Many buildings and features built for New York state parks during the 1930s mimicked the natural environment. In the period after World War II, this rustic style started sharing space with more modern designs.

One of the busiest construction periods of the New York State Parks system was during the 1950s and 1960s, when park planners were expecting to welcome record numbers of visitors. You can learn more about that history in our Blazing a Trail timeline project. But, for a deeper dive into the architecture leading up to that era, keep reading…

From Rustic to Modern

After World War II, the taste for rustic architecture that defined the interwar period of New York’s state park design began to wane. This also happened across the National Park Service system, which fully embraced modern architecture in the mid-1950s.

There were many reasons for rustic architecture’s declining popularity:

- loss of federal labor, which had been available through programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps;

- emergence of more cost-effective construction materials, such as concrete and steel;

- need to rapidly and economically build out parks that had languished during World War II.

Underlying these developments was a major paradigm shift in American architecture. The newly popular European Modernism and International Styles rejected traditional forms, styles, and ornamentation. These styles favored geometric forms, structural clarity, and modern materials. The circumstances of the postwar period also aligned well with architectural modernism; rustic architecture was more costly, more labor-intensive, and required specialized work to maintain.

Nevertheless, strains of the rustic tradition carried into the postwar era, particularly in the state parks with an established rustic theme. A more streamlined and decidedly modern design program emerged in the 1950s before fully flowering in the Rockefeller period of the 1960s, when modernism found full expression in the state park system.

Subtle Shifts in Rustic Designs

At state parks such as Letchworth State Park and Hamlin Beach State Park, architectural rusticity already defined the built environment, and carried into the postwar era. Yet subtle differences distinguished the prewar rustic mode from postwar styles.

At Letchworth, where the park landscape has remarkable rustic buildings, circulation paths, and wayside features, buildings like the 1951 restroom at Inspiration Point exhibit the scale, traditional gable-roofed form, and stone exterior typical of earlier work. However, the nature of the stonework sets it apart from prewar work.

(Terminology check: A gable roof is a roof with two sloping sides that meet at a peak. The triangular end is called a gable.)

Identical stonework, consisting of a matrix of coursed, rectangular-shaped stone interspersed with larger stones that rise multiple courses is also found on the 1959 contact station at the park’s Portageville entrance.

(Terminology check: A course is a continuous row of similar materials, like the horizontal layers of a wall).

At Hamlin Beach, regionally quarried Medina sandstone was used extensively for the park’s rustic architecture. That tradition continued into the postwar period, as seen in the 1951 contact station. Despite its natural material palette of rough-hewn sandstone walls and slate-shingle roofing, it exhibits a streamlined profile and glass-enclosed contact booths indicative of contemporary trends.

Blended Styles

John Boyd Thacher State Park witnessed considerable development during the 1950s due to increasing visitation.

Buildings constructed during this era at Thacher represent a convergence of rustic and modern design impulses. They include the Glen Doone picnic shelter (ca. 1950), which features paired bluestone piers that sustain large horizontal beams of glue-laminate construction supporting the pavilion’s flat, overhanging roof. Wood “glulam” construction was a commonly used building technique for state park buildings in the postwar era.

(Terminology check: In architecture, piers are vertical support structures.)

Horseshoe 1 pavilion (original construction ca. 1955), John Boyd Thacher State Park.

The Horseshoe 1 pavilion (ca. 1955) features the same general design as the Glen Doone, but includes wood panels with a herringbone motif between the sets of masonry piers. Both shelters are expressive of park postwar design, in which existing rustic principles were informed by modern tendencies.

Glen Doone concession building (original construction c. 1950), John Boyd Thacher State Park.

Also notable is the Glen Doone concession building (c. 1950), built with a terraced patio of interlocking geometric forms. The building’s shape recalls a carousel, with a round central mass from which extends a broad 12-sided roof, providing shelter for the benches ringing the feature’s circular concrete base. The deeply overhanging roof appears cantilevered, but bears on slender circular metal supports. Unlike the picnic shelters, restrooms, and other buildings erected during this era, the concession building shows little in the way of rustic sentiment or treatment.

(Terminology check: Something described as cantilevered is referring to a projecting structural element that is only supported on one end).

Pools and Bathhouses

As the state park system continued to develop in the postwar era, buildings and features accommodating an expanding range of functions were needed to meet the surge of visitation that followed the end of the war.

Among these were pool complexes, such as at James Baird State Park in the Taconic region. While the swimming pool no longer exists, the complex’s keynote feature—the bathhouse (1950)—remains. Note the building’s long, low-slung profile and material palette that skillfully integrates bluestone, slate, wood, and brick elements. Interior features such as salt-glazed tile walls and clerestory windows provided a clean modern feel.

(Terminology check: Clerestory windows are placed high on a wall– above eye level – to let in natural light and/or fresh air).

Understated in overall effect, with well-scaled individual features that form a cohesive whole, it reveals an increasingly modern disposition.

Many of the larger buildings erected in state parks during this era were designed by outside architectural firms. The Baird bathhouse is a notable early work of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, a pioneer of modern architecture and skyscraper design in the United States.

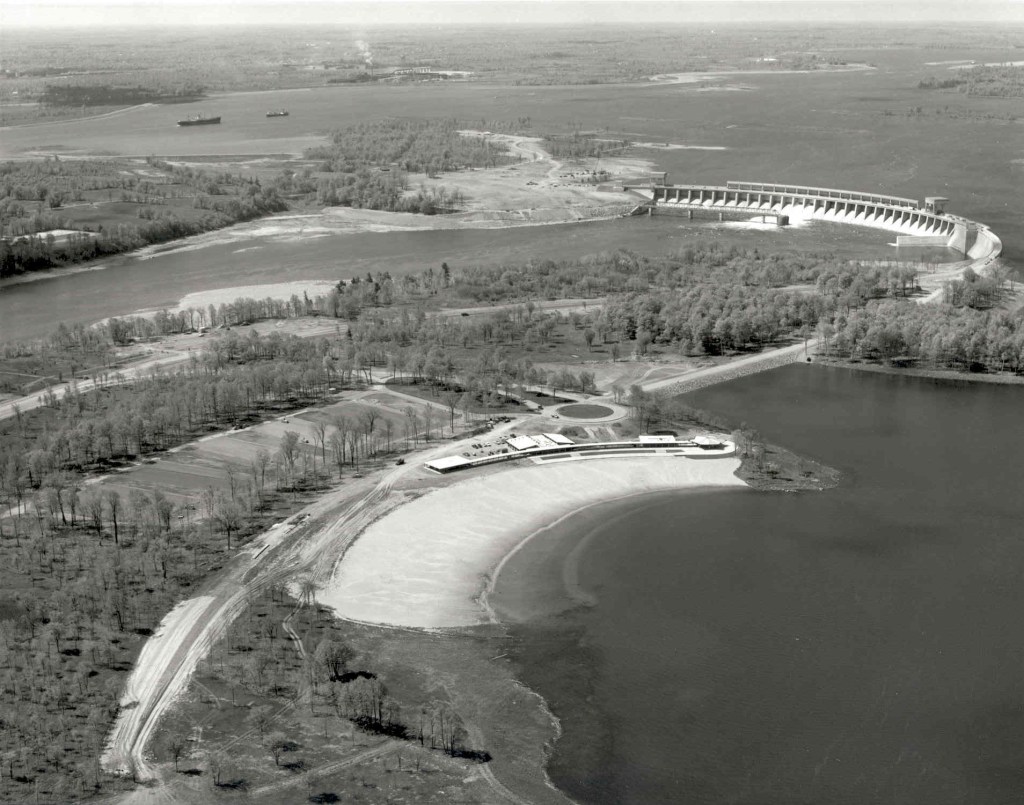

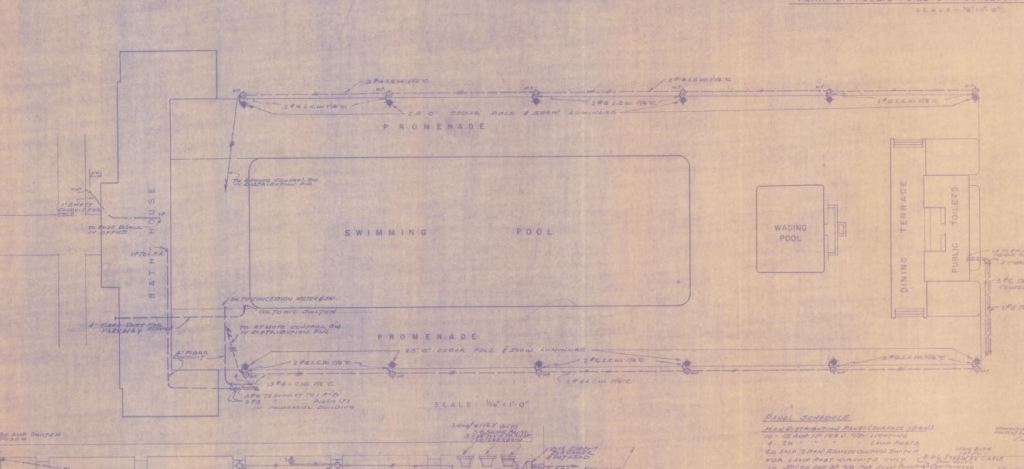

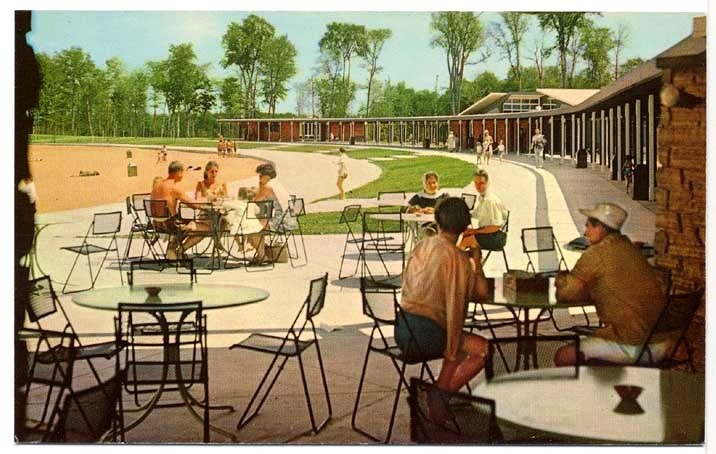

At Harriman State Park, a new beach at Lake Sebago and the Anthony Wayne Recreation Area expanded the park’s recreational capacity. With the completion of the Palisades Interstate Parkway, demand for state park facilities increased. The Lake Sebago beach development and the bathhouse addressed this demand. The new beach area could accommodate 2,000 automobiles and 10,000 patrons.

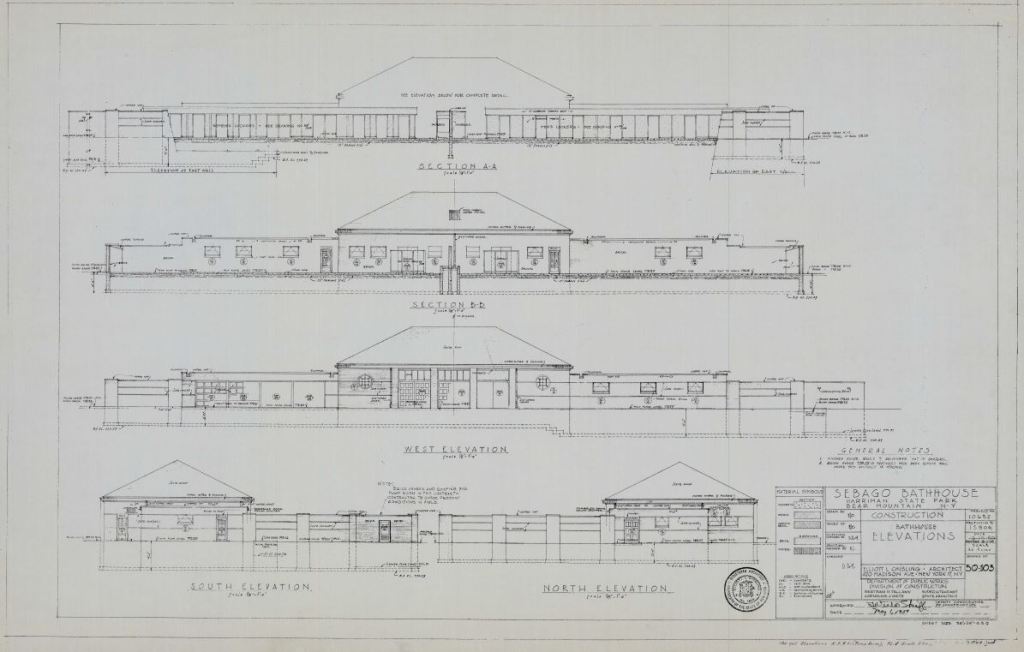

Designed by New York City architect Elliott L. Chisling, the Lake Sebago bathhouse exhibits both traditional and progressive impulses. The symmetrical form of the main block, with its hipped roof and large ocular windows, suggests classical sources. But the building’s proportions, form, limited decorative elaboration and polychrome brickwork largely account for its overall effect.

Although not precisely of modern conception, in the context of the Harriman-Bear Mountain complex, it represented a significant departure from the rustic motif that was established early and used extensively in the Palisades Interstate Park. This distinction becomes clearer when the building is contrasted with the bathhouse at Lake Tiorati, with its sloped heavy stone walls and low hipped roof.

Evangola State Park opened in the mid-1950s on the shores of Lake Erie. It represented the expansion of the Niagara region, guided in part by a 1952 regional master plan.

The design of the 1957 bathhouse illustrated the trend towards a modern park aesthetic. No longer evident are hints of the rusticity of the preceding era, either in form or material, nor traditional design sources. Instead, the building employs a rectilinear brick exterior. Its overall form is geometric, with flat roof surfaces and steel-frame windows, many of the tripartite “Chicago window” type.

In contrast to the previous era, this design program was highly economical and illuminates the key association between modern design trends and financial economy.

Also of note is Evangola’s site plan, with a crescent-shaped parking lot that anticipated the crowds that soon filled the park.

Staff Design in Central Region

In the late 1940s, the Central State Park Commission, which had operated out of offices in Binghamton, decided to build a new administrative building. The 1951 building at Clark Reservation in Jamesville placed the offices on state park land and in a centralized regional location.

Designed by Parks staff, a view of the building was published in the Conservation Department’s 1950 annual report. The building’s strongly geometric form is evident, consisting of interlocking cubic and rectangular masses, the main sections being flat roofed. While the exterior is stone, ornamentation is absent, and windows are treated more as long ribbons than individual units.

The commission met for the first time in the building in August 1951, at which time it was noted “…that the General Manager [Leonard L. Huttleston] and his design and construction staff should be congratulated for completing such an attractive and useful building for Commission headquarters.”

Midcentury Modern on the St. Lawrence River

Foremost among new state park developments in the 1950s was the 1959 completion of a new state park on Barnhart Island on the St. Lawrence River, in present-day Robert Moses State Park (formerly St. Lawrence State Park) in the Thousand Islands region.

This facility was developed by the New York Power Association (chaired by Robert Moses), in association with the St. Lawrence Seaway and a joint American-Canadian electrical generation project. The park amenities were conveyed to the Thousand Islands State Park Commission once the power-generating complex was completed.

All traces of the rustic sentiment of the prewar period are gone. The form, materials and disposition of the park buildings convey a distinctly modern architectural sentiment. The buildings and park features exhibit the crisp, clean lines of the midcentury modern style.

The 1959 picnic pavilion, designed by the New York City architectural office of Slater & Chait, depicts the evolution of the open-air park pavilion from its interwar origins. Massive trusses rise from cylindrical stone bases and support a large, single-sloped roof. On either side are stone-walled enclosures providing restroom space.

Rising from the center of the open pavilion is a large stone chimney with fireplace that mediates against the structure’s otherwise strong horizontal profile. Evident in the pavilion is an emerging modern park aesthetic: sleek, functional, and clean lined.

The crescent-shaped arrangement of the original administration building, bathhouse, concessions building and dining pavilion – linked by a continuous covered colonnade – creates Barnhart Island’s signature architectural statement.

The colonnade is characterized by its geometric forms and perforated, rectilinear roof.

The highly expressive dining pavilion is covered by an undulant, polygonal-form roof that takes the form of a symmetrical flower petal or six-pointed star. The roof is supported by twelve wood rafters that radiate outwards from the center. The principal rafters taper outward. Its bases bear on sandstone piers.

There is nothing rustic in this and other Barnhart Island buildings. They are thoroughly modern in form, treatment, and sentiment. Given the new park’s association with progress and modernity as expressed in the sprawling power project, this circumstance was fitting.

The Barnhart Island and Evangola buildings set the stage for the park architecture of the 1960s, when modernism would be fully embraced, in part due to its economy during a period of considerable expansion and growth.

This period of development in the state park system was marked by subtle transitions, with an increasing shift away from prewar design preferences to those better aligned with the postwar era. The evolution from rustic to modern park architecture indicated a change in aesthetic tastes and material choices. Additionally, some examples portray a shift in how the public used state parks and exemplify the postwar growth of visitation. Barnhart Island and Evangola State Park set the stage for the full emergence of modernism in state park architecture during the 1960s build-out of the system.

**Unless otherwise noted, images are from the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation files.

—Written by Bill Krattinger, Historic Preservation Project Director

I really enjoyed exploring

your site. good resource

GTU