Native plant gardening is one of the most important ways to take sustainable action, creating habitat for indigenous wildlife while preventing the spread of invasive species. Growing plants from seed has the benefit of higher genetic diversity than planting nursery stock, which is often cloned.

Better yet, locally sourced seeds are part of the local ecotype, or the genetic variety adapted to your area. The more locally your seed was harvested, the better your garden will help preserve your ecosystem in the face of climate change, invasive species, and other threats to our landscape.

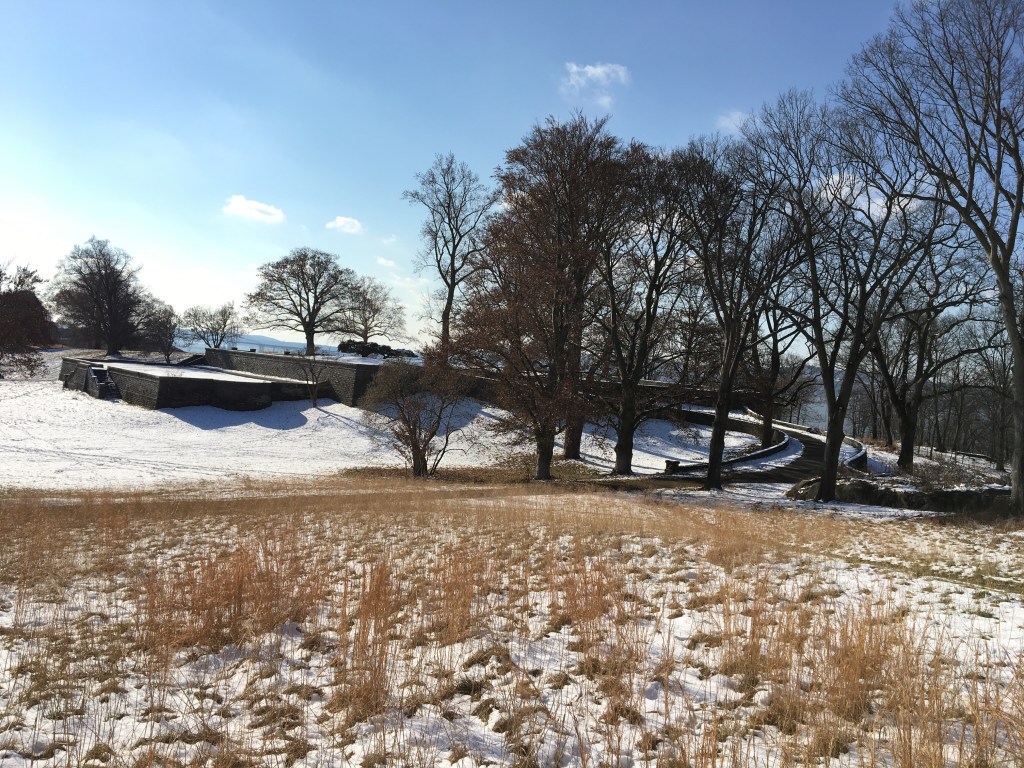

That’s why Rockefeller State Park Preserve held a series of gardening workshops this winter. Yes, you read that right—the gardening season starts in winter! Native wildflowers are adapted to the climate of this region, so they’ve evolved to need the cold of winter to break through the outer coating of their seeds. This is called cold stratification. Sowing by mid-February ensures that your seeds have enough time in the cold to germinate by mid-April when the weather warms up.

While the preserve’s Native Wildflower Seed Sowing Workshops are over, here’s a handy guide to follow along at home.

Sourcing native seeds

The best way to get seeds of your local ecotype is through a local seed collecting organization that already has the licenses and permissions to legally and ethically source seed. It’s important not to attempt harvesting seeds yourself without appropriate licensing and training, as this can threaten the natural population of the plant. Healthy Yards is a coalition of public and private landowners in Westchester County working together to provide locally-sourced seed to home gardeners. If you don’t know of such an organization near you, I’ve added some resources at the bottom of this article. Planting the seeds of a New York native plant is better than planting nonnative nursery stock, even if it’s from a different ecotype.

Preparing your materials

You will need a container and soil. Reuse a plastic salad container or milk jug with a lid to maintain humidity, and punch drain holes in the bottom. Label it with the name of the plant, the date sown, and the expected germination date. For soil, sterile seed starting mix can be bought from nurseries and gardening stores. In a shallow plastic container, moisten the soil by mixing it with hot water with your hands. Hot water and steam will penetrate the soil more quickly than cold water, so you won’t need as much to get your soil just slightly moist. Too much water could lead to seed rot.

Scoop the soil into the container until it’s two-thirds full and gently smooth the surface, without compressing it.

Sow the seeds

Sow seeds at a depth equal to the size of the seed itself. A larger seed should go in a depression in the soil with a light layer of soil on top, while tiny seeds may be sprinkled on the surface. An easy way to surface sow tiny seeds is to mix them with sand in a salt or spice shaker. The sand will show you how much you’ve sown, and is easier for light to penetrate than soil, sometimes a requirement for native seeds.

Wait

Seal the container and place it outdoors or in an unheated room. Mark your calendar for the expected germination date. Check the moisture level periodically, giving a spritz of water if they’re drying out.

Germination and Beyond

When the weather starts warming and your germination date approaches, check on your seeds every day to see if they sprout. When you see cotyledons, or the first leaves, remove the lids and place them in the sun. These leaves were contained in the embryo and will not look like the representative leaves of the plant.

Now that the lid is off, you’ll have to monitor the moisture more often. You can place a tray under the container to hold some water to prevent drying out. Once the first set of true leaves emerge, transplant each seedling into its own pot with potting soil and compost. At this point, care for each plant according to its individual moisture, soil, and light requirements.

When they’re big enough, plant them in your garden by mid-June and water daily until they begin to put on new growth. If they aren’t ready to be planted by June, then keep them in pots until fall as they are less likely to establish in the heat of summer. Continue to water and remove any surrounding weeds or competing plants. Don’t worry if all your seedlings don’t survive or if the plants don’t flower the first year. Some plants take a year or two to get established.

Enjoy watching your seedlings grow to attract bees, beetles, butterflies and other interesting insects. In the winter, leave foliage and seed heads to provide shelter and food for overwintering insects and birds. Your native plant garden will help bridge the gap between nature and your neighborhood.

Cover Shot – Bluets (Houstonia caerulea), a native spring wildflower that can form delicate carpets of pale blue on dry sunny sites. A classic rock garden plant and groundcover. Photo Credit – State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Post by Devyani Mishra, Flora Steward, Rockefeller State Park Preserve

Resources

Bringing Nature Home by Doug Tallamy is a call to action for planting native plants in your garden that describes how your yard can help your ecosystem.

This website from the state Department of Environmental Conservation lists native flowers for gardening and landscaping.

The following websites can help you find plants native to your area:

Native Plant Finder (By Zip Code) , Xerces Society Pollinator Conservation Resource Center, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center New York Special Collection

Here are some responsibly sourced seeds that serve the Northeast and the Great Lakes regions. These sources include plants that aren’t native to New York, so be sure to double check with the New York Flora Atlas that the plant you want is native to your area:

Prairie Moon Nursery, Ernst Conservation Seeds, Eco59, WildSeedProject.net, OPN Seeds, Hudson Valley Seed Company

Here are some native plant societies around New York that may know more about locally sourced seed in your area:

Finger Lakes Native Plant Society, Adirondacks Garden Club, Long Island Native Plants Initiative, Torrey Botanical Society, Niagara Frontier Botanical Society