor of the star and was the first New York State Park in New York City. And it’s keeping Clemente’s legacy alive in many ways.

“It was meant to be that I ended up at a park named after such a famous player,” said Acting Park Director John Doherty. “It’s an absolute honor.” A former Major Leaguer himself whose pitching career with the Detroit Tigers and Boston Red Sox ended with a 1994 injury, Doherty is passionate about serving the community through his park.

“[Roberto Clemente] would have a smile on his face if he knew about all the programming here,” Doherty said. A hidden gem off the Deegan Expressway, it hosts everything: adaptive physical education programs, t-ball, soccer, track, bocce, debate clubs, capoeira, and even a chess program. Monroe Community College and several adult leagues use their baseball fields, and the park participates in MLB’s Global Play Ball Weekend. Display cases inside the athletic complex house memorabilia from Clemente’s career, and his children have visited the park in the past as honored guests.

“Any time you have an opportunity to make a difference in this world and you don’t, then you are wasting your time on Earth,” Clemente once said. Doherty is determined not to waste a second of his, or of the park’s.

“It’s a safe haven for people in the summertime. People bring their kids, and they know they’ll be safe,” he said. “You are welcome at the park. We bend over backwards for you. We want you to leave with a smile on your face.”

— Written by Kate Jenkins, Digital Content Specialist, Albany Public Affairs