Established in 1985, the New York Natural Heritage Program is a partnership between the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry and NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. The program’s mission is to determine the location and status of New York’s plants, animals, and ecological communities and provide this information to public agencies and scientific and educational institutions to facilitate conservation. Today, they count multiple non-profits, local governments, federal institutions, and state agencies among their partners — including New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Sites. You may have heard about their long-term firefly study at several of our parks. Ecologist Julie Lundgren shares more highlights from their year of work in New York State Parks.

Continue reading A Year in the Field With the NY Natural Heritage ProgramTag Archives: New York Natural Heritage Program

Moths: Friend and Foe

What’s your first feeling when you hear the word moth: irritation or wonder? Anyone who’s gotten an unpleasant surprise when taking winter wools out of storage will agree that moths can be a menace to clothing and bedding. But at the same time, the varied species of moths lend beauty and majesty to nights outdoors and play an important role in our ecosystem.

As a textile conservator, Sarah Stevens works with historic site staff to prevent moth damage and respond to it when it occurs. As a wildlife biologist, Kelsey Ruffino facilitates the study of the moth population in New York State parks and ensures it has the support that they need to thrive. Both share their professional perspectives on these winged insects.

Continue reading Moths: Friend and FoeSpotted Turtles on the Move For Spring!

While we must stay put this season to help protect ourselves and those we love, other creatures here in New York are making their seasonal spring migrations.

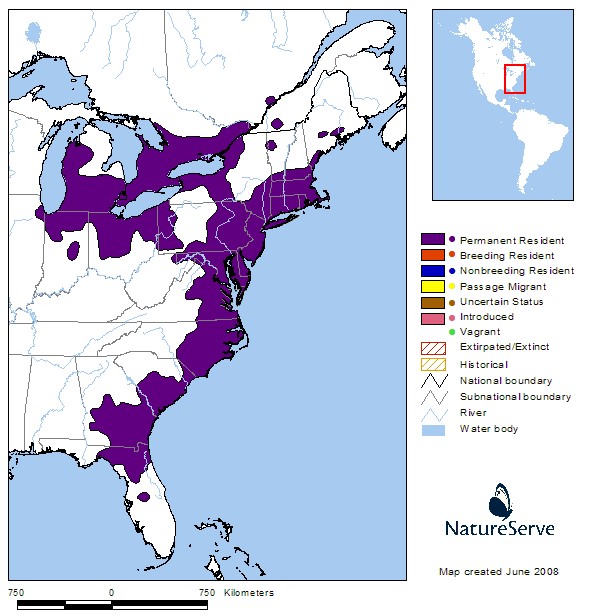

Among those are spotted turtles. These small, attractive reptiles can be found throughout much of New York in the Hudson Valley, on Long Island, and in the plains of western and central New York. They generally emerge from their winter hideaways in March or early April (Gibbs et al. 2007).

Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) are more tolerant of cold water and are one of the first aquatic turtles to become active; you might see them basking throughout winter depending on temperatures. Early spring is the best time of the year to spot these turtles. There is ample food with salamanders and frogs laying their eggs in vernal pools (Beaudry et al. 2009). They will also eat aquatic insects and other invertebrates such as slugs, worms, and snails (Gibbs et al. 2007). When looking for turtles, keep an eye out for them basking in small pools, marshes, and other wetlands on rocks, logs, and along the shoreline.

The reason these turtles are called spotted turtles is obvious when you see one – the black carapace (upper shell) and skin are covered in small, round yellow dots. This color pattern could reduce the turtle’s likelihood of capture since it resembles the floating duckweed present in many frequently used habitats. This camouflaging pattern makes it difficult to find spotted turtles when they are in the water.

Spotted turtles are thought to be declining throughout their range, and there are several threats that may be contributing to the decline. These turtles can experience high mortality from crossing roads as they move between wetlands during the spring and in search of nesting and upland summer locations. (Beaudry et al. 2009, Ernst and Lovich 2009).

Nesting female mortality is especially bad for spotted turtle populations, since it can take 10-15 years before a female is old enough to reproduce.

Spotted turtles can live over 40 years, so once a female reaches reproductive age it has many years of egg laying ahead. Turtle eggs and juveniles have a high mortality rate, so it is important to keep these older females around to keep producing eggs, only a small fraction of which will reach adulthood.

One important habitat requirement of spotted turtles is relatively shallow, clear, and clean water with a soft, muddy bottom (Gibbs et al. 2007, Ernst and Lovich 2009). They will spend most of the spring within these wetland habitats, until females travel to find a nesting site in early June.

Spotted turtles will practice estivation, a period of dormancy during high temperatures, by retreating into the muck at the bottom of wetlands, into muskrat burrows, or under vegetation in the surrounding uplands during the warm summer months when many wetlands are drying up (Gibbs et al. 2007, Ernst and Lovich 2009, Joyal et al. 2001, Milam and Melvin 2001).

Other threats spotted turtles face are collection for the pet trade, habitat loss and fragmentation, invasive plants, and predators (Ernst and Lovich 2009, NYSDEC 2020). Spotted turtles are a target for the commercial pet trade (CITES 2013) due to their small size and attractive coloring.

Habitat loss and invasive plants encroaching on wetland habitats can reduce the amount of suitable habitat these turtles have available to use throughout the year. They need upland buffers around wetland habitats for nesting, movement between wetlands, and summer estivation (Milam and Melvin 2001), and these habitats are frequently fragmented by development and roads.

What can you do to help protect these cryptic little turtles? If you are lucky enough to catch a glimpse of a spotted turtle in the wild, admire it from afar and leave it undisturbed. All native species of turtles in New York are protected and cannot be collected without a permit.

If you happen to see one crossing the road, pull over in a safe place and help it along. Make sure to move the turtle to the side of the road that it was facing, otherwise it will just turn around and cross the road again!

Cover Photo- Wikipedia Commons

Post by Ashley Ballou, Zoologist, NY Natural Heritage Program

References

https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/44388.html

https://guides.nynhp.org/spotted-turtle/

Ernst. C. H., and J. E. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Second edition, revised and updated. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland. xii + 827 pp.

Beaudry, Frederic, Phillip G. deMaynadier, and Malcolm L. Hunter Jr. 2009. Seasonally dynamic habitat use by spotted (Clemmys guttata) and Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) in Maine. Journal of Herpetology 43:636-645.

Gibbs, J.P., A.R. Breisch, P.K. Ducey, G. Johnson, J.L. Behler, and R.C. Bothner. 2007. The amphibians and reptiles of New York State. Oxford University Press, NY.

Joyal, Lisa A., Mark McCollough, and Malcolm L. Hunter Jr. 2001. Landscape ecology approaches to wetlands species conservation: A case study of two turtle species in souther Maine. Conservation Biology. 15(6): 1755-1762.

Milam, J. C., and S. M. Melvin. 2001. Density, habitat use, movements, and conservation of spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) in Massachusetts. Journal of Herpetology 35:418-427.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2020. Spotted turtle fact sheet. Available https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/7150.html. (Data accessed March 2020).

In Search of the Early Bloomers

The ground is thawing out and the skunk cabbage is up – it’s time to start searching for the purple rock cress (Cardamine douglassii), a state-threatened plant. You may also find its more common cousins, all members of the mustard family – yes, like the mustard you eat, but with white to pink flowers rather than yellow. Moist woodlands with oak, hickory, and maple are a good place to look, including forests with vernal (spring) pools. Perhaps you might be out looking for frogs and salamanders around this time of year, if so -keep an eye out for these early flowering plants, too. Woodland rock cresses tend to be small, only about 3 to 8 inches tall, so they are easy to miss. If you see some patches of green that are not mosses or mounds of sedges (grass-like plants), take a closer look – you may be rewarded with some delicate flowers.

Forests with vernal pools or small streams or wetlands are a good place to look for these cresses.

Look for patches of green on the forest floor and take a closer look. You might find some flowers.

A close-up of that woodland patch of green reveals this beautiful plant, the cut-leaved rock cress or cut-leaved toothwort (Cardamine concatenata), a common woodland wildflower. This used to go by the name Cardamine laciniata or Dentaria laciniata. It is easy to identify by its lacy leaves that look a bit like bird tracks.

Several of the other rock cresses, including the purple rock cress, have smaller and less complex leaves like this or just small roundish leaves on the stem or at the base of the plant (see in background).

Spring cress (Cardamine bulbosa) is another common cress that blooms very early. The flowers can range from white to pink, and it can be hard to tell this apart from the rare purple rock cress. Note that all of the flowers in the mustard family have 4 petals regardless of their color.

Here is the rare Cardamine douglassii, so similar to the spring cress above. One has to consult the botanical keys in order to figure out which species you have. Some trout lilies are coming up too (leaves at upper left).

NY Natural Heritage and State Parks staff discovered two new locations for this rare species in State Parks in the past few years and hope that more are found in this year’s early spring surveys.

The flowers of the cresses don’t last long, only until the trees leaf out. Once in fruit, you can still recognize them by their elongate seed pods, which give rise to yet another common name for this group of plants, the “rockets”.

Post written by Julie Lundgren, NY Natural Heritage Program

Featured image by Kyle Webster, State Parks

NY Natural Heritage Program is affiliated with SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF) and works in close partnership with NYS Parks and NYS DEC. NYNHP conducts many kinds of surveys and studies to provide guidance and tools for conservation of native biodiversity across New York State.

Recommended references for identifying the rock cresses:

https://gobotany.newenglandwild.org/genus/cardamine/

Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide by Lawrence Newcomb. Little, Brown and Co. 1989.

For more information:

NY Flora Atlas Purple Rock Cress

NYNHP Conservation Guides Purple Rock Cress