For eight years (1775-1783), the battles of the Revolutionary War crisscrossed New York. From the Canadian border to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, enslaved and free Blacks managed the shifting tides of the rebel’s fight against the British with mixed results. All of the changes did not come at one time, but eight years is wearing. Ultimately, Blacks living in the state paid a heavy toll.

Enslaved Africans in New York at the Start of the Revolutionary War

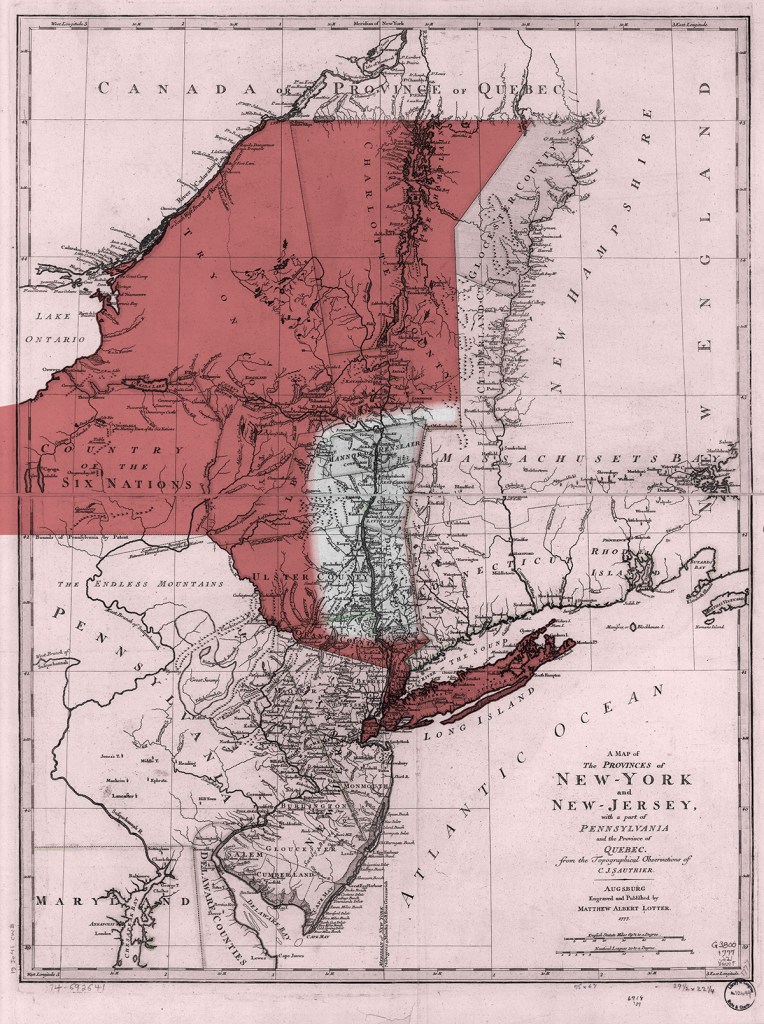

At the beginning of the war, the population of enslaved Africans and their descendants stretched across the colony and numbered more than 21,000 people. Even within the Country of the Six Nations, a few Blacks lived in isolated pockets. Although the common narrative places most of the population in the New York City area, only twenty percent lived there. Eighty percent of those enslaved lived outside of New York City’s limits. In Kingston, Albany, Troy and Schenectady, there were long-established urban Black communities predominantly made up of people enslaved within households. The rural wheat farming areas, which covered millions of acres (including Long Island and north of Kingston) were also home to thousands.

Sauthier, Claude Joseph, and Matthäus Albrecht Lotter. A map of the provinces of New-York and New Jersey, with a part of Pennsylvania and the Province of Quebec. Augsburg, 1777. Map. Library of Congress.

A Call to Revolution?

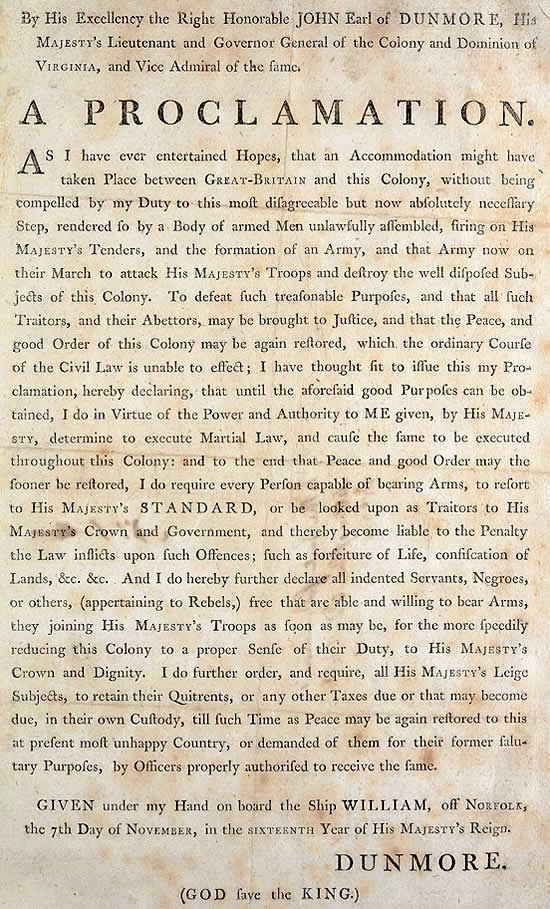

As the war moved across New York, Blacks in urban and rural areas responded in different ways. The Patriot language of liberty, including the Patriots’ desire to not be treated like slaves by the British, filled the air surrounding enslaved Blacks as they served in houses and on farms. But in the early years, as militias were gathered and trained, enslaved men were denied the right to serve. The American White leadership worried about slave rebellions if weapons were put into their hands. In contrast, the British issued the Dunmore and Philipsburg proclamations to the enslaved, enticing them to engage on the British side. More and more enslaved Blacks took up the call.

The Stories of Women and Children

Although the stories of Revolution include numerous accounts of Black men, the women and children caught in the chaos are missing from the narrative. In the early years of the war, most Black women in rural areas and smaller cities and towns remained where they were (like their White counterparts). For a single Black woman to self-emancipate and escape to British lines in New York City – often far from where she lived – the dangers were great. This was the case for most Blacks living above the mid-Hudson River Valley: many desired freedom, but few risked escaping.

Forced to Rebuild from Ashes

With towns and wheat fields burned by their owners or the armies, the work of the enslaved increased. Burnt wheat fields meant one army or the other had nothing to eat, but eventually the damage had to be cleared and the replanting and harvesting had to begin again. Towns like Kingston were burnt to the ground. Homes and businesses needed to be rebuilt. Following the burning of Clermont, just across the Hudson River from Kingston, historic records show that the men enslaved by the Livingstons sifted through the embers to find nails to reuse in rebuilding. Others did the same in Kingston. In some places, as Whites fled to safer locations, their enslaved Blacks were left behind to keep watch over the property.

Mohawk River Valley

Although fewer in number than other parts of the state, Blacks in the Mohawk River Valley found themselves both serving in the military or running for their lives with their enslavers. As Molly Brant, the Mohawk wife of Sir William Johnson, fled Johnson Hall to Canada, she took her enslaved women with her, as did other Loyalists living in the region. Following the Clinton-Sullivan campaign which burnt Indigenous villages in the Mohawk River Valley and further west, Mary Jemison, a White woman adopted into Native culture, took her children into the wilderness to live. They encountered a small farmstead run by two Black men. It is with them that the family recovered and remained for several years. Like all people living within the region, the enslaved and free Black populations had to bear the war and recover as best they could.

Black Entertainers During Wartime

The British stronghold of New York City had a large active Black community, where life was at times more normal than any of the other regions. It began with an established enslaved and free population which increased as people from New Jersey and points south made their way there. To lighten the drudgery of life in the cold months, dances and other forms of entertainment were commonly held, with music performed by Black fiddlers and drummers.

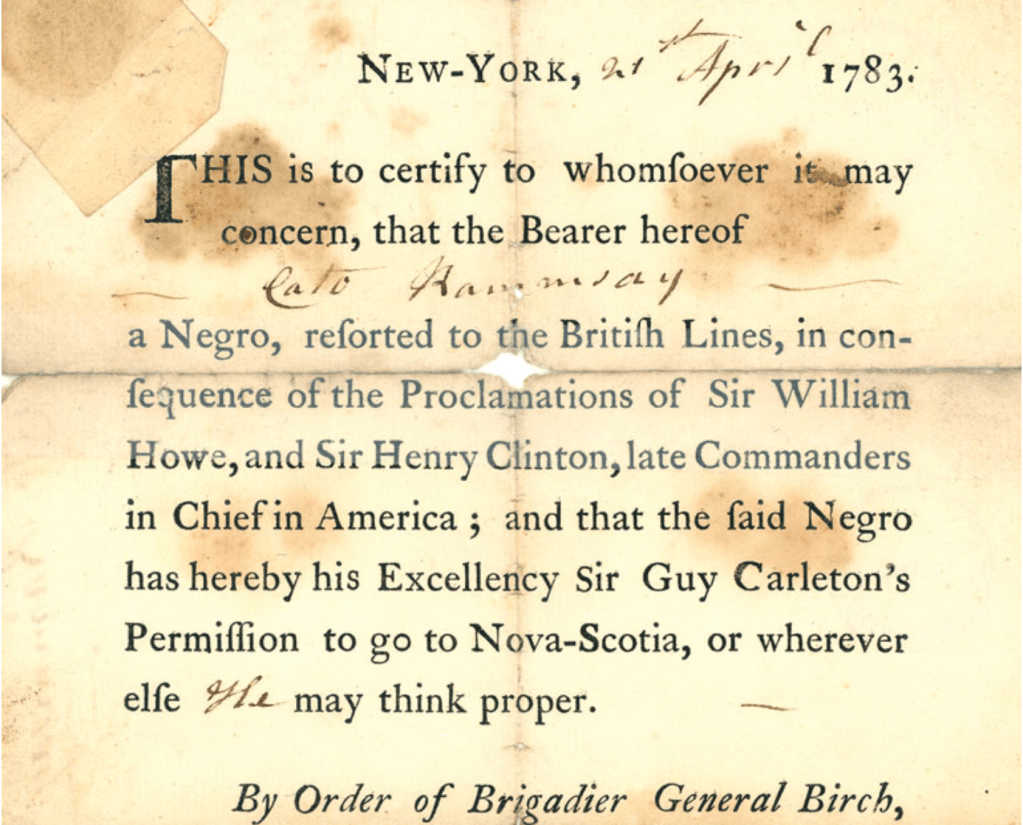

Freedom?

At the end of the war, thousands of formerly enslaved people left New York with the British, most bound for Nova Scotia. The Book of Negroes lists names from New York, but the majority leaving were southern freedom seekers. As they boarded the ships, others were not so fortunate and were returned to their enslavers. Black and White soldiers alike died on hospital ships, as smallpox and other diseases raged through the boats along New York’s coastline and further south. The Revolutionary War cut the ties that bound the American colonies to Britain, but not those between White enslavers and Black enslaved.

Ultimately, the enslavement of African descendants would continue in New York for 16 more years. Their labor was needed to rebuild the new state, even as manumission (people freeing their own property) was urged and talk of abolition (the legal end of slavery) bounced around in the new legislature. In 1799, the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery began the freedom process for children born after July 4, 1799. But it would take many other acts and 28 years before slavery in New York was outlawed. Even then, not all who were bound to servitude would be free.

—Written by Lavada Nahon, Interpreter of African American History