Across New York, outdated infrastructure is getting a second chance to serve communities. Former factories, railroads, and hospitals are now spaces for New Yorkers to get outside, get some exercise, and disconnect from their electronic devices. In this new series, we explore how your favorite state parks once served a very different but equally important purpose to our state.

In this first installment of Infrastructure’s Second Act, fasten your seatbelts and learn about the state parks built from former transportation infrastructure, including railroads and canals. These sites served as critical community connectors in the past, and now connect communities in a much different way: as places to recreate, relax, and enjoy the natural world.

Walkway Over the Hudson State Historic Park

The world’s longest elevated pedestrian bridge, the Walkway Over the Hudson is a Hudson Valley icon. Whether you’re going up, down, or across the Hudson River, the Walkway demands your attention as it glistens in the sunlight. But before it was a recreation destination, the 1.28-mile steel cantilever bridge served as a vital piece of New York’s rail network during the 19th and early 20th century.

The Walkway Over the Hudson was constructed in 1889 and was known as the Poughkeepsie Bridge. It opened as the world’s longest and as the only fixed cross-river connection between New York City in the south and Troy up north. At its peak, more than 3,500 passenger and freight train cars used the bridge on their journeys across the mighty Hudson River.

As the railroad age came to an end, so did the bridge’s utility. On May 8, 1974, a fire on the bridge’s wooden deck caused extensive damage to the railroad tracks. While the bridge was deemed structurally sound, the high cost to repair the deck wasn’t seen as a viable investment and put the bridge out of commission. Amid public discussion about what to do with the bridge, the river crossing was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, setting the stage for its second act.

During the 1990s, community support grew for a plan to transform the bridge into a multi-use pedestrian crossing. It took another 15 years before construction began, but with a combination of state and private funds, the Walkway Over the Hudson opened on a rainy October day in 2009 with the first of what would become many parades on the bridge.

Today, pedestrians, bikers and tourists use the Walkway as a unique way to enjoy the outdoors or cross the Hudson River. With community events, parades and access to the Empire State Trail, the walkway is a perfect example of how abandoned infrastructure can be transformed into a community resource.

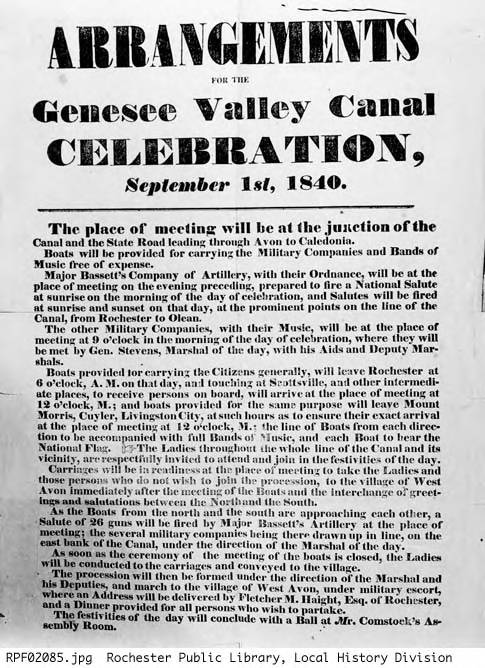

Genesee Valley Greenway State Park

A 90-mile open space corridor, the Genesee Valley Greenway runs north to south through more than a dozen western New York communities in five counties. Connecting the city of Rochester to the village of Cuba, the greenway links with several other trail systems and provides access to the Empire State Trail and Letchworth State Park. The trail is used by more than 100,000 residents each year in a continuation of its longstanding use as a canal and railroad right-of-way.

The first petitions for a canal on what is now the greenway were received before the Erie Canal was even complete! In 1823, community members identified the need for transportation infrastructure that connected Rochester to the Allegheny River. By 1836, New York State agreed. Construction began on the canal system was completed in 1862. A little more than a decade later, in 1878, the canal was abandoned, and the right-of-way sold to the Genesee Valley Canal Railroad. The transformation was complete in 1883, with passenger and freight rail service running between Rochester and Olean along track laid through the canal’s old towpaths. Rail service stopped in 1963, and the corridor was once again abandoned.

Around this time, New York State Parks was experimenting with new park concepts, including linear parks on old rail beds. While segments of the railway were purchased to expand Letchworth State Park, planners had a much bigger idea: a trail that would span the full distance of the former canal. In 1992, the first two miles of the trail would finally open, kickstarting a period of rapid development.

As more residents bought in to the plan, a public-private partnership was established between New York State and community organizations like the Friends of the Genesee Valley Greenway to complete the trail. Buy-in from the community is essential for any project, but especially when repurposing infrastructure — there are always various ideas on how unused land should be utilized. This is just one reason why New York State Parks hosts public meetings throughout project development.

By 2011, management of the trail was transferred to State Parks and the full trail integrated into the Parks system as Genesee Valley Greenway State Park. In 2020, new investments allowed the agency to resurface 7 miles of trail and repair culverts built for the canal. When the primary repairs were complete, leftover canal stone was used to construct picnic table bases, side tables and bike racks. Successfully repurposing grey space into green space, the trail is one of many examples of creating places to play from areas where people used to work.

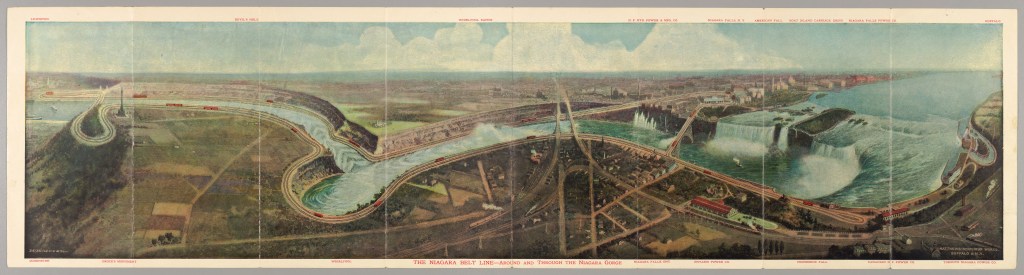

Niagara Gorge State Park Trails

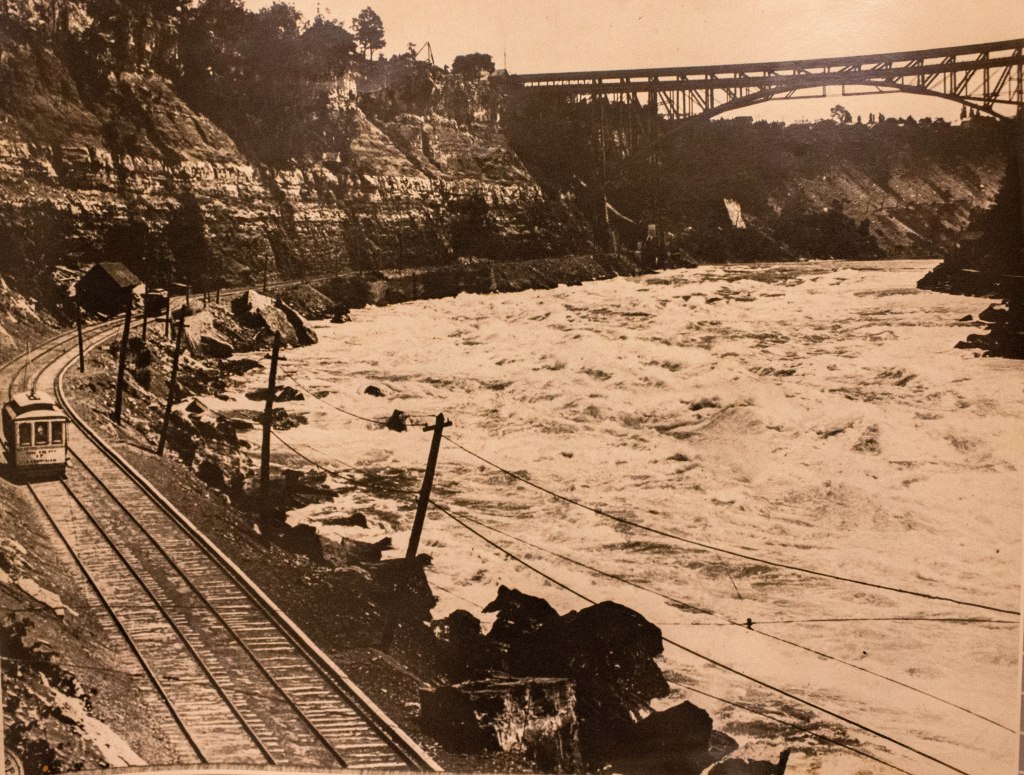

Comprised of nine unique trails, Niagara Gorge State Parks’ trail network connects Niagara Falls, DeVeaux Woods, Whirlpool, Devil’s Hole and Artpark State Parks. Several of these trails were once infrastructure, notably the Great Gorge Railway Trail (trail #4).

Before any of the trails existed, a trolley car system ran along the shores of the Niagara Gorge between Niagara Falls and Lewiston before crossing the border into Canada. Constructed in 1895, the Niagara Gorge Railroad served both commuters and tourists. The popular trolley line treated hundreds of thousands of passengers a year to impressive up-close views of the Whirlpool rapids before stopping at present-day Artpark State Park. In 1935, a major rockslide caused severe damage to the tracks and contributed to the railroad’s closure. Other factors included a decline in tourism amid the Great Depression, an increasing number of accidents, and the rise of car usage. While the trolley line was declining, recreational trails were on the rise.

In 1933, the first Niagara Gorge trails opened to visitors. Later expansions of the trail system included the creation of the Great Gorge Railway Trail which follows a portion of the railroad’s original right-of-way, stretching for roughly 1.25 miles between Niagara Falls and Whirlpool State Parks. Along the riverside trail, hikers can explore the roaring rapids and jagged rockface just like tourists of the past did, but this time at their own pace. Other trails along the gorge overlook the rail trail and provide bird’s-eye views of where this infrastructure once was.

The Niagara Gorge State Park trails are an important and popular resource for the surrounding community and international visitors alike who visit Niagara Falls State Park. These trails represent a return of naturally and historically significant places to public use, improving the lives of New Yorkers.

Gantry Plaza State Park

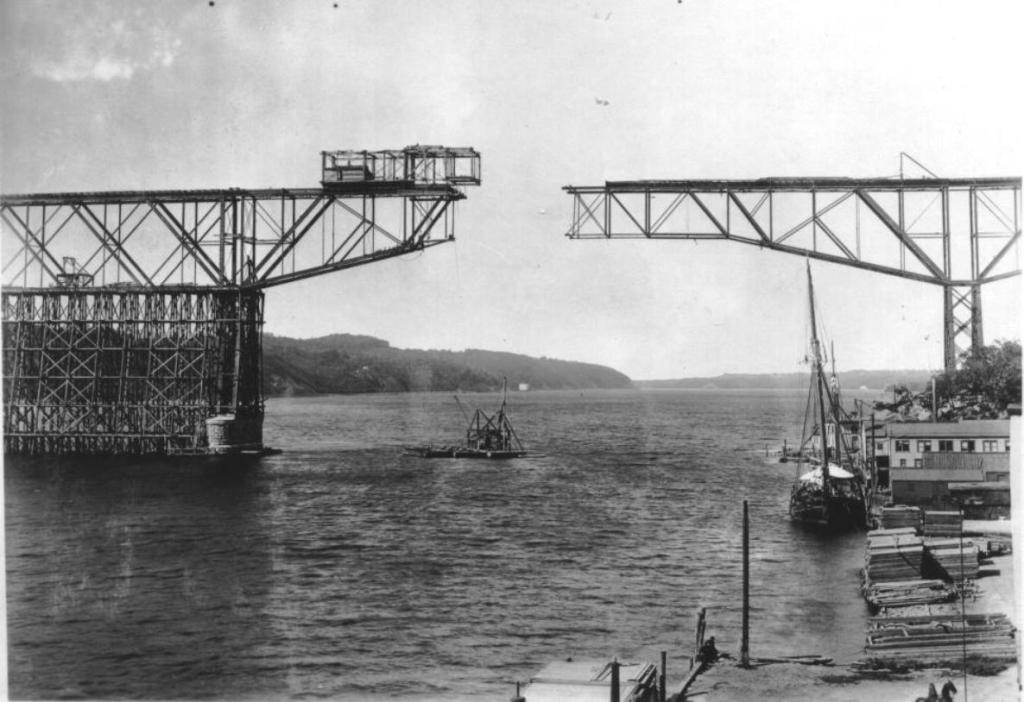

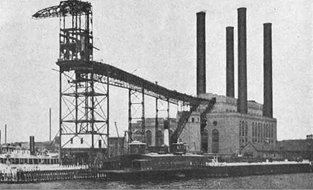

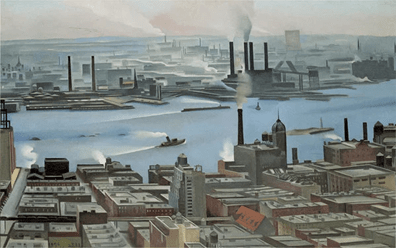

New York City was once the center of the industrial world. Heavy industry and transportation infrastructure like factories, railroads, barges and docks lined the shores of the East River. The Long Island City (LIC) gantries were a piece of this complicated infrastructure puzzle, keeping cargo flowing to and from the borough of Queens. Today, the gantries are the centerpiece of Gantry Plaza State Park.

As the 20th century began, Long Island City was the most industrialized neighborhood in the nation, partially due to its manufacturing and transportation role during the Civil War. As manufacturing grew, so did demand for transporting raw and completed goods. Railroads and ships kept the economy afloat and what is now a simple river crossing was once a complex operation. Trains crossing the East River from Queens to Manhattan had to be loaded onto barges and sailed from one side to the other. Getting these heavy train cars off of ships required massive cranes, known as gantries, to make the process fast and efficient.

In 1925, the Long Island Railroad constructed and opened a series of these gantries for their Hunters Point terminal. Capable of lifting 100-ton cars, the gantries were crucial for nearby factories. Like other pieces of transportation infrastructure, economic changes ultimately led to the decline of the gantries. In the 1970s, they were entirely abandoned by the railroads and left in disrepair. New York and the nation as a whole were in the mist of economic crisis — a city on the verge of bankruptcy and a nation in recession.

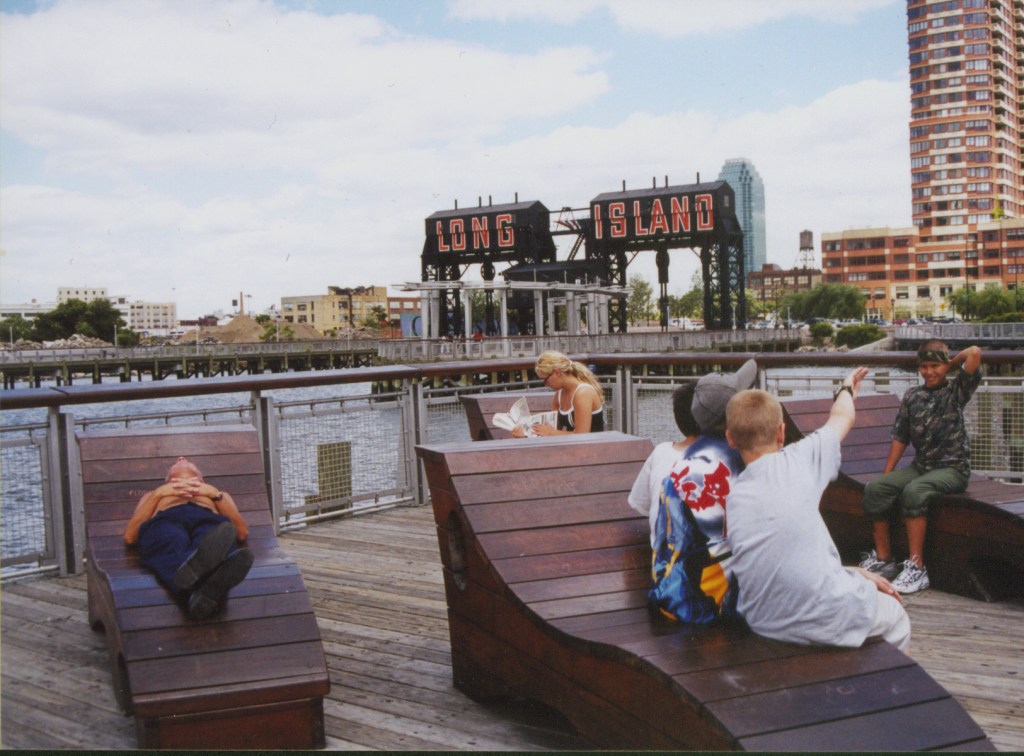

As tides turned and redevelopment of Long Island City began in the 1990s, a proposal for green space where the gantries stood would eventually morph into a state park. Named for the gantries that the park sought to preserve, Gantry Plaza State Park opened in 1997 as a place for residents of the growing LIC neighborhood to relax, play and learn about New York’s history. An iconic 120-foot-long sign from a Pepsi bottling plant was incorporated into the park, further adding to its industrial heritage.

Today, over three million people visit Gantry Plaza every year. The park is home to stunning views of midtown, popular fishing piers, playing fields and courts, and even a splash pad to cool residents off during the hot city summer months.

— Written by Jennifer Robilotto, Public Affairs Assistant