Is there a greater source of inspiration than nature? The natural world has inspired great works of art in every genre and style from cave paintings to classical sculpture, lyric poetry to hit movies, orchestral works to electronic soundscapes. Landscape architecture takes this process one step further, in which nature becomes the art. A landscape architect studies for years to learn the art, science and craft of working with plants and trees to make an artistic statement that complements both the natural surroundings and the architecture and meets the needs of their client.

New York State Parks and Historic Sites preserves many remarkable landscapes. As National Garden Week draws to a close, discover iconic landscapes at our historic sites and the fascinating stories behind them.

Planting Fields: An Olmstedian Vision Blooms

Planting Fields is a 409-acre historic site in Oyster Bay on the North Shore of Long Island. Located in an area often called the Gold Coast, the site was among hundreds of grand estates built in the late 1800s and early 1900s that reflected the emerging wealth sparked by the Industrial Revolution. While the fate of most of these estates was grim, Planting Fields survived with its acreage and historic structures intact. Today, more than 200,000 visitors enjoy Planting Fields every year. Its robust lineup of programs, including a spring and summer 5K, numerous cultural and seasonal festivals, and a thriving K-12 grade education program, activate the site year-round.

The name Planting Fields comes from the Matinecock, the Indigenous people of the land, who recognized and celebrated the area for its fertile soils. They named the area Planting Fields in their native tongue, honoring the land’s greatest attribute. The Coe family purchased the property in 1913 and called it home until W.R. Coe’s death in 1955, when the land was given to the people of the State of New York. Since then, Planting Fields Foundation, a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) created by Coe in 1952, and New York State Parks have worked together to steward this cultural and environmental asset.

The Olmsted Brothers were the successors to Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., the father of landscape architecture and the visionary behind New York City’s Central Park, the Buffalo park system, Niagara Falls State Park, and the Emerald Necklace in Boston, among others. A Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) completed in 2019 uncovered the full intent of the Olmsted Brothers’ vision for the designed landscape at Planting Fields and was the impetus for the recognition of their contributions. This set in motion an ambitious plan to revitalize and restore the landscape designs that were preserved in the Olmsted Archives in Brookline, Massachusetts. Since 2020, numerous landscape designs have been restored, largely made possible through private funding.

The Olmsted Brothers firm began working with the Coes in 1918 and continued until the late 1930s. Planting Fields has a layered history, with many contributors to its shaping. But the Olmsted Brothers left an indelible mark with their comprehensive approach to the various landscape features and their ability to create a cohesive and singular place. Included among these features are the Carshalton Gates entrance designed in 1921, with the historic eighteenth-century gates as a focal point for a sweeping and dramatic vista. In 1918, the Blue Pool Garden planting plan was developed, creating a private space surrounded by stunning plantings that would change with the seasons. The Heather Garden, restored in 2022 to commemorate the bicentennial of Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.’s birth, is a remarkable formal garden that offers a secluded experience nestled between the forest and lawn.

Both greenhouses were greatly expanded once the Olmsted Brothers became involved, so that they could not only house important plant collections, but also offer wonderful experiences for the Coes, their guests, and now all visitors to Planting Fields. The Olmsted Brothers transformed the Camellia House from a winter storage for a vulnerable collection to a full-fledged show palace. The iconic lawns, the Surprise Pool, the Vista Path, and many more such gardens are part of the Olmsted legacy at Planting Fields. Today, Planting Fields upholds the core Olmstedian value of parks as democratic spaces that exist for all people.

– Written by Gina Wouters, President and CEO of Planting Fields Foundation

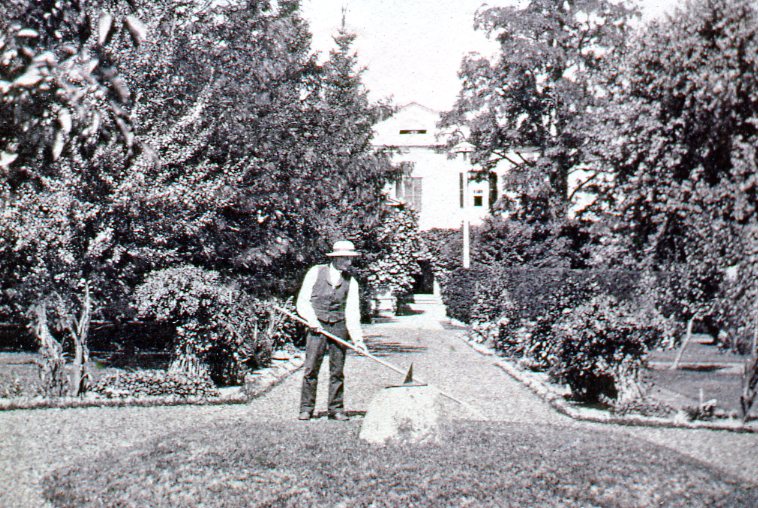

In Lorenzo State Historic Site’s Garden And Dark Aisle

For centuries, ornamental gardening was a popular upper-class pastime. But by the early 1800s, recreational gardening was fast becoming an integral part of life for all. In keeping with the prevailing idea that the glory of nature should be brought indoors, large homes often featured greenhouses, urban dwellings installed window boxes, and floral and plant motifs were popular for interior decorating. John Lincklaen’s original plan for his mansion, Lorenzo in Central New York, included a garden believed to have been laid out in eight parterres, or raised beds, planted with vegetables and flowers. Gravel paths ran crosswise between them, and a central path aligned with the house to create a visual extension of the main hall.

By the 1840s, American gardeners were attracted to the new Romantic Revival style of landscaping. Andrew Jackson Downing, landscape architect and major proponent of this style, favored visually linking a garden with the surrounding countryside. Lorenzo’s second owner, Ledyard Lincklaen, made many notations in his copies of Downing’s books as he slowly transformed the garden into a striking blend of old and new. Lincklaen first relocated the kitchen garden and changed the plantings in the parterres to grass, evergreens, and fruit trees to create a more Romantic design. Later, he removed the cross paths, installed a sundial as the focal point of the central path, and introduced narrow border beds along its edges, with peonies, iris, and day lilies.

In 1854, Ledyard Lincklaen began his lifelong project of creating the evergreen garden enclosure, today known as the Dark Aisle. It created both a visual break from the agricultural fields surrounding the house and a buffer from the prevailing west winds. He placed two markers, easily identified by his familiar “LL” monogram, to note the dates of his plantings which included white pines, Norway spruce, Canadian hemlock, and cedars. Following Lincklaen’s death, his wife, Helen Clarissa, continued adding to the enclosure. In 1867, she opened the paths we walk today.

Third owner Helen Fairchild retained much of her father’s design in the garden and grounds. During this period, Lorenzo’s formal garden gained renown when it was featured in the April 1899 issue of Ladies Home Journal and a 1902 issue of Country Life in America. These articles describe the planting scheme along the central path, which included nasturtiums, asters, phlox, irises, and lilies. In 1914, Fairchild commissioned boundary-breaking landscape architect Ellen Biddle Shipman to develop new plans for these beds. Radcliffe-educated and heavily involved with the famed Cornish Art Colony, Shipman was prominent among this first generation of female landscape architects. In 1924, Fairchild and Shipman had the chance to incorporate a piece of family history into the designs at Lorenzo. Ledyard Lincklaen had installed several public horse troughs along Cazenovia roadsides in the 1850s. With the advent of the automobile, the town was removing them. Shipman and Fairchild acquired one and added it as a focal point at the south end of the garden path.

With support from The Friends of Lorenzo, the formal garden is restored and maintained based on Shipman’s design. Staff recently completed a two-year project to clear out and revitalize the Dark Aisle. In collaboration with the Syracuse Garden Club, new trees are planted each year to replace ones lost to time and storms. Lorenzo’s grounds are open to explore every day, dawn until dusk.

– Written by Jacqueline Roshia, Interpretive Programs Assistant

A Ramble in the Jay Estate Gardens

The newly revitalized and award-winning Jay Estate Gardens at Jay Heritage Center are an expansive, educational, green space where American history, sustainability, and diverse cultural narratives all converge in the most accessible, and visually powerful way possible.

Thanks to a unique public-private partnership between the non-profit Jay Heritage Center, New York State Parks and Westchester County, three garden “rooms” have been filled with a glorious palette of resilient and stunning shrubs, grasses and perennials selected by landscape architect Thomas Woltz of Nelson Byrd Woltz (NBW). NBW created a dynamic plan that highlights the cultural history of this site. QR signage enhances the visitor experience. Preservation of architectural features like dry-laid stone walls and paths in the gardens illuminate the daily lives of the varied inhabitants from jurist, peacemaker, and New York State Governor John Jay and his descendants, to the Valentine Family – enslaved and freed women and men of African descent known to have lived, worked, and been buried at the Jay property.

In Room One, historic ash and cinder paths were protected, and their location revealed to mark the daily footsteps of real people from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries. Visitors wend their way through clipped ilex (holly) raised beds and roses and pass vegetable beds which are tended today by a crew of more than 30 dedicated garden volunteers. On any given day, the beds are overflowing with fresh strawberries, garlic, chives, kale, herbs and other produce that is harvested every Thursday and donated to a local food pantry.

Room Two contains a large Japanese Maple that is a living reminder of the later residents of the Jay Estate, the Van Norden and Talcott Families. A breathtaking selection of perennials including lilacs, peonies and bluebeard plants surround a reflecting pool that is a serene addition to this sensory garden room.

Protecting the site’s natural heritage has been of paramount importance. Reinterpreting the outdoor spaces as classrooms, NBW replaced over a dozen invasive species with over 36 different native plants. Room Three boasts a “menu” of a la carte native plant choices suitable for any size backyard. The species selected are grouped in attractive palettes of three – all are drought resistant and require no pesticides. Woltz selected native plants that are colorful like liatris, richly textured like “rattlesnake master” and sturdy like swamp milkweed and ironweed. They are guaranteed to bring butterflies, bees, hummingbirds and even turtles to delight their owners. A companion meadow design by landscape architect Larry Weaner has also vastly increased the biodiversity of the gardens with the addition of native sedges and plants including little bluestem, mountain mint, and beardtongue.

The most breathtaking landscape feature in the Jay Estate Gardens is an almost 100-foot-long arbor covered in cascades of blush pink “New Dawn” climbing roses. The fragrance is positively heady. The roses bloom twice a year each June and September. The structure pays tribute to the ingenuity and talents of early American landscape architect Mary Rutherfurd Jay (1872 – 1953). The great-great granddaughter of John Jay, she grew up on the estate, eventually studying design and horticulture at MIT and Harvard’s Bussey Institute. Her ability to deftly adapt gardens to any soil, style, or size constrictions later became a signature of her work. Today, the home that inspired her career is reimagined as accessible parkland and a center for horticultural education and environmental stewardship.

– Written by Suzanne Clary, President, Jay Heritage Center

Tracing the Roots of Bayard Cutting Arboretum

Bayard Cutting Arboretum is a 691-acre New York state park situated along the Connetquot River on the south shore of Long Island. The former Westbrook estate of Mr. William Bayard Cutting, a hobby botanist and conifer enthusiast, holds a rich history of landscape design and botanical specimens dating back to the nineteenth century. Gifted to the Long Island State Park Commission in 1936 by the late Mrs. William Bayard Cutting and her daughter Olivia James, this vast land has served as an escape for all from the fast-paced outside world. Olivia James wrote that the arboretum “…shall serve to bring about a greater appreciation and understanding, on the part of both the general public and of those professionally concerned with landscape design of the value and importance of informal planting, and shall thus be an influence in preserving the amenities of our native landscape.”

The collections at Bayard Cutting Arboretum have been carefully planned throughout the years. The Arboretum features original designs from Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of landscape architecture. Horticultural development of the estate begun in 1886 under the design guidance of Olmsted and was nurtured by the Cuttings. Olmsted celebrated the coastal landscape with three man-made ponds planted with native shrubs and trees. Oak Park, the Westbrook Wall Garden, the Woodland Garden, and the Royce Rhododendron Garden are also influenced by his landscape design. Visitors can study and enjoy unique tree specimens in an informal yet curated landscape.

With the cooperation of Charles Sprague Sergeant, then director of Boston’s Arnold Arboretum, Mr. Cutting several years later began to plant his conifer collection. The Arboretum is most recognized by the rare and diverse conifer collections. Original conifers sourced by the Cutting family still exist today, some the largest in the region. Currently, the Arboretum is a Level 4 ArbNet Accredited Arboretum with more than 5,000 specimens in their database. Collections at Bayard Cutting Arboretum include Oak Park, Westbrook Wall Garden, Great Lawn, Holly Walk, New and Old Pinetum, Pinetum Extension, Royce Rhododendron Garden, Breezy Island, Woodland Garden, Conifer Garden, River Walk, and Community Supported Agriculture Farm.

– Written by Joy Arden, Landscape Curator at Bayard Cutting Arboretum