If you haven’t noticed, New York’s ash trees have been struggling lately. Over the last few years, they have been rapidly dying due to a little iridescently green insect: the emerald ash borer (EAB).

An invasive beetle native to parts of Asia and Russia, EAB was first discovered in New York in Cattaraugus County in 2009. It has since spread to 55 of New York’s 62 counties, decimating once thriving ash populations.

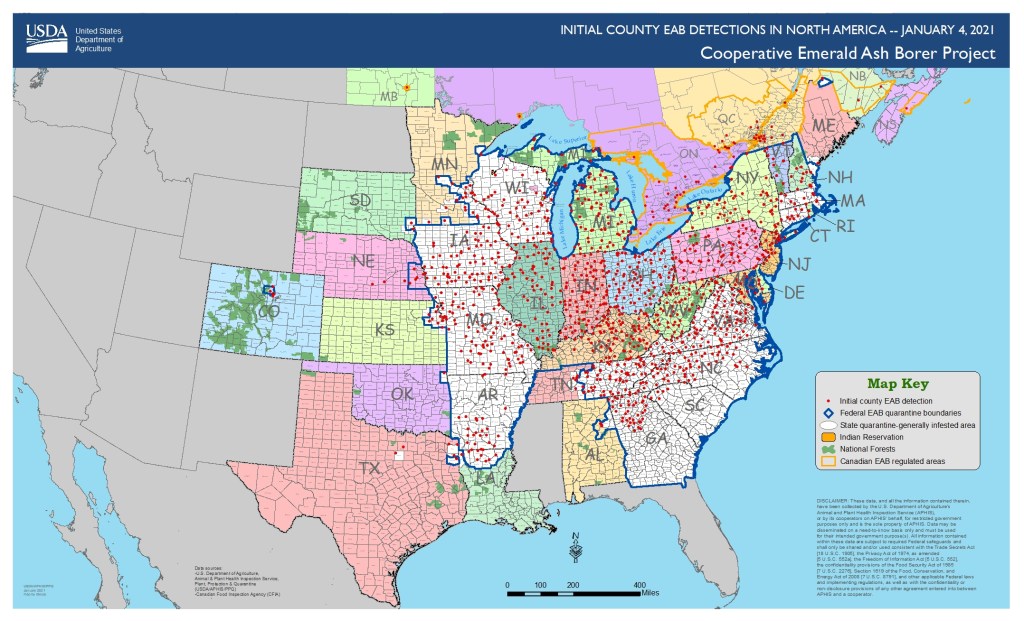

Since its discovery in southeast Michigan in 2002, EAB has spread into 35 states and the District of Columbia, killing tens of millions of ash trees in their wake.

Emerald ash borers lay eggs between bark layers and in bark crevices on ash trees. Upon hatching, the larvae burrow through the bark and begin to feed on the tree’s living parts: the phloem and sapwood. The larval feeding creates galleries, which cut off the movement of nutrients throughout the tree. Eventually, as the infestation grows, the tree’s system of nutrient transport ceases to function, and the tree slowly starves and dies.

Ash trees are important for so many reasons. They provide cool shade in the summer heat, provide habitat for wildlife, and are a valuable source of timber and firewood. When large ash die, however, they can pose serious safety risks. Dead and dying trees often bring down powerlines along the road and cause blackouts.

In addition, many trails, campgrounds, parking lots and playgrounds are surrounded by ash that, once infested, become hazard trees that require removal. Parks’ staff must constantly monitor public use areas for the presence of dying trees that may pose a risk to patrons.

The fight to conserve ash has been an uphill battle. While pesticide treatments work, they only last a year or two before reapplication is necessary and also are too expensive to use everywhere. Statewide quarantines and public education have helped slow the spread, but these little beetles can fly over a mile and lay up to 200 eggs in a lifetime, making containment difficult.

You may be thinking “what can be done?!” Well with National Invasive Species Awareness Week coming May 17-23, an update from State Parks is timely.

Luckily, we may finally have a cost-effective, sustainable, and chemical-free solution to the problem. For the second year in a row, the state Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) are partnering to release three species of predatory wasps – known ecologically as biological controls or parasitoids – to battle EAB in select state parks.

These tiny warriors are heavily studied little predators from the EAB’s home countries which prey only on these beetles and pose no risk to our native ecosystem. (And don’t worry. These wasps don’t sting and are no threat to people).

The females of these species attack ash borers in the early stages of their life cycle. These three wasps were chosen because they each have slightly different ways of tackling EAB, making them a more effective as a group.

Here, let’s meet our winged team.

Tetrastichus planipennisi females lay eggs inside of EAB larvae, where the parasitoid larvae grow and eventually kill their host. They are used to protect smaller ash trees in particular, and they originate in China.

Oobius agrili lay eggs inside EAB eggs, where the parasitic wasp larvae hatch, grow, and kill the host EAB egg. These wasps are all female, so they reproduce asexually. They also originate in China.

Spathius galinae lay eggs outside of EAB larvae; when they hatch, Spathius feed on the EAB larvae, killing it. These wasps are best at helping larger ash trees, and are collected in the Russian Far East.

Last year, 11 State Parks received about 40,000 Tetrastichus wasps: Rockland Lake in Rockland County; Harriman and Bear Mountain in Rockland and Orange counties; Minekill in Schoharie County; Beaver Island and Buckhorn Island in Erie County; Clay Pit Ponds in Staten Island; Lakeside Beach in Orleans County; Golden Hill in Niagara County; Southwick Beach in Jefferson County; and Point Au Roche in Clinton County.

Starting this month, Jacques Cartier State Park in St. Lawrence County and Ganondagan State Historic Site in Ontario County will be added to that list. All three wasp species will be deployed, with an expected total of more than 50,000 wasps. All the wasps used are reared in a lab in Michigan, where they are shipped to New York and other states where USDA is coordinating its EAB biocontrol program.

For the wasps to be successful here, they need to find the beetle in its early life stages. In New York, the emerald ash borer generally begins to lay eggs in the summer; however, many larvae overwinter inside of ash trees, and are thus readily available as food for the parasitoids in the spring.

Parks staff introduces the wasps into infested ash trees through three methods:

- Ash bolts are small sections of ash (think small ash logs slightly larger than cans of soup) that house mature parasitoid larvae. They are attached to infested ash trees using twine or zip ties. When the larvae mature, they leave the bolts and find EAB larvae to feed on within the ash stand.

- Plastic cups containing adult parasitoids arrive on-site ready for distribution. The cups simply need to be opened, inverted and tapped gently against the trunks of infested trees.

- Oobinators are used less frequently and only for the delivery of Oobius agrili. They are small, plastic pill bottles with a screen over the open end that can be attached to trees with zip ties or twine. They contain a sheet of paper with parasitized EAB eggs. Once mature, Oobius will hatch and escape through the screen.

While out exploring NYS Parks, you may see these “ash bolts” or “Oobinators” attached to trees. They are often marked with flagging for easy identification. While it may be tempting to try to get a closer look at these woodland wasp homes, it is important to let the parasitoids grow and feed uninterrupted, to give them the best possible chance of survival.

While parasitoid releases may be new to New York State Parks, USDA has been conducting releases throughout the country for several years. Subsequent studies indicate that that wasps are surviving and are feeding on the EAB.

Studies have also shown that the Tetrastichus wasps in particular can eliminate up to 85 percent of EAB larvae in ash saplings. (Duane et al., 2017)

These are promising results which suggest if parasitoid wasps can be reared in abundance, they may offer crucial protection to the next generation of ash trees. It is important to keep in mind, however, that success will not happen overnight. Wasps need to find enough EAB to build up their populations to sustainable levels and it takes time to see results, even if wasp populations are doing well. Parasitoids also will most likely not save most larger ash, but they can help manage EAB populations so smaller ash trees can have a chance grow and hopefully reproduce.

Parks is thrilled to partner with USDA in this important endeavor to protect our forests. You also can join in the effort by reporting emerald ash borer sightings or suspected damage to the iMapInvasives website or smartphone app. There is also a USDA online reporting form here.

Also, help stem the spread of EAB and other invasive forest pests by following state regulations that control the movement of untreated firewood, which can carry these invasive hitchhikers.

- Untreated firewood may not be imported into NY from any other state or country.

- Untreated firewood grown in NY may not be transported more than 50 miles (linear distance) from its source or origin unless it has been heat-treated to 71° C (160° F) for 75 minutes.

- When transporting firewood, the following documentation is required:

- If transporting untreated firewood cut for personal use (i.e. not for sale) you must fill out a Self-Issued Certificate of Origin (PDF).

- If purchasing and transporting untreated firewood, it must have a receipt or label that identifies the firewood source. NOTE! Source is sometimes, but not always, the same as where it was purchased. Consumers need to use the source to determine how far the firewood may be transported.

- If purchasing and transporting heat-treated firewood, it must have a receipt or label that says, “New York Approved Heat-Treated Firewood/Pest Free”. This is the producers’ declaration that the firewood meets New York’s heat-treatment requirements. Most “kiln-drying” processes meet the standard, but not all, so it is important to look for the appropriate label. Heat-treated firewood may be moved unrestricted.

Find out if your destination is within the 50-mile movement limit by using this interactive map from the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

Finally, if you encounter evidence of biocontrol release sites while out on State Parks trails, know that you are in the presence of these wasp warriors, engaged in a battle to save our beloved ash trees.

Above, Parks staff hang ash bolts and record release data used by USDA to measure the effectiveness of the project to combat the Emerald Ash Borer.

Cover shot – Emerald Ash Borer (Original Artwork – Juliet Linzmeier, Student Conservation Association member with NYS Parks) All other photo credited to NYS Parks unless otherwise noted.

Post by Sarah Travalio, Terrestrial Invasive Species and Biocontrol Coordinator, New York State Parks

Here are other easy tips that can make a big difference in helping stop the spread of all invasives:

- Clean, drain, and dry your watercraft and gear thoroughly to stop the spread of aquatic organisms.

- Plant only non-invasive plants in your garden, or even better, plant native plants. You can use the New York Flora Atlas to check which plants are native to New York.

- Clean your boots or your bike tires at the trailhead after hitting the trail – seeds of invasive plants can get stuck on your boots, clothes, or tires. You don’t want invasives in your yard or your other favorite hiking spots.

- Get involved – volunteer to help protect your local natural areas, join your local PRISM (Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management) to stay informed, or become a citizen scientist by using iMapInvasives to report infestations of invasive species right from your smartphone.

Interested in taking a deep dive into research on the parasitoid battle against the EAB? Check out these scientific studies:

Jian J. Duan, Leah S. Bauer, Roy G. Van Driesche, Emerald ash borer biocontrol in ash saplings: The potential for early stage recovery of North American ash trees, Forest Ecology and Management, Volume 394, 2017, Pages 64-72, ISSN 0378-1127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.03.024.

Duan, Jian J., Leah S. Bauer, Kristopher J. Abell, Michael D. Ulyshen, and Roy G. Van Driesche. “Population dynamics of an invasive forest insect and associated natural enemies in the aftermath of invasion: implications for biological control.” Journal of Applied Ecology 52, no. 5 (2015): 1246-1254. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12485

Jian J Duan, Roy G Van Driesche, Ryan S Crandall, Jonathan M Schmude, Claire E Rutledge, Benjamin H Slager, Juli R Gould, Joseph S Elkinton, Establishment and Early Impact of Spathius galinae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) on Emerald Ash Borer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in the Northeastern United States, Journal of Economic Entomology, Volume 112, Issue 5, October 2019, Pages 2121–2130, https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toz159

Are these wasps available for private land? I own timber in Cattaraugus county where the EAB was first found.

We are checking now into that possibility. Meanwhile, here is a link to the USDA program that manages the wasps. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/!ut/p/z0/fYzBCsIwEAW_JsewiUhJj9VDQMSjtHsJWxt0bUjTJoj-vaXePc6bxwBCCxjpxXcqPEUKK3dYuYs-WmX2-mxqo1RT28NVa7uztoIT4P_DWuDnPGMDeJti8e8CLaUHZ7dhLC5wv9DyEWqbZfK5ZElxkANnT9lnoVKgWH5GKE89pBG7L7gEPgI!/