As the third most common tree in New York, hemlocks fill our forests and are found in many New York State Parks. Located along hiking trails, streams, gorges, campsites, and lake shores, the evergreens can live to be hundreds of years old, providing vital ecosystem services and supporting unique habitats.

In addition to providing homes and food for many forest creatures, hemlocks also keep fresh water resources cool and clean by moderating water temperature and acting as a natural filtration system along streams. Since hemlocks are such a critical component of eastern forests, they are known as a “foundation species.”

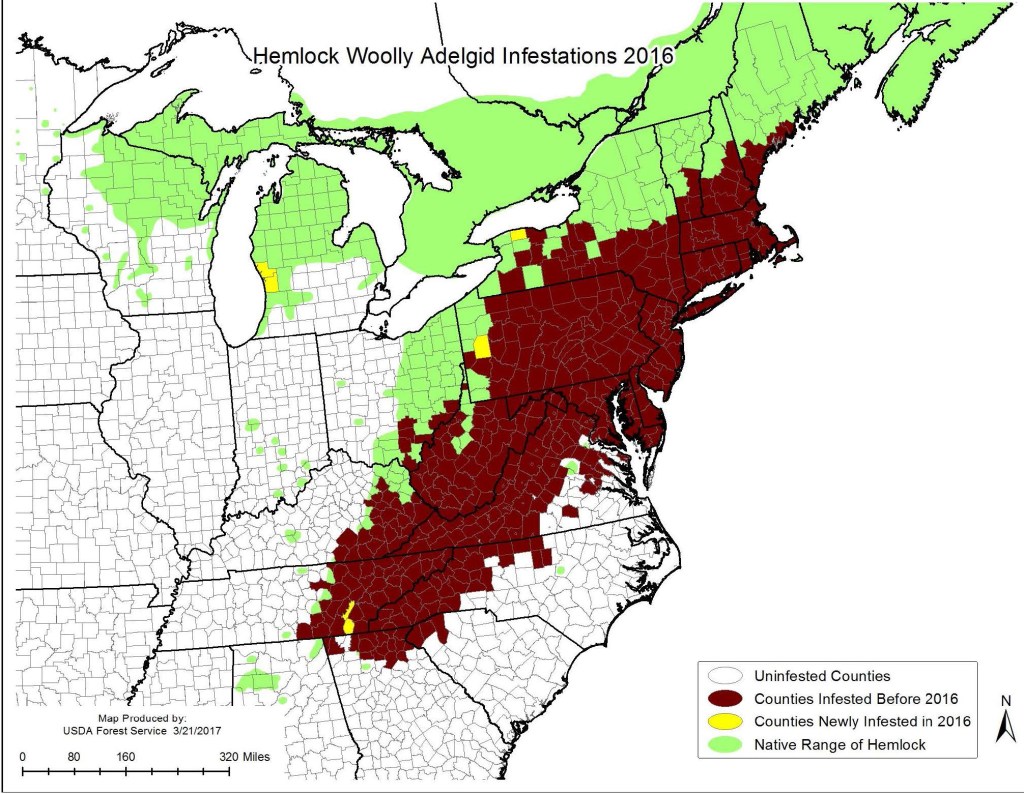

Hemlocks in New York have been under attack by an invasive forest insect pest that originated from southern Japan, the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), which after being found in Virginia in the 1950s has spread to kill untold millions of hemlocks from Georgia to Maine.

Adelgids are tiny insects that insert piercing-sucking mouthparts into hemlock twigs, causing damage to woody tissue that inhibits water and nutrients from reaching emerging hemlock buds. This limits the growth of new twigs and eventually kills the tree.

First detected in New York in the 1980s, the insects have spread through the Hudson Valley, Catskills, Southern Tier and Finger Lakes regions. Infested hemlocks can be found at state parks including Harriman, Minnewaska, Taughannock Falls, Watkins Glen, Letchworth, and Allegany.

At about 6/100ths of an inch long, the flightless adelgids are hard to spot, but in the winter through early summer leave distinctive white “woolly” egg masses on hemlock twigs. In an infestation, developing buds are killed first, then in a few years, the weakened tree loses its needles and dies.

The threat posed by HWA is dire, especially since the state’s ecosystems lack natural controls _ known as biocontrols _ such as predators or tree resistance that could fend off some infestations and avert widespread hemlock destruction.

Currently, insecticide treatments are our only sure option for saving trees, but trees must be treated on an individual basis, so it can be costly or impractical to treat large swaths of hemlocks. In parks with thousands of trees and important or rare ecosystems to protect, biocontrol is the only solution to counter a pest like HWA.

But biocontrol against the invading adelgid may be on the way. It is the form of a small dark beetle and a small silvery fly, nicknamed “Little Lari” (Laricobius nigrinus) and “Little Leuc” (Leucopis spp.), respectively, by researchers at the New York State Hemlock Initiative at Cornell University.

Led by forest entomologist Mark Whitmore, the program operates a biocontrol lab researching the introduction of HWA predators throughout New York, hoping to protect hemlock trees by slowing the spread of adelgids into new areas.

The NYSHI collects these predators in the Pacific Northwest where HWA is native and has many predators controlling population growth so the hemlocks are not damaged. The collected beetles and flies are shipped to the quarantine facility at Cornell to be certain none of the western adelgids are accidentally introduced into New York with the predators.

Knowing where to release these “good bugs” can be a challenge, but we are helped in this by State Parks staff, who provide critical data from ground surveys to find emerging infestations, assess potential biocontrol sites, and monitor for whether the biocontrol insects are thriving and growing in their new homes.

Read this post in the State Parks blog by Abigail Pierson, state Parks Forest Health Specialist, to learn how crews search for and document the presence of HWA.

Since 2009, the Cornell initiative has released more than 4,500 Laricobius beetles in State Parks including Harriman in Rockland County, Letchworth in Wyoming County, Mine Kill in Schoharie County, and Taughannock Falls, Buttermilk Falls, and Robert H. Treman in Tompkins County. Additionally, parks staff at Minnewaska State Park Preserve in Ulster County helped survey for Laricobius beetle establishment, and mapped hemlocks to help identify hemlocks stands and prioritize HWA surveys in the park.

Since 2015, when Leucopis silver fly releases began, researchers have released more than 3,300 flies at several state park sites including Taughannock Falls and Buttermilk Falls state parks in Tompkins County.

While there has been no evidence of the biocontrol bugs suppressing HWA populations on a large scale, it takes time for predator populations to build. There has been recovery of Laricobius beetles at some sites, indicating establishment. By continuing to release more “Little Laris” and “Little Leucs” to bolster those established populations, we will be able to build on that initial success.

The list of parks that have reported HWA infestations is growing, especially in the Capital Region. Thacher State Park in the Capital Region reported adelgid infestations in 2017 and while insecticide treatments reduced the local problem, the insects continue to threaten the Adirondacks, which so far remains uninfested.

In State Parks, preventing dead trees from injuring park visitors or damaging park infrastructure including campsites and trails is crucial. Additionally, preventing the loss of a critical foundation tree species in forest habitats is another major priority.

Park visitors can play an active role in slowing the spread of the adelgid in New York by keeping an eye on hemlocks. Reporting any infestations that you find provides researchers and land managers with invaluable data for improving our management efforts.

How You Can Help

If you believe you have found HWA:

- Take pictures of the infestation signs (include something for scale such as a coin or ruler).

- Note the location (intersecting roads, landmarks or GPS coordinates).

- Fill out the hemlock woolly adelgid survey form.

- Email report and photos to Department of Environmental Conservation Forest Health foresthealth@dec.ny.gov or call the Forest Health Information Line at 1-866-640-0652.

- Contact your local Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management (PRISM) by visiting http://www.nyis.info/.

- Report the infestation at iMapInvasives.

- Slow the spread of HWA in our forests by cleaning equipment or gear after it has been near an infestation, and by leaving infested material where it was found.

The New York State Hemlock Initiative has produced a variety of educational videos on the threat posed to hemlocks by the HWA.

Cover Photo: A hemlock branch showing the woolly white egg masses of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. (New York State Department of Environmental Conservation)

Post by Charlotte Malmborg, Education and Outreach Technician, New York State Hemlock Initiative, Cornell University Dept. of Natural Resources