Environmental conservation was a driving force in creating New York’s state parks system that you know and love today. From protecting Niagara Falls from industrial development to preserving the views outside of Albany at Thacher State Park, our agency has been working to preserve our lands and make them available for public enjoyment since its founding. This simple mission has taken on a different meaning in the face of climate change and the shift to clean energy. Here are some ways we’re meeting the challenges of environmental conservation in the 21st century.

Shifting to Renewable Energy

New York State Parks is charged with shifting all operations to renewable energy by 2030, either through the purchase of renewable energy or through generating our own.

Statewide, Parks operations consume around 45 million kilowatt hours of electricity (the same annual usage as about 4,000 homes). The agency currently has 50 solar arrays around the state generating more than 6MW, which help reduce carbon emissions and save money. This includes everything from roof-mount arrays to large ground-mounts built in pre-disturbed areas like the back of parking lots.

Complementing these installations is our shift away from gasoline-powered equipment towards electric. Electric landscaping equipment has the side benefit of reducing noise, benefitting both patrons and employees. The agency aims for all purchases of new hand-held landscaping equipment to be electric by 2025. Parks is also electrifying our vehicle fleet, replacing light-duty vehicles with electric. This year, the agency purchased its first electric truck, for Robert Treman State Park.

Land Stewardship and Habitat Restoration

Quality stewardship of our lands is a core component of our mission. Sometimes, that means significant restoration work. Other times, that means considering the earth in projects benefitting visitors. Some recent major stewardship projects include:

Restoring historic estuary habitats at Schodack Island State Park. A century ago, five islands in the Hudson River south of Albany were joined and connected to the eastern shore to create a shipping channel from New York City to Albany, eliminating critical habitat. This new peninsula is now known as Schodack Island State Park. State Parks is working with NYSDEC and the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve to restore these historic habitats. By restoring this historic connection between the Hudson River and the backside of the peninsula, we will essentially “re-island” the park. The connection will recreate six acres of channel and tidal wetlands and enhance habitat for aquatic life up and down the estuary.

Niagara River habitat restoration. Historically, the upper Niagara River supported extensive coastal wetlands and diverse aquatic habitats. Development and industry in the past have severely modified habitat and water quality in the Niagara River system. To help restore the river system, five wetland and shoreline restoration projects have been completed by OPRHP staff since 2019—all funded through the EPA Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Additionally, a wetland creation project is in construction at Beaver Island State Park near Buffalo with more projects planned. These projects are contributing to a healthier Niagara River and Great Lakes Basin for all.

Big Bend Preserve opening soon. Through a partnership with the Open Space Institute, State Parks added 870+ acres to Moreau Lake State Park in 2021. This land, appropriately named Big Bend Preserve, sits in a large bend of the Hudson River near Glens Falls. Our Stewardship staff saw the restoration potential of this formerly logged land, and worked with Albany Pine Bush Preserve Commission, NYSDEC, and US Fish and Wildlife Service to develop an Ecological Management Plan. This plan will restore and protect Big Bend’s diverse habitats with a focus on enhancing 450 acres of sand barrens habitats for the federally endangered Karner blue butterfly.

Green parking at Mills Norrie. Sometimes a parking lot is more than just a parking lot. At Mills Norrie State Park in Staatsburg along the Hudson River, the Norrie Point parking lot has received a massive green infrastructure upgrade. The lot serves the Norrie Point Environmental Center, run by the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve (NYSDEC, NOAA), and marina. Updates include permeable pavements alongside pocket wetlands to improve stormwater treatment, EV charging stations, bike racks, easier access to a restored Hudson River shoreline, native plantings, interpretive signs, marsh migration space, seawall rehabilitation, and dark sky lighting.

Reducing, Reusing, Recycling

Parks has a longstanding commitment to waste reduction and landfill diversion. Each year, our parks compost thousands of tons of yard waste and recycle a wide variety of materials, from plastic bottles to asphalt. As part of a five-year plan to reduce landfill waste by 10 percent, Parks is conducting waste audits; implementing actions to reduce, reuse, and recycle specialty waste; expanding its existing recycling and composting programs; and increasing its outreach and education efforts for patrons.

Supporting Natives, Stopping Invasives

The fight against invasive species never ends. It requires consistent effort when it comes to mitigation, but it’s a battle worth waging. Recently, we’ve successfully removed invasive water chestnut from Sterling Pond at Fair Haven Beach State Park and replaced invasive Japanese Barberry with native plants at Clarence Fahnestock State Park. We’re in the midst of a two-year project to remove invasive trees along 6.5 miles of the West River Shoreline Trail, located along the Niagara River between Buckhorn Island and Beaver Island State Parks. These projects support native species of all kinds, improve views, and make for a better habitat.

Educating the Public

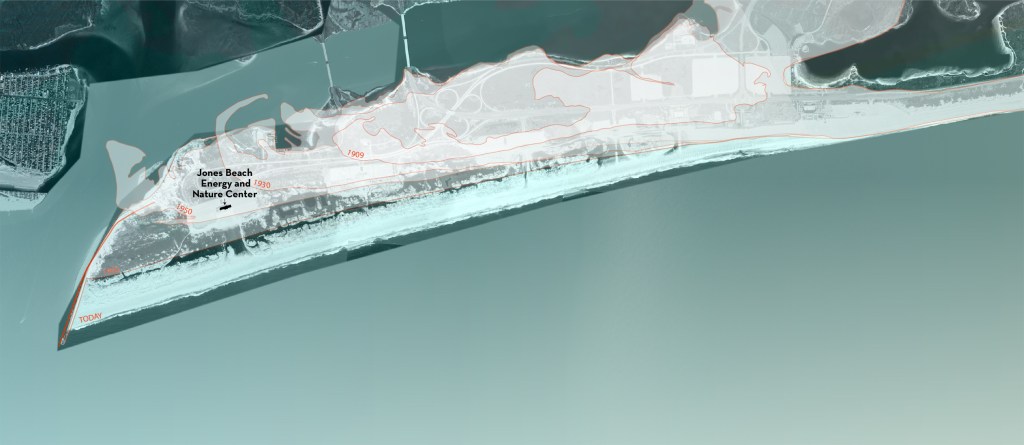

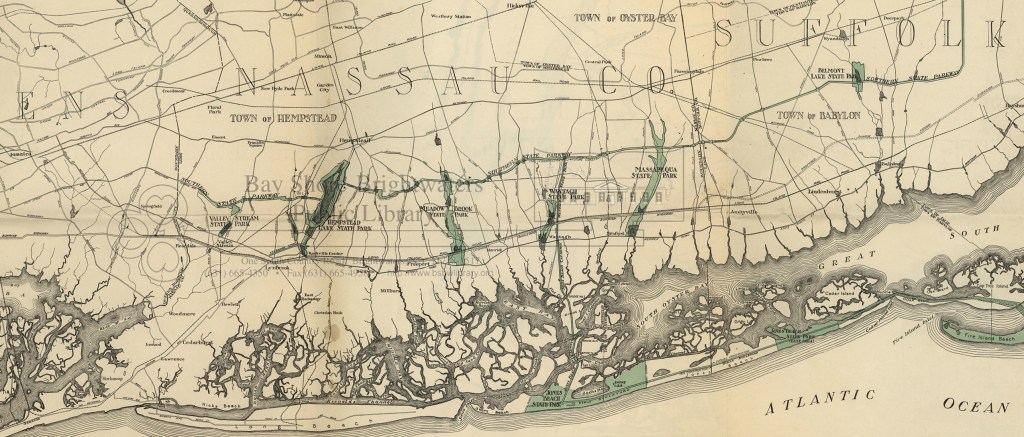

Environmental educators love to share their knowledge of our natural world with people of all ages. Most of our 250 parks and sites include an environmental education component, whether it’s interpretive signs, visitor center exhibits, or guided hikes and other programs. The Jones Beach Energy and Nature Center is dedicated to exploring the many connections between ecosystems and energy systems, such as how energy cycles in natural systems, as evidenced in the cycles of plants and animals along Jones Beach; how built energy systems such as cities, suburbs, and transit networks shaped the environment; and how energy consumption affects global climate change, the impacts this has on ecosystems, and how this interplay may shape New York in the future. The net-zero building design is a model of modern clean energy technology, including a geothermal HVAC system as well as solar panels and battery backup for power.

-Written by Daniel Fleischman and Chloe Hanna (Division for Environmental Stewardship and Planning), Caitlin Tremblay (Energy Bureau), and Kate Jenkins (Public Affairs Bureau)