How do you clean an egg more than a century old? Very, very carefully…

That was the challenge facing conservator Heidi Miksch at the State Park’s Historic Preservation Division at Peebles Island State Park. She had just gotten a case of bird eggs that had been collected in the late 19th century by the children of famous Hudson River School landscape painter Frederic Church.

While growing up in the family home at Olana in Columbia County, Church’s four children were part of the then-popular hobby of bird egg collecting, also known as oology or “birdnesting.” The children managed to collect and fill a large case with hundreds of specimens in wooden trays, each in a small labeled box lined with cotton.

The case had been stored ever since at what is now the Olana State Historic Site, where staffers intend to display part of the collection for the first time ever this spring in an exhibit on connections between art and the environment.

*** UPDATE***

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this display was cancelled last year. It is now scheduled for June 12, 2021 through October 31, 2021.

But many of the eggs were blackened with decades of dust and grime, and had to be cleaned before being displayed. So Miksch, who has conserved objects from a stuffed black bear to a piece of the Parthenon, researched a bit, and came up with her technique _ using conservation-grade cotton swabs, a dab of water, and gently rubbing. An average-sized egg takes about 20 minutes to clean, and the case contains eight trays, each with 36 boxes with most boxes containing one or more eggs. Miksch uses water, and not a cleaning solution, for fear of degrading the delicate eggshells.

Click through the slideshow as conservator Heidi Miksch (wearing the blue sweater) shows the Church childrens’ egg collection.

“The Church children collected many different kinds of eggs,” said Miksch. “I have even found a flamingo egg in there.” (For the record, a flamingo egg is white and oval in shape, appearing much like an oversized chicken egg.)

In the early 20th century, conservation concerns over the impact of bird egg collecting began to mount, and the practice later was limited in the U.S. under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

But when Church’s children – Frederic, Theodore, Louis, and Isabel – were growing up in the Hudson Valley during the 1870s and 1880s, egg collecting was seen as a good way for children to learn about nature while also engaging in healthy outdoor exercise.

To preserve a collected egg, a tiny hole would be drilled into it, and the contents would be aspirated out of the hole, and then the egg would be rinsed out to prevent rot and decay. Or two holes could be drilled and then the contents would be blown out. The empty egg was then carefully stored.

Egg collecting was not just a hobby for children. Cultured gentlemen of the era, particularly in England, amassed large collections and ranged over many nations in pursuit of rare or unusual eggs. One of the world’s richest men at the time, English financier Baron Rothschild, had a collection of nearly 12,000 bird eggs, which now resides in the British Museum of Natural History.

Egg collecting was at its zenith from about 1885 through the 1920s, with children being the vast majority of collectors, according to a 2005 research paper by Lloyd Kiff, past director and curator with the California-based Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

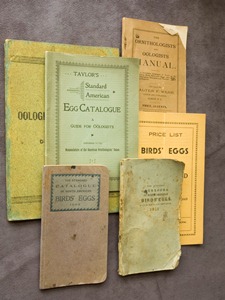

Collectors of the day would trade eggs among themselves. There also were commercial egg sellers, who would offer eggs for sale in catalogs, just like dealers in stamps or coins.

An American collector, William Brewster, who in the 1880s was the chair of the American Ornithologists’ Union Committee on Bird Protection, collected thousands of eggs that are now held in the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University in Massachusetts.

But the hobby began dying out as conservation principles and legal restrictions took hold, and by the 1940s the practice was all but gone. Today, it is illegal to collect bird eggs in the U.S. without a permit issued for research purposes.

The practice is also outlawed in England, although a few fanatical collectors persist despite legal sanctions.

Kiff’s study estimates that there about 80 major egg collections in the U.S., composed of about a half million egg sets, representing some two million individual eggs. These collections have demonstrated significant scientific value in subsequent years, supporting the discovery that exposure to the pesticide DDT was causing eggshell thinning in birds like bald eagles, Peregrine falcons, and pelicans.

This evidence formed the basis of a $140 million federal government settlement with DDT manufacturers in 2001, which Kiff described as the most important ecological use of any bird-related specimens.

“By now, hundreds of eggshell-based studies of (DDT) have appeared in all major regions of the world, and the present ban on DDT use in all but a handful of countries is a direct result of this research.” – Lloyd Kiff

History, Present Status, and Future Prospects of Avian Eggshell Collections in North America, The American Ornithologists’ Union (2005)

He suggests that eggshell collections may also be useful in the future for the study of ongoing climate change and its impacts on birds.

This comes as expertise in this field is fading away, Kiff wrote, adding “The body of traditional oological knowledge may vanish, except on the browned pages of extinct journals, and existing egg collections may gradually become objects of greater interests to historians than to biologists.”

If you would like to see the eggs collected by the Church children displayed in the home where they grew up, visit Olana between May 9 and Nov. 1 for the exhibition entitled “Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church, and Our Contemporary Moment.”

This exhibition features Martin Johnson Heade’s 19th-century series of hummingbird and habitat paintings – The Gems of Brazil – and their relationship to Hudson River School landscape painters Thomas Cole and Frederic Church.

Co-organized by the Olana State Historic Site, The Olana Partnership, and the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, as well as the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas, this exhibition will also feature work by contemporary artists including Nick Cave, Mark Dion, Jeffrey Gibson, Paula Hayes, Patrick Jacobs, Maya Lin, Dana Sherwood, Rachel Sussman, and Vik Muniz.

Cover Shot- Close-up of part of the Church children’s egg collection. (All photos and videos by NYS Parks unless otherwise noted)

Brian Nearing, Deputy Public Information Officer, NYS Parks

Resources

History, Present Status, and Future Prospects of Avian Eggshell Collections in North America, 2005, Kiff, Lloyd L., American Ornithological Society.

The Code of Nomenclature and Check-list of North American Birds

Ornithologists and Oologist, Semiannual, January 1889 – Victorian-era instructions on collecting and preserving. Explains collector practices of the time period.

Fragile Beginnings: Bird Egg Collection – Blog post on collection decisions made at Wesleyan University

University of Wisconsin – Searchable online database for egg identification