Tonight, the digital lights used to illuminate Niagara Falls will transform the thundering cascade into red, black, and green. Why?

There are three major threads in the answer: this date, June 19th; the colors red, black, and green; and our continued search for freedom. These threads are tightly woven into the fabric of New York’s history, and that of our country.

And one of the threads also carries a man who was born to a farm family in 1821 in a little hamlet called Joy in Wayne County, not far from Lake Ontario.

First the date, Juneteenth

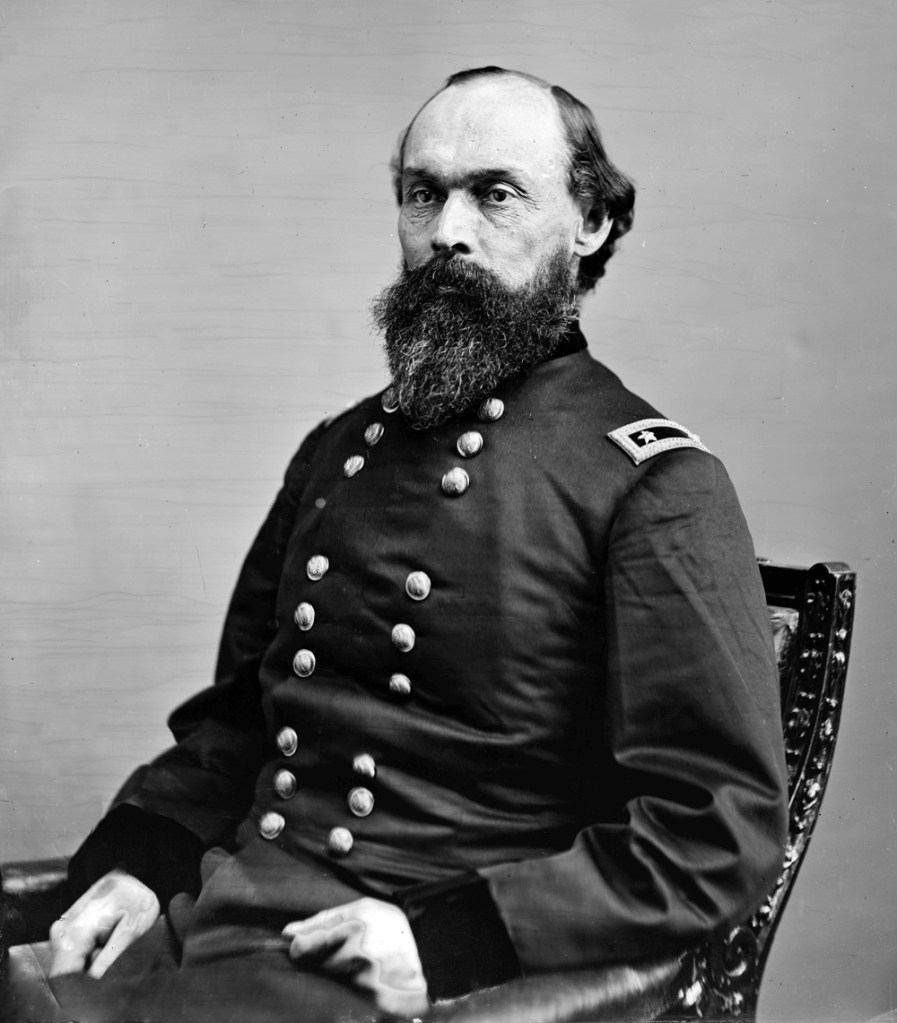

On June 19, 1865, in the Galveston, Texas, Major General Gordon Granger of the Union Army stood in front of a crowd of enslaved people of African descent and their enslavers, and declared the freedom established by the Emancipation Proclamation. Two years after President Lincoln issued that proclamation, those enslaved in Texas finally learned they were free.

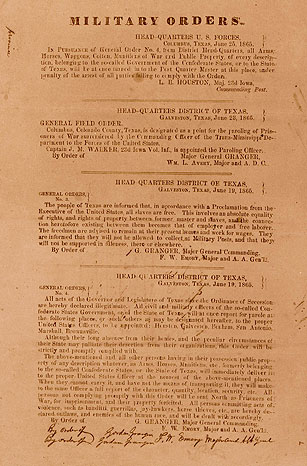

“The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

General Order # 3, as read publicly June 19, 1865 in Galveston by Major General Gordon Granger of the Union Army.

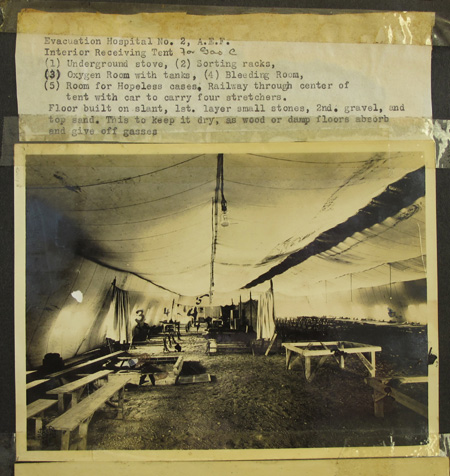

Major General Granger was a New Yorker from the hamlet of Joy, in the town of Sodus, Wayne County. A a young man, Granger taught for a time in the one-room schoolhouse on Preemption Road in Sodus. He then enrolled at the West Point military academy, graduating in 1845, going on to serve in the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1849.

Granger remained in the U.S. Army, with subsequent assignments in Oregon and Texas, and when the Civil War began in 1861, he was posted to Ohio. He later served in Missouri as part of Union forces that protected a key federal armory at St. Louis from falling into Confederate hands. In 1863, he played a decisive role in averting Union defeat the Battle of Chickamauga.

As war’s end, Granger was assigned to the newly-subdued Confederate state of Texas, where he read General Order #3 . That reading in Galveston became the basis of the African American community’s Juneteenth celebration, which was also known as Emancipation Day.

“In retrospect, it is very fitting that a man from Joy brought so much joy to a suppressed people in our country,” said Wayne County Historian Peter Evans.

Why did it take two years? Well…there are various tales about two earlier Union messengers, who traveled over land, but ultimately did not arrive in Texas. Granger entered the last Confederate state by water, with a fully loaded army. Texas is a big place, and held many of the enslaved.

Even though Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered on May 9 in Virginia, it took time for word to get out that the war was essentially over. Major General Granger and army moved from place to place after Galveston, reading General Order #3 repeatedly, setting off much rejoicing from the formerly enslaved, as well as variations of the same question, ‘What now?’

Coming to terms with freedom was not an easy task for those newly freed, or for those who had enslaved them. Where were the freedmen to go? What were they to do? Who was going to bring in the crops, cook the meals, care for the children? What had been ‘normal’ life was changed in an instant. A new reality now existed but what did it mean?

Theirs was a position much like what we find ourselves in today. One minute things are moving along pretty much as they had been the day before, our routines keeping everyone’s life flowing, then suddenly wham! We’re faced with something we don’t quite understand and the big question ‘What now?’

Although people point to June 19th as the exact catalytic moment for celebration, it is the process of coming to terms with freedom that is the driving force behind the celebration of Juneteenth in the 21st century. Spreading the word about freedom and defining what that meant took time and it is something we are still grappling with today.

The Colors: Red, Black, and Green

On August 13, 1920, at Madison Square Garden, New York City, members of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) adopted the Pan-African flag, also known as the UNIA flag, and the Black Liberation flag as ‘the’ flag for black people across the diaspora and in Africa. The organization, founded by Marcus Garvey, was composed of members from around the globe. The flag was created in response to a popular 1920 song, “Every Race Has a Flag but the Coon.”

In 1921 the UNIA published the Universal Negro Catechism, which outlined the meaning of the colors of the flag. “Red is the color of the blood which men must shed for their redemption and liberty; black is the color of the noble and distinguished race to which we belong; green is the color of the luxuriant vegetation of our Motherland. “

At a time when racism was living in our country under the title of Jim Crow, and segregation was real even in New York, African Americans were working to improve their circumstances in every way possible. The UNIA flag took flight and the colors were embraced. They were seen throughout the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Power Movement, and various black liberation movements around the world. They appeared everywhere and are also the colors of the candles used during Kwanzaa. They are the colors which symbolize to most African Americans and others who have supported their fight for human rights that the struggle was and remains real and the work continues.

Although in 1997 the National Juneteenth Celebration Foundation (NJCF) created a flag to honor the day, we have chosen at this pivotal time in our Nation’s history to use the colors most New Yorkers would recognize as those representing the continued struggle for freedom, dignity and human rights by African Americans and members of the African diaspora: the red, black, and green of the Black Liberation flag.

On Wednesday, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that Juneteenth will now be an official state holiday.

“Friday is Juneteenth – a day to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States – and it’s a day that is especially relevant in this moment in history,” Governor Cuomo said. “Although slavery ended over 150 years ago, there has still been rampant, systemic discrimination and injustice in this state and this nation, and we have been working to enact real reforms to address these inequalities. I am going to issue an Executive Order recognizing Juneteenth as a holiday for state employees and I’ll propose legislation next year to make it an official state holiday so New Yorkers can use this day to reflect on all the changes we still need to make to create a more fair, just and equal society.”

Juneteenth is now recognized as a holiday or special day of observance by 47 states, with New York first marking it as a day of observance in 2004.

Freedom in Our Time

At the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, we continue to work to bring forward the under-told stories of the lives, cultures, and work of Africans and African Americans who helped to build New York and our Nation. The thread of their lives must be woven back into the whole cloth of our State’s history.

We do so by sharing with you the entire historic timeline. From the arrival of the first Africans who were enslaved in New Netherland in 1625 to 20th century locations that mark important cultural shifts and points of pride from around our State.

Exhibits like the Dishonorable Trade at Crailo State Historic Site help us to understand how an empire was laid on the foundation of the global slave trade. We celebrate the preservation of African culture In New York, during the years of enslavement at Pinkster.

Reviving A Dutch Holiday with African Flavor

As spring moves toward summer, we are in the time of an historic celebration dating to New York’s colonial era known as Pinkster – the Dutch word for the religious holiday of Pentecost. Pinkster was a three- to five-day celebration beginning the Monday following Pentecost Sunday held in Dutch Colonial New Netherland and later New…

In the Adirondacks, we operate the John Brown Farm State Historic Site, at the home of a New York abolitionist who took up arms in a bid to liberate slaves in the South.

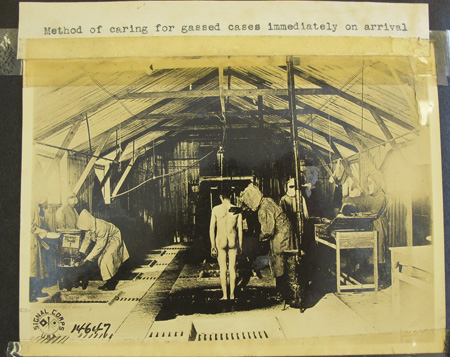

We honor the dedication of service given by men of African descent, first to the colony of New York and later to the United States at many of our military parks, from New Windsor Cantonment to Fort Ontario. Remembering the enslaved and free who served in the Revolutionary War all the way to the Harlem Hell Fighters during World War I.

We bring to light the work of men just trying to make a living during the Great Depression, through their employment in the Civilian Conservation Corps.

A Legacy of Strength

During the 1930s when racial segregation and Jim Crow held sway over much of America, there was a Depression-era federal public works unit where African-Americans, not whites, were in command. And it was here in New York State Parks. To combat rampant unemployment among young men, President Franklin Roosevelt had created the Civilian Conservation Corps…

The work and commitment of women like Sojourner Truth and Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman to run for President and the inspiration for the largest State Park in New York City. All while saving important landmarks connected to Black culture across 200 hundred years of State history.

Wonderful places right in our own neighborhoods like the historic Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered “The American Dream” address, to the Colored Musicians Club in Buffalo, through the State’s Registry of Historic Landmarks and supporting them as they seek national recognition. We do this, not only for the African American community, but for all the communities that have helped to build New York.

Our history has always been blended. Henry Hudson did not find an empty land, but one filled with people and culture; the Munsee, the Wappingers and Lenape among them, to this more was added. The formation has been forward moving, but not always easily.

New York is and has been one of the main gateways through which people have entered this country and continue to do so. It has also been a way towards freedom as thousands passed through on the Underground Railroad, heading north to Canada. Aiming for Niagara Falls and the freedom that lay just on the other side.

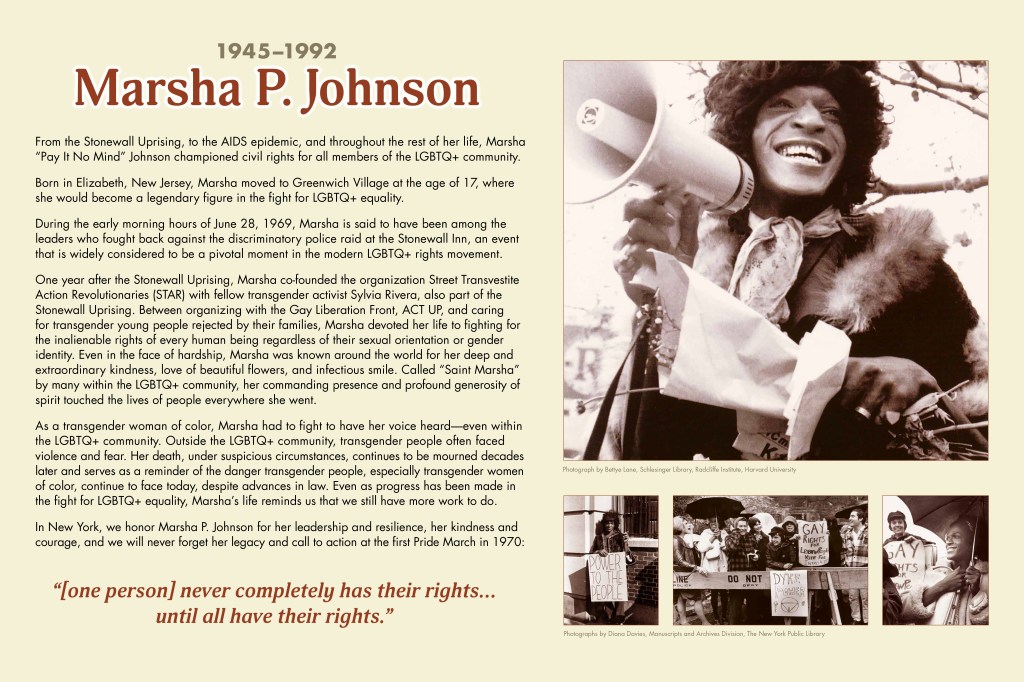

As we continue to come to terms with freedom, we invited you to explore the rich stories of others who have also found themselves struggling with defining what those terms meant to them. Narratives to be found at our parks and historic sites, online and in person. These stories, from those of the Native Peoples at Ganondagan to the newly renamed Marsha P. Johnson State Park cross over and through all the cultures and timelines that create the vibrancy of New York.

And, what became of Gordon Granger? A year after he read General Order #3, he was reassigned as an officer in the 25th Infantry Regiment, which was of four racially segregated regiments made up of African American enlisted men and white officers.

These four regiments became known collectively as the “Buffalo Soldiers,” which was the nickname given by Native Americans to African American soldiers who fought in the Indian Wars of the west.

With the Statue of Liberty at one end and Niagara Falls at the other we offer this lighting of Niagara Falls as a symbol of our continued willingness to be inclusive and open, even amidst struggle and pain.

Cover Photo- Niagara Falls at Niagara Falls State Park, by New York State Parks. All photos by NYS Parks unless otherwise credited.

Post by Lavada Nahon, Interpreter of African American History, Bureau of Historic Sites, NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation