There is a rich heritage of New York history all around us to explore during Black History Month this February.

While the stories of civil rights icon Martin Luther King, Jr., his march at Selma, Alabama, and 19th century abolitionist Fredrick Douglass are well known, these people and places represent only a small part of our common cultural landscape.

Some of this fascinating African American history is closer to home, right here in New York State. This year, how about delving into New York’s own aspects of Black history by learning more about our own unique people and places?

Using the state’s parks, historic sites, the historic preservation agency, and I LOVE NY’s Path Through History and blog, you can find nearly four hundred years of interesting stories effortlessly, on such topics as the our state’s role in the the Civil Rights movement and the Underground Railroad, a network a network of secret routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early to mid-19th century, and used by enslaved African-Americans to escape into free states and Canada.

In the U.S., Black History Month traces its origins to 1915 and the national 50th anniversary emancipation celebration in Chicago, where African American historian, author and journalist Carter G. Woodson staged a history exhibit. In1926, Woodson selected the second week in February for Negro History Week as a nationwide event. It grew into a month-long celebration and was federally recognized by President Gerald Ford in 1976 during the U.S. Bicentennial.

To learn more about Dr. Woodson’s life and work, and his founding of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), visit https://asalh.org.

Figuring out where to begin on such a historical journey in New York may seem challenging, but here are some ideas to get you started. We hope you enjoy your step into the extraordinary history of Africans and their descendants.

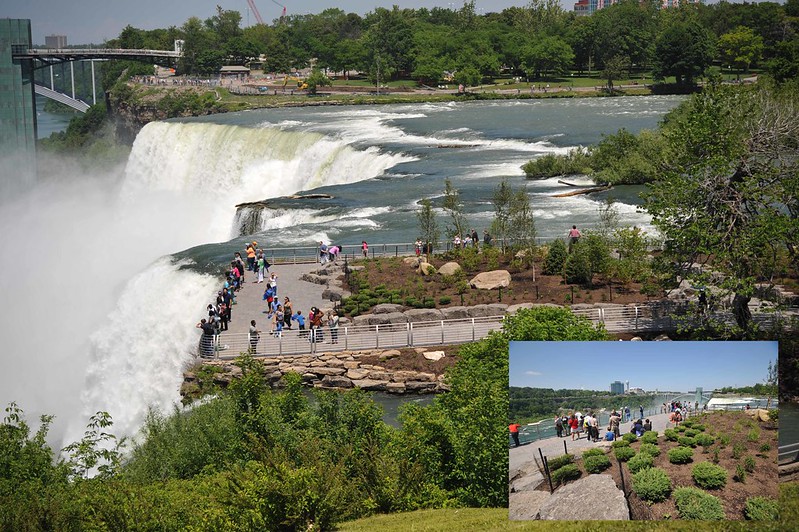

Niagara Falls State Park, 332 Prospect St., Niagara Falls, USA: On Feb. 13, the falls will be illuminated in red, black and green (colors of the Pan-African flag) starting at 6 p.m., for a 15-minute period at the top of the hour continuing through 11 p.m.

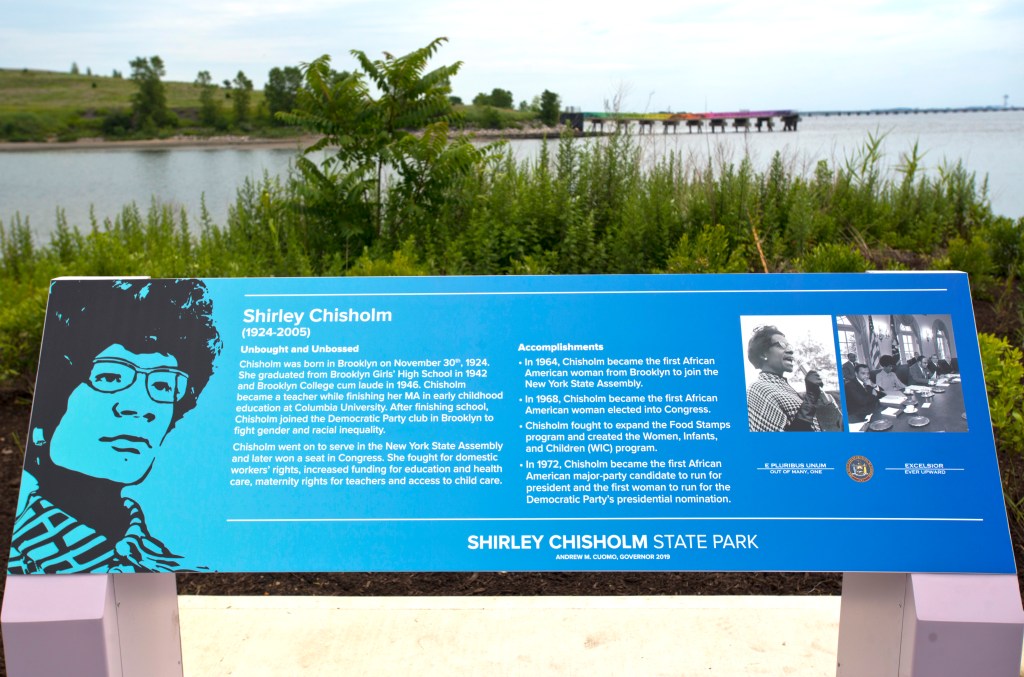

Shirley Chisholm State Park, 950 Fountain Ave., or 1750 Pennsylvania Ave., Brooklyn: Named in honor of Shirley Chisholm, a Brooklyn-born trailblazer who was the first African American Congresswoman, as well as the first woman and African American to run for President. As 507 acres, this amazing park leads you into the life of Ms. Chisholm, and also into the wonderful world of environmental justice. Sitting on a reclaimed landfilled, the paths and views of Jamaica Bay can refresh your spirit while introducing you to one of New York’s most noted Black politicians.

Walkway Over the Hudson State Historic Park, 87 Haviland Road, Highland: Although many people think Sojourner Truth was from the South, this former enslaved woman, abolitionist and suffragette was actually born and raised in Ulster County and grew up speaking Dutch. In August of 2020, a bronze statue of her was unveiled at the main entrance of Walkway Over the Hudson State Park in Highland. Learn more about her life, and about Vinnie Bagwell, the African American sculptor who made the statue, here.

Jones Beach Energy & Nature Center, 2400 Ocean Parkway, Wantagh: The newly opened Center will be offering several programs during the month of February, including an exhibit of Black History related posters, including Heroes of the Great Outdoors shown below. The center is also hosting socially-distanced showings of No Time To Waste: The Urgent Mission of Betty Reid Soskin. The film shares the story of an amazing 99-year old National Parks Ranger’s inspiring life, work, and urgent mission to restore critical missing African American chapters of America’s story. The center is also hosting free online screenings of this film from Feb. 11 to 15. Registration is available here.

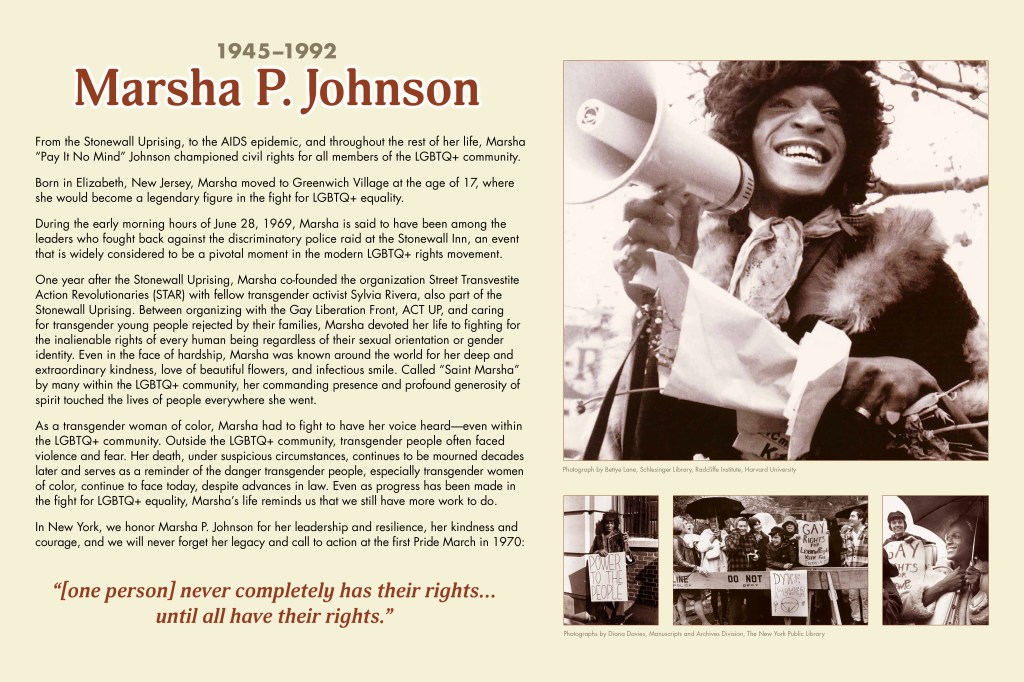

Marsha P. Johnson State Park, 90 Kent Ave., Brooklyn: Renamed for a transgender African American woman and dynamic pioneer who advocated for the LGBTQ+ and HIV/AIDS communities, this seven-acre park in Brooklyn offers a river front view of Manhattan and an opportunity to relax in a place where everyone is welcome.

Note: the park is undergoing extensive renovations including the installation of public art honoring Marsha P. Johnson and the LGBTQ+ community. Some areas of the park will be temporarily limited during construction to be completed June 2021. The north section of the park will remain accessible through neighboring Bushwick Inlet Park.

Old Fort Niagara State Historic Site, Youngstown: A Feb. 6 tour highlighting African American military service at post from the 18th through the 20th centuries, including the story of formerly enslaved Richard Pierpoint, who served during the American Revolution. The tour will also address the history of the 24th Infantry Regiment, a unit of African American “Buffalo Soldiers” raised after the Civil War. Tour size is limited to 20 persons, and preregistration is required by contacting Erika Schrader at 716-745-7611, ext. 221, or eschrader@oldfortniagara.org.

Clermont State Historic Site, 1 Clermont Ave., Germantown: A free walking tour at 2 p.m. Feb. 21 on the role of the Livingston family, as well as their enslaved people and tenants on their estate, during the Revolutionary War.

National Purple Heart Hall of Honor, 374 Temple Hill Road, Route 300, New Windsor: The mission of the newly reopened National Purple Heart Hall of Honor is to collect, preserve, and share the stories of all Purple Heart recipients. There and online you can learn about our brave service men and service women including men like Ensign Jesse L. Brown, the first African American naval aviator during the Korean War. You can also learn about registering a Purple Heart recipient for the Roll of Honor.

New York also has many sites of African American history on the State and National Register of Historic Places, including:

Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest & Ninevah Subdivisions (SANS), Sag Harbor, Suffolk County: The Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest, and Ninevah Subdivisions (SANS) Historic District, is a mid-twentieth century African American beach community on Long Island that has and continues to serve as a retreat created by and for families of color. Famous individuals who summered at SANS included Langston Hughes and Lena Horne. The district’s stewards are the recipients of a 2019 NYS Historic Preservation Award.

Stephen & Harriet Myers Residence, Albany, Albany County: The Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence was a headquarters for Underground Railroad activity in the Capital Region in the mid-1850s, as documented by a Vigilance Committee flier that has survived from that period with additional historic records. Today the site is operated by the Underground Railroad History Project of the Capital Region as a historic site where the community can learn about the Underground Railroad, the first integrated Civil Rights movement in the United States, and its relevance to today. This site is the recipient of a 2015 NYS Historic Preservation Award and was also featured in the “We Are NY” series. and the Underground Railroad Education Center

James Baldwin Residence, Manhattan (Harlem), New York County: Prominent author and activist James Baldwin (1924-1987) lived in this building during his last decades, 1965-1987. Baldwin made profound and enduring contributions to American literature and social history, addressing the major questions America faced in those decades. Recently, portions of Manhattan park were renamed after James Baldwin to further honor his legacy. His former home is featured in the New York City LGBT sites project.

John W. Jones Museum, Elmira, Chemung County: The John W. Jones House in Elmira is listed in the State and National Registers of Historic Places and is now a museum open to the public. John W. Jones became an active agent in the Underground Railroad in 1851 and continued to help enslaved individuals escape to freedom for many years. The museum explores Mr. Jones’ community involvement and his relationship with his contemporaries, as well as the location’s function as the only Underground Railroad station between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and St. Catharines, Ontario Canada.

Colored Musicians Club, 145 Broadway, Buffalo: Formed in 1917, the Colored Musicians Club was one of the oldest continually operating African-American musicians’ clubs in the country as well an office for Buffalo Local 533, an early African-American union of musicians. These organizations were part of the response to racism and segregation in Buffalo’s musical community. The Colored Musicians Club was home to performances by such notable artists as Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Nat “King” Cole, Miles Davis and Cab Calloway.

Given the need for social distancing amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, NYS Parks also has an array of virtual and online events and information. Here are a few examples:

John Jay Homestead State Historic Site, Katonah: A Zoom lecture on the history of enslavement in this prominent Colonial-era family starts 7 p.m. Feb. 24. Registration available at www.johnjayhomestead.org The website also includes virtual exhibits, school programs and tours to explore the Jay family’s history as enslavers, and the dedication of later generations of Jays to the abolitionist cause.

Olana State Historic Site, Hudson: A webinar on the life of 19th century African American and Ojibwe sculptor Mary Edmonia Lewis, presented by University of New Mexico professor Kirsten Buick. Starting 6 p.m. Feb. 24, access to this event requires paid membership in The Olana Partnership available at www.olana.org/membership.

Jay Heritage Center, Rye: A Zoom lecture by Dr. Gretchen Sorin, director of Cooperstown Graduate Program in Museum Studies, on her new book, “Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights” will be held 7 p.m. Feb. 11. Registration is available here.

Clermont State Historic Site, Germantown: A Facebook Live event starts 2 p.m. Feb. 20 hosted by comic artist Emily Ree on how the Red Scare of the 1950s led to blacklisting in the comic book industry, which at the time supported a diverse workforce of people of color and women.

Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site, Albany: In 1793 a good portion of the City of Albany burned down. Three enslaved Africans were accused of setting the blaze. In this fictionized drama based on historic evidence, see how the community of enslaved and free, Africans and Europeans interacted during this tense time in a legal system where the enslaved had little voice. Here is a guide to The Accused: Slavery and the Albany Fire of 1793.

Facebook posts on African American related items from Parks’ historic sites are also available, including:

Fort Montgomery State Historic Site, Fort Montgomery: This post offers a glimpse into the life of Benjamin Lattimore, one of the few known African American soldiers to fight in this 1777 Revolutionary War battle in the Mohawk Valley.

Fort Ontario State Historic Site, Oswego: This post describes the World War II training of Harlem Hellfighters, the segregated African American 15th New York National Guard Regiment who were stationed at the fort.

Formerly the 15th NYNG Infantry Regiment, the unit was activated into federal service and began training as the 369th Coast Anti-Aircraft Artillery Regiment at Fort Ontario in January 1941. This occurred after FDR federalized the National Guard in preparation for WWII. It was the first opportunity for blacks to serve in a technical role in the U.S. Armed Forces, a milestone in the Civil Rights movement. The regiment is now the 369th Sustainment Brigade with an armory on 5th Avenue in New York City.

Shown below is the 369th depicted in a promotion for the Netherland Dairy of Oswego which supplied the 2,000-man garrison with milk. It appeared in the May 28, 1941 issue of the Post Script, the regiment’s newspaper while stationed at Fort Ontario until September 1941.

And finally, the New York State Parks Blog also has recent posts on African American historical items, including the Dutch colonial-era African American holiday of Pinkster, 19th century abolitionist Sojourner Truth and her life in the Hudson Valley, the 19th century emancipation holiday of Juneteenth which last year became an official state holiday, and the role of African American leadership in the Civilian Conservation Corps in New York State during the Great Depression.

So, take advantage of these many opportunities to learn about the history of people and places that form a more complete story of New York State.

Cover Shot: African American Cemetery in Montgomery, Orange County, believed to hold graves of about 100 people, mainly slaves brought to the region in the mid-18th cemetery. (Photo Credit – Lavada Nahon) All other photos from NYS Parks unless otherwise noted.

Post by Lavada Nahon, Interpreter of African American History, Bureau of Historic Sites, NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation