The story of New York State Parks and Historic Sites is not just one of properties, but of people. During our Centennial year, we introduced you to some of them. In this new series, we take our scrapbook of memories down from the shelf and open it to share their stories in more detail.

She was “the hand that lit a thousand campfires.” Distinctive and almost prim in her hat, starched shirt, knickers, spectacles, and close-cropped hair, she had a zest for life. That zest saw her take a toboggan run at 70 miles per hour, throw a birthday party for a dog, and befriend some of the era’s most powerful people. She combined a knack for building relationships, an insistence on the highest standards, and a deep belief in her mission to build her program into a powerhouse that touched hundreds of thousands of lives. She was Ruby Jolliffe, and her 28-year tenure as Group Camp Director in the Palisades region continues to leave an impression more than 75 years after her retirement.

Her role was singular. No training could have prepared her for it. But her background as a city dweller and academic is still surprising. Born in Montreal in 1882, Jolliffe studied modern languages at the University of Toronto, Bryn Mawr and the Institute of St. Germain in France. She served as associate professor of modern languages and assistant in the English department at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, and as head of the modern language department in the Centenary Collegiate Institute in New Jersey (now Centenary University) before her calling found her in 1912, at 30.

At the urging of a friend, she left the halls of academia to become a camping director for the YWCA in New Jersey, and ultimately an executive for the YWCA in New York. In these roles, she became acquainted with the leadership of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission. When their group camp director resigned over a pay dispute, Jolliffe (as she was often called by her friends and colleagues) was the top choice of General Manager William Welch. Brushing aside any skepticism over whether a woman could do the job, he hired her to helm the program that brought the Palisades Interstate Park Commission $12,154 in the 1920 season alone ($196,880 of buying power in August 2025).

The program Jolliffe oversaw as the first female executive in the Palisades began almost accidentally, but had come to be relied on by Hudson Valley, New York City and New Jersey residents. The 50 group camps in the region were occupied by outside organizations (such as the YWCA) who brought campers to the Palisades to introduce them to the outdoors, teach them about their environment, and in many cases, to feed them and provide them with summer housing. Jolliffe managed the relationships with these organizations, maintained cleanliness and order within the camps themselves, developed programs for the campers, and trained and hired staff. It’s a job that was part property manager, part educator, part ambassador, part diplomat, part supervisor, part executive, and perhaps, uniquely Ruby.

The camps were a reflection of a societal belief of the benefits of the outdoors to city residents, particularly children who were impoverished or in poor health. It lent a higher calling to the rough, unglamourous work. Some of the camps were only accessible on foot. None of them had electricity. Campers used rustic latrines rather than flush toilets.

But Jolliffe worked tirelessly to keep the camps up to the highest standards. In the summer months, she lived onsite in a cabin in Popolopen Gorge, returning to her New York City home for the winter. She patrolled the camps constantly. She hired a health inspector to ward off disease, a serious concern in an era before antibiotics and vaccines. She drew on her educational background to develop varied programming to engage the minds and bodies of the young campers. Under Jolliffe’s dedicated and capable leadership, the program grew to an astounding 102 group camps at its height before settling at 71 with a combined population of 6,400 – unequaled nationwide. And she did it with virtually no administrative support.

Writing in 1990, Tib Kelly Saunders, who worked for Jolliffe as a naturalist and became a friend, reflected:

“Today Jolliffe probably would have a large staff, separate administrators for rents, health codes, maintenance, each with a bevy of computers. Instead, she had one secretary… Alma Fleck, a loyal, capable, calm automaton. Just to follow Jolliffe around the back roads and keep track of her schedule was no small accomplishment. But the impressive part of all this was that with her talents and high ideals she made the job bigger than it need be. She created a model establishment, a super-super organization.”

Jolliffe’s staff and campers remember her as a leader who set high standards and inspired those around her to live up to them.

“During the forties, I was among the Girl Scouts of Camp Lochbrae (K-14) at Kanawauke, and I was among the ‘awed” when she came to dinner,” recalled Elizabeth Stalter, who played Jolliffe in a 1993 celebration of her work and era at Harriman State Park. “At that time, I didn’t know what her position was, but I and my campmates knew that hers was a presence not to be taken lightly. I DID know that everything in camp had to be maintained in ‘ship-shape.’ Miss Jolliffe might arrive un-announced at any time.”

Jolliffe was key in developing Bear Mountain State Park as a year-round destination. That 70-mile-per-hour toboggan run was on a ramp constructed under her suggestion. She co-founded the Bear Mountain Sports Association in 1922 to promote skating, skiing and snowshoeing, and other athletic activities that have come to define the park. She then served as its president for the rest of her career.

In collaboration with Trailside Museum Director William Carr, she established “regional museums” throughout Harriman State Park. His trained naturalists provided campers with unforgettable, up-close animal encounters. A famous technique was to allow a snake to casually crawl out of the presenter’s collar or shirt sleeve while they carried on with their talk, feigning obliviousness.

Jolliffe’s knack for building and nurturing connections defined her life and work. She was friendly with W. Averell Harriman, and persuaded him to allow her YWCA campers to spend the summer at his Arden estate when Camp Blauvelt was needed by the military during World War I. She counted Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt as friends and can be spotted in many of the photographs and film reels of their regular visits.

She also collaborated with a Chickasaw actress and storyteller known professionally as Princess Te Ata (legal name: Mary Frances Thompson Fisher) who performed frequently for the young campers, in addition to appearances on Broadway and for heads of state. Such was Te Ata’s importance that Jolliffe arranged for a lake created by the Civilian Conservation Corps to be named in Te Ata’s honor. Hundreds of campers attended the ceremony as Te Ata arrived on the lake in a canoe. Eleanor Roosevelt christened the lake by pouring waters collected from all the other lakes into the park into Lake Te Ata.

Saunders remembers the congenial atmosphere she fostered among the staff: “She convened staff meetings every week, sometimes at her cabin where she’d show off Skippy, her airdale, who would follow commands in French. She’d say, “Ouvre la porte,” and Skippy would nuzzle his nose in a crack in the door, and swing it open. Often we met in each other’s museums and this meant we spruced up, collected extra specimens, and ordered a chunk of ice from the nearby kitchen for lemonade. Sociability took a big priority and plans were made for later games of Michigan, using kitchen matches for chips, or discussing our Sunday staff hikes.”

Jolliffe knew how to have a good time, and was described by former Trailside Museum Director Jack Focht as “a curious mix of dignity and devil-may-care.” She was remembered for her famed toboggan run, for the time she took a spin on a police motorcycle and drove it into the wall, and for her general high spirits. Camp counselor Josephine Conklin recalled: “The best time I remember was going to her dog (Skippie) birthday party. I thought that was great. The funniest part was that several people thought it was Ruby’s birthday and their gift of silk stockings and flowers was really not appropriate for a dog — they thought ‘Skip’ was HER nick-name.”

Through this mix of personal qualities, she elevated the group camps to a high standard. Although she was exacting, she was also the kind of leader who inspired others, willing to roll with all punches and requiring nothing of her staff that she wasn’t willing to tackle herself. Her focus on service and unwavering support of her team made the hard work seem lighter. In his definitive history of the region, Palisides, Robert Binnewies wrote of Jolliffe: “[She] won allegiance for being fair and quietly charming, listening carefully, and when necessary, acting tough as nails…Children, awed by Jolliffe, would carry memories of her far into their adulthood. Welch…had a formidable colleague who saw no limitations to the good that could be accomplished in the parks.”

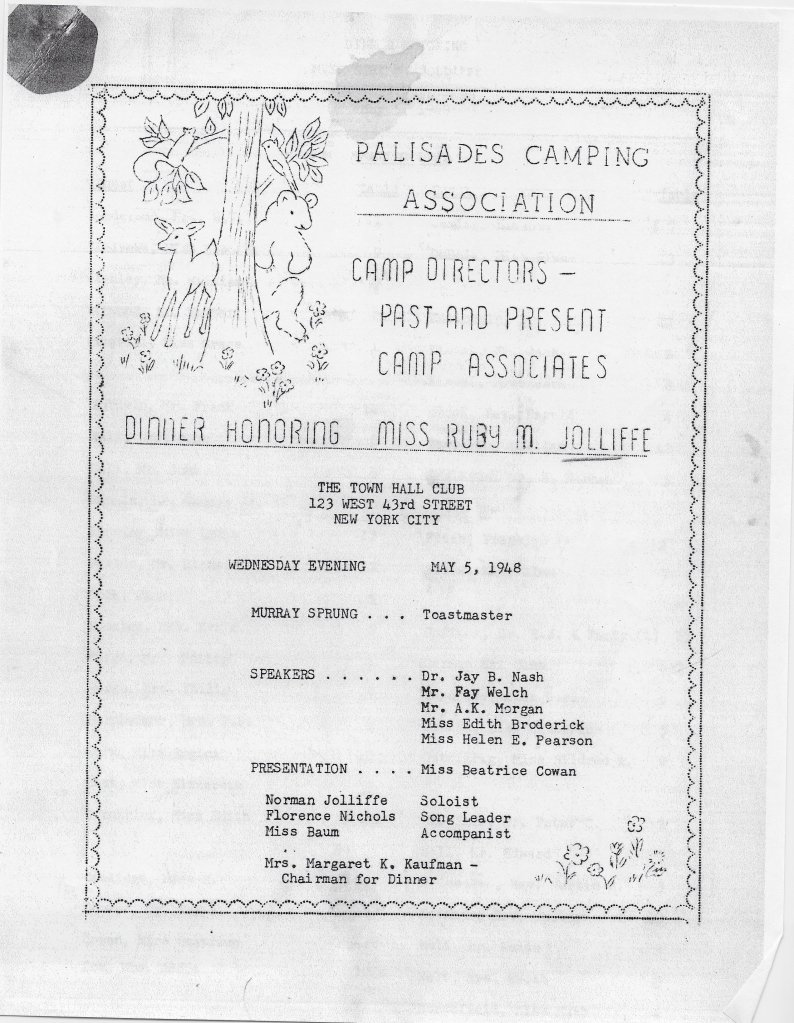

But nothing lasts forever. The 1940s brought leadership changes to the Palisades region, some due to politics, others due to personal circumstances. William Welch, who bucked convention to hire Jolliffe, died in 1941 shortly after being pushed out of his role by Robert Moses. William Carr’s ill health and personal turmoil led him to the milder climate of Arizona, where he became co-founder of the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. And Jolliffe herself announced her retirement in 1948. Her colleagues, staff, former campers and friends sent her off with a dinner party at The Town Hall Club in New York City full of song, memories, and inside jokes, marking the end of an era.

Jolliffe retired to North Carolina, where she lived for another 20 years, at one point taking a teaching job in Florida. In 1968, her longtime secretary, Alma Fleck, wrote back to Bear Mountain: “I am sorry to be the bearer of the sad tidings that our good friend, Ruby M. Jolliffe, passed away peacefully…[she] had been mentally alert, but very frail physically for about a year and at last the tired heart which had rallied so many times failed, so that death came as a friend.” Although Jolliffe had come to love North Carolina, she wished to be buried in the park where she spent so many deeply meaningful years. Fleck wrote further:

“On July 17 there was a brief service in St. John’s- in-the-Wilderness, the tiny chapel in the heart of the Palisades Interstate Park where Jolly had gone so often for hikers’ services. She was carried to her grave in St. John’s church-yard by members of her beloved Park patrol. It all seemed so fitting: camp children at play across the road; the green hills; the devoted friends, staff and former colleagues who gathered to be with Jolly as a testament of their love and esteem, and at the end, woodland birds breaking out in a final, joyful chorus. I think Jolly’s spirit must have rejoiced and been glad.”

—Written by Kate Jenkins, Digital Content Specialist. Thanks to Sue Scher, Palisades Group Camp Historian; Matthew Shook, Palisades Interstate Park Commission Chief of Staff; and Christopher O’Sullivan, Environmental Educator at Trailside Museums. All photographs and documents from the Palisades Interstate Park Commission archives unless otherwise noted.

This was a wonderful story. I love learning and reading about women of accomplishment who have made a difference in the world. They were unknown to the public and the world at large when I was growing up and even when I was in college. Girls and young women need to know there are an endless number of paths they can follow on their personal life journey.

Ruth Lewis

Homer, NY