Staatsburgh State Historic Site, formerly the Gilded Age estate of the very wealthy and socially-prominent Ruth Livingston Mills and her husband, financier and philanthropist Ogden Mills, sits along the eastern bank of the Hudson River in the mid-Hudson Valley.

Commanding a view of the river and the Catskill Mountains, the estate’s Beaux-Arts mansion was once the scene of elegant house parties each autumn weekend for the glitterati of American society. The home is still filled with the original furnishings, art and décor chosen by Ruth and Ogden Mills after its redesign by prominent architect, Stanford White, circa 1895, from a 25-room home built by Ruth’s great-grandfather into the 79-room house we see today.

Touring the home, one is struck by its opulence but also by its regal formality: Ruth’s bedroom, with its hand-carved bed on a platform, surmounted by a lavish baldachin (a kind of ceremonial canopy), and surrounded by walls of raspberry silk brocade, seems well-suited for a queen of society.

Among her peers, Ruth was known for her acumen as a hostess, her exclusivity (reportedly opining that there were only 20 wealthy families in New York worth knowing), and her imperious poise. As one of her contemporaries said:

“[Ruth Mills] would invite [guests] to her house…greet them with a limp hand, languidly extended, and a far-away expression, and then apparently forget their existence. They were chilled but impressed.”

While it might be difficult to image, this reserved, aloof woman also had an athletic side uncommon for most women of that time. She helped build the popularity of the sport of figure skating as an early prominent practitioner and benefactor. And she also had a hand in the opening of one of the earliest indoor refrigerated ice rinks in North America.

My research into her history revealed some parallels with my own life. I have been a competitive figure skater for more than 20 years, and am a U.S. Figure Skating Gold Medalist after passing tests in four disciplines including freestyle and ice dancing. Now, I coach young skaters at a rink in nearby Saugerties.

For me, like it might have been for Ruth Mills, skating is athletic and artistic, allowing one expression through music and dancing.

Ruth Mills’ skating was widely recognized during her time. An 1893 New York Herald article praised her as an accomplished and graceful ice skater. According to the newspaper, Ruth started skating with her twin sister Elisabeth when they were girls. That would have been during the 1860s, which was a time when skating was starting to become very popular in the United States. By that time, men and women were skating together on the same ponds (one of the few athletic activities where both genders were involved together), and even the press was supportive of women skating, extolling the health benefits.

Figure skating was the first sport where women participated for the pure joy of it and where their participation with men was widely accepted. Skating became so popular in the mid-19th century that there was an estimated crowd of 100,000 on the pond in New York City’s Central Park on Christmas Day in 1860.

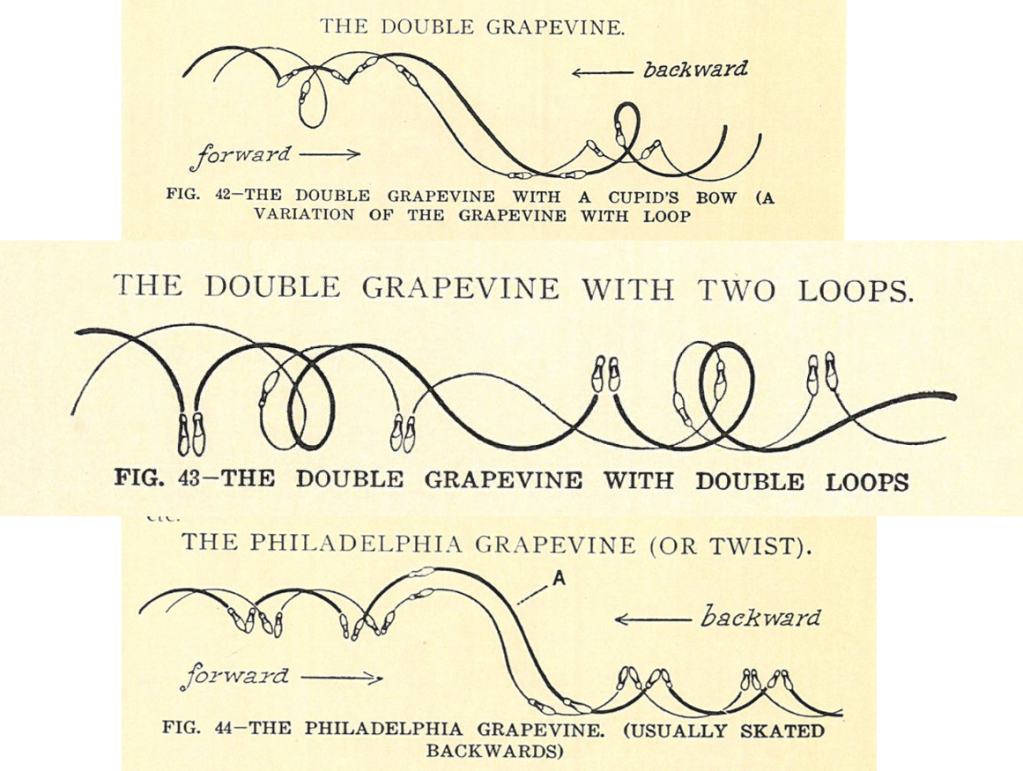

Newspapers of the day took note of Ruth Mills, with one reporter writing in the 1890s: “Mrs. Ogden Mills is quite too graceful and proficient. As if by common assent, the others stop a moment to watch her do the double Philadelphia grapevine, about the most difficult gyration on ice known to the expert.” By this point, Ruth Mills would have been about 40 years old.

Watchers of skating today might not recognize this move, but the double Philadelphia grapevine was seen as one of the most complex techniques of its time. As described in a contemporary magazine: “The double grapevine is the same as the single, except that a loop is introduced at the beginning and also at the end of the figure. It is executed, as in the single grapevine, by passing the right foot in front of the left foot with the chain step; but instead of making a half revolution, as in the single, the body is swung completely around by the means of two turns on the right foot and an inside loop on the left.”

While newspapers of this time made a habit of fawning praise over wealthy and powerful members of New York society, it is clear that Ruth was an accomplished skater. To the modern skater, the fact that Ruth could maneuver gracefully on ice, in the corset and multiple layers of clothing covering her from neck to foot, which Gilded Age women were required to wear, makes her ability even more impressive.

Given Ruth Mills’ self-composed demeanor, I find it hard to imagine her falling on the ice in front of people. But she must have started skating very early in life and put in much practice to become as skilled and confident as she was. Some of that early practice likely must have been on the rough ice of the frozen Hudson River at Staatsburgh when she was growing up.

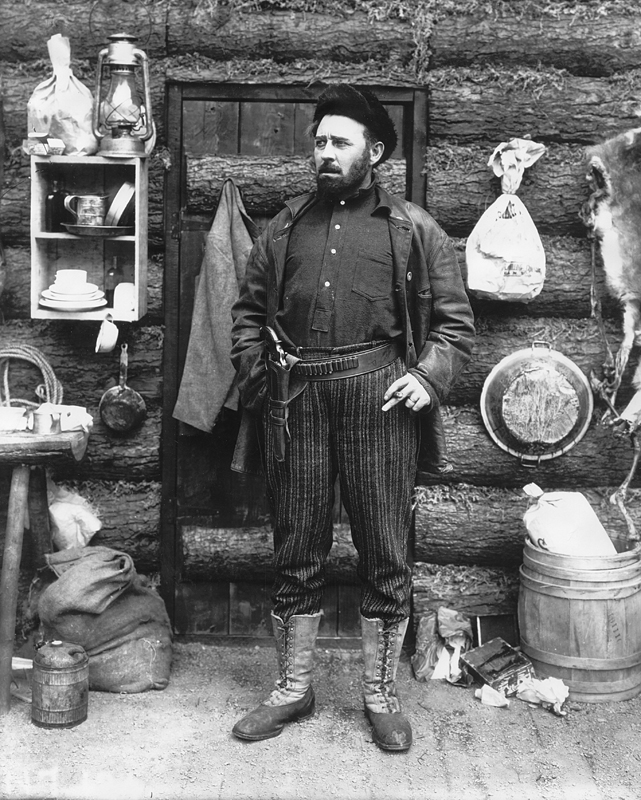

We know that the river was a very popular place to skate and we have a photo of the estate superintendent’s family skating in 1916. The cove area near the estate’s powerhouse was a popular place for local village residents to skate.

While Staatsburgh was the primary residence of Ruth and Ogden Mills in the autumn, like many of their social set, the couple traveled with the seasons. New York City was where the elites dwelled in the winter months, as it was the season of the opera, and of lavish balls given in assorted Fifth Avenue mansions.

Whether dancing or ice skating, the elites of New York always preferred to pursue their leisure apart from the common folk, and in 1896, many of the wealthiest families, including Ruth and Ogden Mills, contributed to the construction of one of the earliest indoor ice rinks built in New York City, the St. Nicholas Skating Rink.

When skating depended on a pond or river to freeze, skaters were at the whim of mother nature (sometimes they had only 15 to 20 days a season to skate), but after the creation of indoor ice surfaces, the skating season would extend much longer.

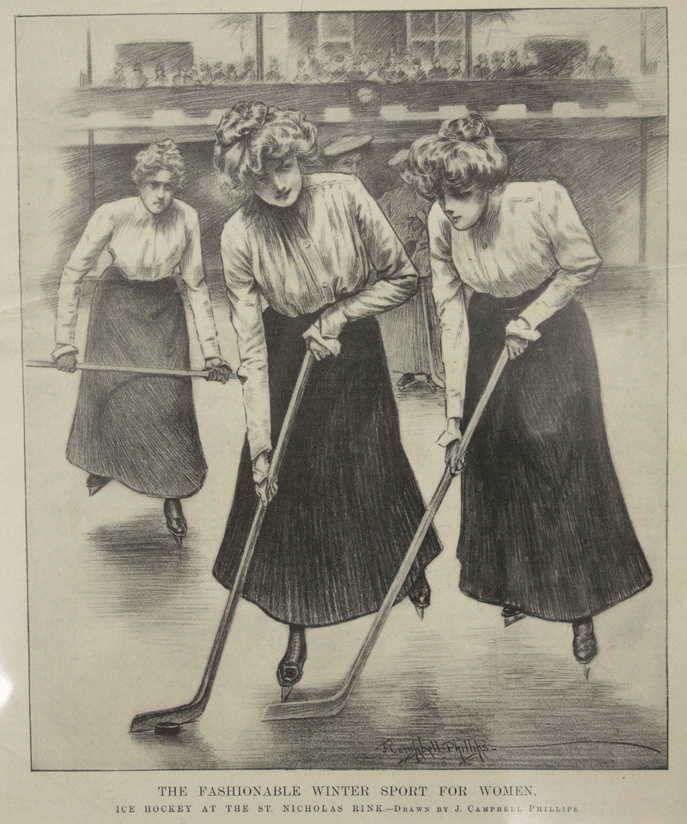

The St. Nicholas Skating Rink also was one of the earliest indoor ice rinks made of mechanically frozen ice in North America. The arena also was the site of the first game between women’s ice hockey teams in the United States, when in 1917 the St. Nicholas team defeated Boston 1–0.

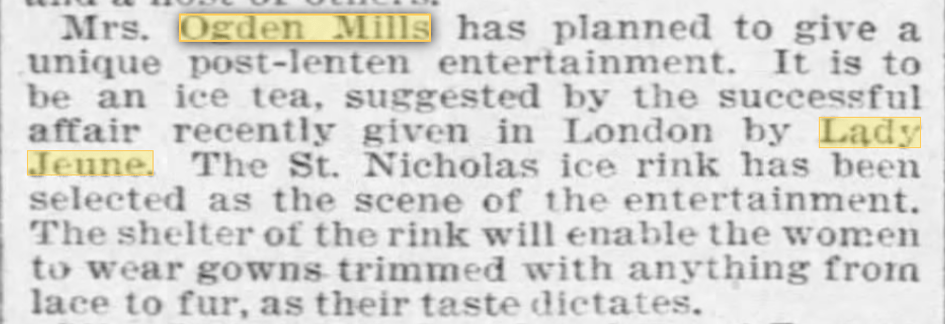

Building this rink was an investment of $300,000 (more than $9 million today) contributed principally by elite patrons like the Mills. Located on West 66th street, the rink was less than four blocks from the couple’s mansion, and contemporary newspapers accounts stated that Ruth Mills skated there nearly every morning.

Shortly after the rink opening, an article in The New York Times noted that Mrs. Mills was to host an “ice tea.” Not the popular beverage, this exclusive social event included both skating on the rink and tables to consume tea and light refreshments.

So here, Ruth Mills got to combine her interests in both luxurious entertaining and skating. Sadly, the St. Nicholas Rink was demolished in the 1980s after a long history of hosting skating and boxing matches.

If you would like to know more about this family, and the Gilded Age lifestyle they led and the mansion in which they lived it, make a trip to Staatsburgh State Historic Site the Taconic Region.

Nearly 200 acres of the historic Mills estate is within the Ogden Mills and Ruth Livingston Mills Memorial State Park, which is open every day, all year, from sunrise to sunset, with no fee for park entry. It includes the Dinsmore Golf Course, one of America’s oldest golf courses, as well as trails for hiking and cross-country skiing.

Guided tours and special programs are offered at the Mills mansion year-round; for programs information and hours of operation, call (845) 889-8851, or visit our website.

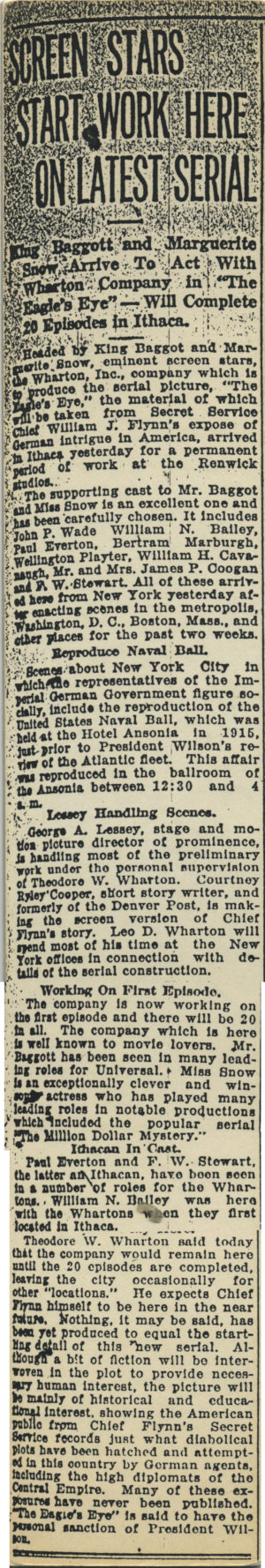

Cover Photo: The St. Nicholas Skating Rink in New York City. Unless otherwise noted, all photos courtesy of NYS Parks.

Maria Reynolds, Ph.D., Historic Site Assistant / Curator, Staatsburgh State Historic Site

Reynolds has given lectures at Staatsburgh on “Gilded Age Tea & Talk” program series, presented each winter. Now in its sixth season, this program series offers guests the chance to enjoy the site’s custom tea blend, created by Harney & Sons, along with scones, clotted cream, tea sandwiches and sweets, served in the mansion’s opulent formal dining room while listening to talks on various aspects of Gilded Age history.