The history and impact of the Erie Canal stretches back over 200 years, across more than 300 miles, and millions of lives. It is complicated, it is messy, it is multidimensional. You can become fascinated by it through the economics, the politics, the engineering, the social and cultural changes, the environmental impact, music, folktales, art, or a general love of history. Like the canal itself, history is a ribbon that connects us, for all the good and the bad.

The capstone of the revitalization of the Erie Canal during its Bicentennial is the inspiring journey of a replica canal barge. Buffalo Maritime Center enlisted the help of volunteers, donations and corporate sponsors to create a new version of The Seneca Chief. The original barge made the inaugural journey on the entirety of the canal in October of 1825, carrying Governor DeWitt Clinton and a keg of Lake Erie water. The replica Seneca Chief is on a similar journey in its path across New York State, but on a far larger, more complex journey through history.

The approach of the Erie Canal Bicentennial saw a renewed urgency to understand the legacy of the grand canal. Over the last eight years, celebrations and commemorations took place along the canalway. Between 2017 and now, Erie Canal communities held festivals, community cleanups, presentations, exhibits, and more to recognize the importance of the canal to their history. In 2017, Inland Waterways International held the World Canals Conference in Syracuse.

The New York State Museum presented the yearlong “Enterprising Waters” exhibit in Albany. The Albany Symphony Orchestra gave an innovative multi-year, multi-site series of performances inspired by the Erie Canal and its history. “On the Canals” adventures included free pedal, paddle, and arts programs. The Corning Museum of Glass barge journeyed across the state, as did Flotsam River Circus. The Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor and agencies such as the NY Power Authority, NYS Canal Corporation, and NYS Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation supported these and other unforgettable cultural experiences. Stewarts rebranded an ice cream flavor into “Minted in 1825.” Even the NY Lottery has a special Erie Canal Million ticket. Less splashy but more impactful are economic redevelopment grants to help canal communities revive their downtowns and public spaces.

Documentaries and learning materials produced by WCNY, WMHT, the Erie Canal Museum, and the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor have educated thousands of students – and the general public. And schoolchildren across the state enjoyed free field trips to canal locations across the state through the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor’s Ticket to Ride program and NYS Parks Connect Kids grant.

Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” This is also true of the Erie Canal and perspectives on its impact on New York State and America. Let’s take a look at how the canal has been viewed for centuries. But first, a crash course in its history.

Building the Erie Canal

Since the late 1600s, navigation on New York’s waterways fostered trade between Europeans and Indigenous peoples. With that trade came conflict and alliances that would shape global dynamics. By the late 1700s, when American colonies gained independence from Great Britain, folks took notice of New York’s geological advantage: the Mohawk River Valley.

When the New York State government reached out to then-President Thomas Jefferson for help in creating a canal along this route, he reportedly called it “little short of madness…” Undeterred, the state forged on, creating a canal commission and passing legislation to authorize the immense expense of the undertaking. A key advocate, New York City politician DeWitt Clinton, was elected governor in 1817. The State Legislature passed the Canal Act on April 15. By July 4, ground was broken outside of the village of Rome.

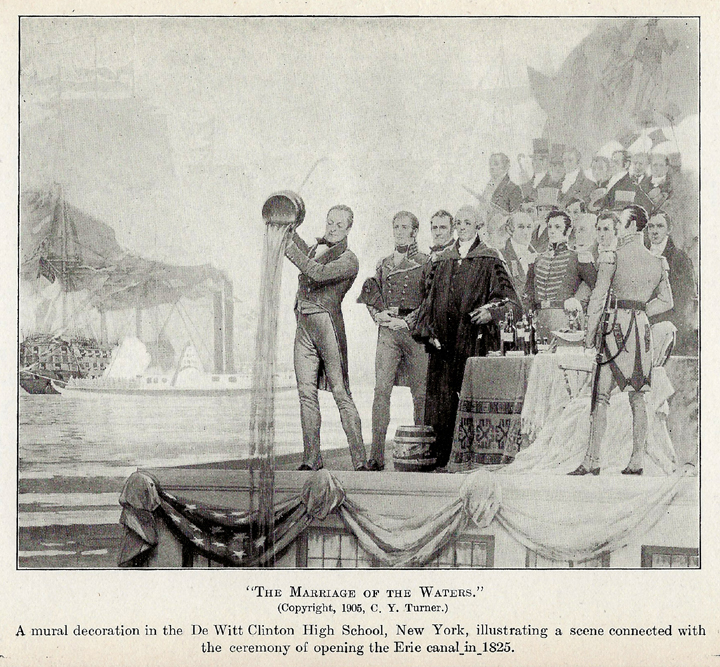

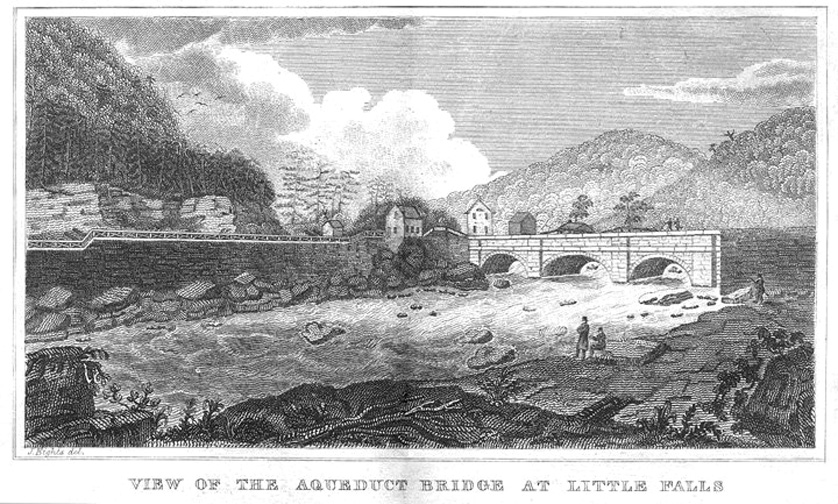

Construction began with a strategic move by lead engineers Benjamin Wright and James Geddes to tackle the simplest part first: a 90-mile section connecting Utica and Montezuma. This segment was finished in only three years, demonstrating the project’s feasibility. Next, construction crews, increasingly made up of immigrant laborers, faced the technically-demanding Eastern and Western Divisions. They overcame significant obstacles to create huge aqueducts and the monumental Lockport “Flight of Five” locks. The canal was finished in October 1825, with celebrations across the state culminating in Governor DeWitt Clinton’s symbolic “Wedding of the Waters,” which marked the union of the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean.

The canal had an immediate and enormous impact. The trip between Buffalo and New York City was shortened from one month to one week. Shipping costs were cut to one-tenth of their former price. This sparked a boom in trade between the Midwest and the Eastern seaboard, with New York City quickly becoming the nation’s leading port. Along the canal’s path, cities like Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, and Utica grew into transportation and industrial hubs.

Transportation to Recreation

But by the end of the 1800s, railroads began to outpace the canal. In response, New York built the Barge Canal System, completed in 1918, which “canalized” natural waterways like the Mohawk and Seneca Rivers. Though the canal remained a key commercial route until the 1959 opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, it gradually lost economic importance.

Rebuilt, rerouted and enlarged three times, New York still operates the Erie Canal today, which connects Albany to Buffalo and serves as a recreational route for boaters. Commercial cargo is more specialized and inconspicuous on today’s Erie Canal. The canal also produces hydroelectric power and provides irrigation for municipalities and businesses. In the Mohawk Valley, it mitigates storm impacts.

The Erie Canal continues to evolve beyond its heritage. While boating remains central to its identity, the historic Erie Canal is being revitalized by the NYS Canal Corporation, the NY Power Authority, NY’s Downtown Revitalization Initiative and many other organizations in communities along the corridor. A prime example of this renewal is the 2020 completion of the Empire State Trail, a multi-use path that parallels the canal and draws millions of visitors and millions of dollars in economic revenue each year. The Canal Corporation’s efforts include economic development for the 200 communities along the canal, environmental stewardship, and the promotion of arts and culture to carry on the canal’s 200-year-old legacy of connecting people and ideas.

So goes the usual narrative of the Erie Canal. And, while all of that is true, there is much more to the story.

Women’s Rights and Suffrage

The Erie Canal was a vital “waterway of change” for the women’s rights movement. The canal’s 1825 completion brought new ideas and people into Upstate New York. This influx fueled the religious and reformist fervor of the “Burned-over District,” where movements like abolitionism and temperance flourished. The women’s rights movement emerged directly from abolitionism, with activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott applying their skills to the cause of women’s suffrage. The canal connected regional activists for the groundbreaking 1848 Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls. Later, suffragists in the early 1900s held “Canal Boat Campaigns” to spread their message. The canal’s towpaths facilitated the adoption of innovations like “bloomers” and bicycles, which offered women new freedoms. As seen in the lives of women who worked on and alongside the boats, the canal’s progressive influence coexisted with the era’s traditional gender norms .

Haudenosaunee Displacement

For the Haudenosaunee, the canal represents a painful legacy of betrayal and devastation, not a symbol of triumph. The American Revolution and decades following it had a devastating effect on upstate New York and its Indigenous inhabitants. In the aftermath, with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy weakened, the United States used this “conquered” territory to pay its war veterans.

The canal was built directly through the homelands of nations like the Mohawk, Oneida, and Seneca. Its construction resulted in severe environmental and economic damage and the mass dispossession of their ancestral lands in New York. Through illegal treaties and land grabbing, New York enabled an influx of white settlers and facilitated “Indian removal” policies (their own as well as the Federal act of 1830), pushing Indigenous peoples onto smaller reservations or out of the state entirely. This displacement devastated traditional ways of life and connection to the land. Environmental damage from the canal, including rerouted watersheds and dammed streams, further contributed.

Anti-Slavery and the Underground Railroad

The Erie Canal played a pivotal role in the 1800s as a key route on the Underground Railroad, assisting enslaved individuals – who we can call freedom seekers and self-emancipators – in their journey to freedom, particularly to Canada, where slavery was abolished in 1834. Its network connected the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, establishing a path toward free Canadian territory.

Freedom seekers traveled the canal corridor by packet boats or towpaths, sometimes with financial assistance from abolitionists and sympathizers. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 made this route to Canada even more crucial, as it offered a path to safety from the law’s reach.

The canal corridor also became a center for the abolitionist movement, fostering anti-slavery sentiments and activities in towns along its route, especially after New York officially abolished slavery in 1827. Notable abolitionists like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass were active in the region, using the network of safe houses and helpers in cities like Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo to guide freedom seekers north.

An array of government agencies and non-profit organizations preserve the history of this route and the social reform movements that flourished along it. Sites like the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in Auburn, Stephen & Harriet Myers Residence (Underground Railroad Education Center), and the Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center tell the stories of those who traveled the canal in their quest for freedom.

Along the Erie Canal, movements for animal rights and social reforms emerged to protect children from devastating child labor practices. Ideas spread, germs spread, the water fed entrepreneurs to make millions, and drowned hundreds or more working-class laborers and community members in its operation.

This leads us back to the replica Seneca Chief and its modern voyage. Buffalo Maritime Center, along with dozens of other canal museums, organizations, and related agencies, have researched and shared a more diverse story for the Bicentennial. The Seneca Nation and Buffalo Maritime Center will plant white pines, the tree of peace, along the route. While sharing the full story of the canal doesn’t heal all wounds, it is a more complete history that we can relate to.

As we wrap up this bicentennial, with a World Canals Conference in Buffalo at the end of September that brought over 450 people from ten countries and more than twenty states, with the launching of the replica Seneca Chief, and with a renewed interest in the canal, let us look back and then let us look to the future.

Ninety-nine years ago, in October of 1926 when the Centennial of the canal was celebrated, John D. Wells emcee’d the celebrations at the Statler Hotel in Buffalo.

“In this age of stupendous undertakings we find it difficult to get proper perspective – difficult to understand the task of financing, without proportional volume of money: the vision required to properly inspire the people and promote the enterprise in that early day; of creating without a labor market – in short it is impossible for us to realize the obstacles overcome to create this great public utility which has meant so much to the State of New York and the settlement of her sister States to the westward. We fail because American has progressed so rapidly as to obliterate all standards by which we might make comparison.”

Perhaps, in 2025, we may fall victim again to that lack of “proper prospective.” But perhaps not. We have the benefit of new inspiration, new progress, new research into marginalized people, into the economics, and the vantage of another century. Maybe, as America has grown from those toddler and adolescent years as a nation, New York’s maturity in finding a way into the future to share, preserve and inspire through its history can be a beacon of light, like a lantern at the bow of a canal barge.

— Written by David Brooks, Schoharie Crossing Historic Site Historic Site Assistant. Uncredited historic images are from eriecanal.org.