When the weather turns brisk and the leaves have dropped, tree identification can feel like a puzzle with missing pieces. But winter reveals its own set of clues — bark, buds, branch patterns, fruit and leaf scars. By learning to read these signs, you’ll see your winter woods in a new light.

Bark: The Tree’s First Impression

Bark is often the first clue you’ll notice. Some trees have such distinctive bark that once you have learned to recognize it, you can spot it instantly.

American Beech: Smooth, gray bark, that looks like elephant skin. Even as the tree matures, it holds onto that smooth appearance. Due to widespread Beech Bark Disease, you may see white, woolly spots of the beech scale insect on the bark.

Shagbark Hickory: Long strips curling outward, giving it a shaggy appearance, hence its name. The crevices between the bark and the trunk offer protection and insulation from the harsh weather for overwintering insects, and nooks for food storage for animals active in the winter.

Sycamore: Patchy, mottled pattern of browns, greens, and creams, where the outer bark peels away in irregular shapes to reveal whitish inner bark beneath. Some say it looks like camouflage or a jigsaw puzzle. This process of shedding its bark in pieces is natural and may offer the tree several advantages.

Black Cherry: Dark, rough bark with a scaly texture. The scales are thick and irregular, with faint horizontal lines (lenticels) and slightly upturned edges, giving them the look of burnt potato chips.

Yellow Birch: Golden-brown bark peeling in thin horizontal strips. The shredded, curling bark contains flammable oils, making it a good fire starter (though not as good as its close relative, the paper birch.) However, only harvest bark from dead tree, never a living tree, as this can harm it.

Branch Patterns: Opposite vs. Alternate

If bark doesn’t solve the mystery, look up. Branch arrangement is a fast shortcut to narrow down possibilities. Branch arrangement can be either opposite or alternate. If it is opposite, twigs and buds will develop directly across from each other on the stem. Remember, damage happens, and sometimes branches can fall off. So, don’t just look at two branches, but look at several. If it is alternate, each twig or bud will be staggered along the stem.

Now that you know what the branching pattern is, what do you do with that information? Opposite branching is relatively rare among trees. Use the acronym MADCapHorse to remember those that have opposite arrangement: Maples, Ashes, Dogwoods, CAPrifoliaceae (the honeysuckle family), and Horse chestnuts. All the rest of the deciduous trees have alternate branching— oaks, birches, elms, hickories, etc.

The only exception to this is the Tamarack (aka American Larch), which is a deciduous conifer. Like all conifers, it has a whorled branching pattern, meaning that multiple branches emerge from the same area on the trunk.

Buds: Tiny Winter Time Capsules

Once you’ve narrowed it down based on the arrangement of branches and buds, look closer. Next spring’s leaves and flowers are already packed away into winter buds, ready to spring forth when the season turns. Each tree species’ bud has its own unique appearance.

Sugar Maple: Opposite, sharp, brown buds.

Red Oak: Clustered, pointed buds at twig tips.

Ginko: Small reddish-brown dome-shaped buds grow directly on the remains of last year’s leaf buds, slowly growing stubby peg-like branches called spur shoots.

Horse chestnut: Big, sticky buds that shine in sunlight.

Persistent Fruit and Seeds: Winter Wildlife Resources

Many species hold onto last year’s fruit, nuts, or seed pods through the cold months. They can be spotted in the branches or scattered on the ground beneath the tree, but remember, these are often critical to the survival of wildlife through the winter! The presence of fruit can help you identify or confirm your identification, but the absence does not disprove it.

Red Maple: Papery samaras (“helicopter” seeds) may linger. These winged seeds are particularly beneficial for small mammals and birds who rely on them to build fat reserves and survive the cold.

American Beech: Spiky husks and triangular nuts scattered underfoot. Beech tree nuts are a vital, nutrient-dense food source for many, including black bears, deer, squirrels, chipmunks, and bird species like wild turkeys and ruffed grouse. Beech nuts contain significantly more protein, fat, and calories than acorns, providing a concentrated food source for animals preparing for or enduring winter.

Honey Locust: Long, curling seed pods hanging like ornaments. Honey locust seed pods offer a valuable, high-energy, high-protein food source for wildlife during the late fall and winter. White-tailed deer, squirrels, rabbits, opossums, crows, and other animals consume the nutritious pods which contain a sweet, sugary pulp, rich in sugars that provides a significant calorie boost for animals. The seeds within the pods offer a good source of protein. The combination of sugars and protein makes them valuable and nutritionally balanced.

Black Walnut: Large husks on the ground near the trunk. Despite that pulpy covering and the hard shell around the nut kernels, they are a useful food for squirrels as well as raccoons, turkeys and bears. Like many nuts, the walnut provides protein, carbohydrates and fat, necessary for storing energy for those that hibernate. They are also particularly good for animals that cache the nuts for later. The hard shell protects the nutritious kernel inside, providing a high-protein, high-fat, high-calorie food supply during the lean winter months.

Staghorn Sumac: Bright red fuzzy fruit clusters (drupes) standing upright from the ends of branches. Staghorn sumac provides essential nutrients for more than 300 species of birds, who rely on the persistent fruit clusters when snow and ice cover other sources of food. The berries provide a nutritious, high-fat food source. The fuzzy clusters can also hide insects who provide a crucial protein source even late into the winter.

Leaf Scars: Ghosts of Last Season’s Leaves

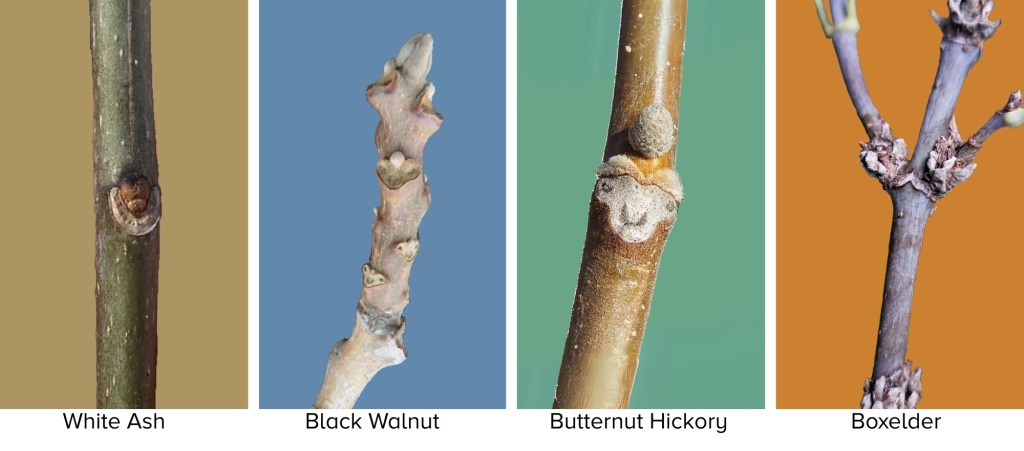

When the leaves drop from a tree leaf scars are left behind and within the leaf scar are vascular bundle scars. Bundle scars are where the “veins” of the leaf connected to the twig. The details of these scars – size, number, position in relation to the bud, color, and shape – can be used as clues.

Ash: Large, horseshoe-shaped scars cupping the bud, typically with clear vein bundle marks.

Walnut and Butternut: Leaf scars shaped like a monkey face — complete with eyes and a mouth formed by the bundle scars. To tell them apart, the butternut appears to have bushy eyebrows.

Boxelder: Narrow, V-shaped scars in opposite pairs that meet at a point.

Case Closed: Nature’s Clues and Nature’s Calm

Winter tree identification is like solving a mystery—each bark texture, bud shape, and lingering seed is a clue waiting to be uncovered. As you slow down to notice these details, you’re not only sharpening your naturalist’s eye, but also giving yourself a chance to step out of the rush of daily life. Taking time outdoors in the quiet of winter can calm the mind, lift your mood, and remind you of the rhythms that carry life through the seasons.

Bring a pocket guide for identifying winter trees with you until you become more familiar, or journal and/or photograph these key characteristics while out enjoying a winter stroll and catch up on the identification when you are back home and warm.

So, the next time you’re out on a chilly walk, let curiosity guide you. Look closely, ask questions, and enjoy the peace that comes from being present in the woods. Uncover the clues, embrace the quiet, and find your own winter wellness.

—Written by Angelina Weibel, Niagara Region Environmental Educator

This was a very understandable article for someone like me who hasn’t done tree identification using a tree key book in 50 years! Well done, Angelina – I am inspired to take a closer look around me next time I walk past a tree this winter.

All the best –

Karen Russell

Great! Is there a “print friendly” version?

We don’t have a print-friendly version, sorry!