Now 90 years old, Bruno Kaiser remembers arriving 75 years ago at a U.S. Army base along the shore of Lake Ontario, a day that ended his family’s long struggle to escape death during World War II at the hands of the Nazis.

“We felt safe, which had been our biggest worry for so long,” said Kaiser. “At last, we felt perfectly safe.”

On Aug. 5, Kaiser returned to Fort Ontario State Historic Site, along with 18 other surviving refugees of the Holocaust, to gather for a final reunion to remember their lives at the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter.

Surrounded by a fence and guarded by military police, the base at Oswego was America’s only wartime sanctuary for escapees of Hitler’s genocide.

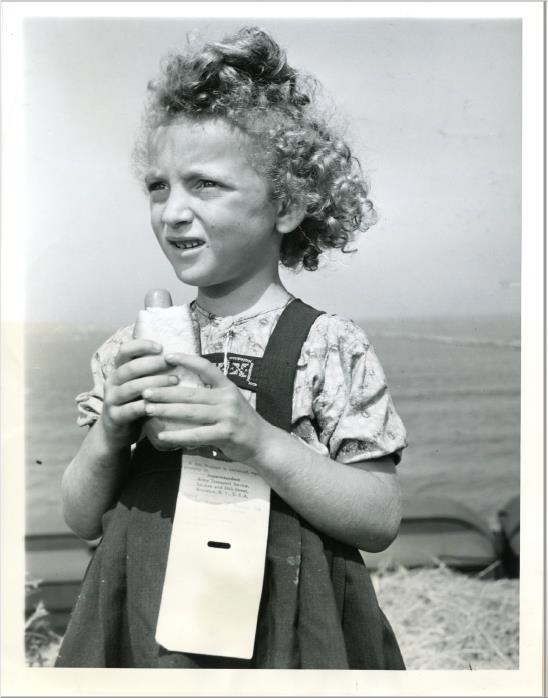

Kaiser was one of 982 European refugees who arrived at the fort Aug. 5, 1944, about a month after the first accounts of a liberated Nazi death camp horrified the world.

Coming from 18 different countries, the new arrivals were predominately Jewish, but their ranks also included some Catholics, Orthodox and Protestants. Having escaped annihilation in their homelands through a combination of luck and pluck, the refugees came to the U.S. under a program created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt., whose selection of Fort Ontario stemmed from his earlier time as U.S. Secretary of the Navy and later as Governor of New York state.

Providing security, shelter and food _ but not the ability to leave _ the camp was to be home to the weary refugees for the the next 17 months. After the war’s end, their fate ended up drawing national attention over whether they should be forced to return to their devastated countries.

In late 1945 Roosevelt’s successor, President Harry Truman, gave the refugees the choice of remaining in the U.S. or going back to Europe. Like Kaiser, most chose to stay, building lives and families in their new homes.

Today, no more than 35 former camp residents remain alive, said Paul Lear, manager of the historic site and co-organizer of the reunion and commemoration. He said it will likely be the last such gathering for a group whose members are now in their mid-70s to early 90s.

More than 600 people attended the reunion, said Lear, including Ambassador Dani Dayan, Consul General of Israel in New York; Rebecca Erbelding, a historian with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.; Michael Balanoff, President and CEO of the Jewish Federation of Central New York; Geoff Smart, son of Refugee Shelter Director Joseph Smart; and Oswego Mayor William Barlow Jr.

Kaiser’s story is both unique and similar to that of his fellow escapees, spending months or years on the run, trying to stay ahead of arrest and shipment to concentration camps. Along with his father, mother, and two grandparents, Kaiser had fled Yugoslavia in the spring of 1941 after his father had been arrested – and miraculously released after only a few days – in the wake of the Nazi invasion and takeover when Jews were being rounded up.

“My father decided we should leave _ quickly,” said Kaiser, so the family caught a train bound for the safety of the Italian-occupied Adriactic coast. During the trip, the train stopped in a switching yard.

“Across from us was another train, this one with prisoners being taken away by the Nazis. I could see their faces. That is how close we came,” said Kaiser. “The rest of my (extended) family, who did not leave, ended up being wiped out.”

His family remained in relative safety under Italian control until September 1943, when the Italian government surrendered to the Allies, which led the Nazis to attack and occupy all Italian-held territory. The Kaiser family then gained passage on a small ship that took them to an island occupied by the Allies.

From there, the family was shipped to the Allied-controlled portion of the Italian mainland, and taken with several hundred other refugees to the port of Toranto for shipment to North Africa. But the family decided on its own to stay in Italy, and was helped by a local stranger to find an apartment. And it was there, while the teenage Bruno was attending a local high school, that the family learned of Roosevelt’s program for America to accept a very small number of European and Jewish refugees.

“We applied, and because we had family in Cleveland and Chicago, were accepted. The Oswego camp was a peaceful place. I went to the public high school, with about 40 other kids from the camp,” said Kaiser, who recalled he had to “learn English from scratch” to go along with his other languages: Croatian, Italian and German. “The people of Oswego were nice to us. There was never any anti-Jewish anything.”

After being released from the refugee camp in January 1946, the Kaiser family joined relatives in Cleveland, their son finishing his senior year of high school there. He later earned an electrical engineering degree from Ohio State University. Now retired after working for various companies, he is father to three daughters and two grandchildren.

Asked what the lesson of Fort Ontario is for people today, Kaiser paused. “It is that anti-Semitism rears its ugly head every once in a while. And it is happening now.”

Tellingly, a 1981 stone monument to Fort Ontario camp was vandalized shortly after being installed, with the word “Jewish” partially chipped away and its corners knocked off. Site officials decided to leave the monument as it is as a reminder of the dangers of anti-Semitism.

To create the camp, Roosevelt avoided rigid immigration quotas by identifying the refugees as his “guests,” a status that gave them no legal standing and required them to sign documents agreeing to return to Europe at the end of the war. In September 1944, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the camp to draw attention, writing about it her weekly newspaper column. After the war, camp director Joseph Smart stepped down from that post to form a national campaign that pushed for the refugees to be given the choice to stay in America, a step that was taken by President Truman.

Later, the state historic site at Fort Ontario was established and opened to the public in 1953.

Linda Cohen came to the Oswego reunion from her home in Michigan, to remember her parents, Leon and Sarinka Kabiljo, who lived at the camp.

“My parents were married on April 6, 1941, the day the Nazis invaded Yugoslavia. They were on the run for three years, hiding in the forests with the partisans. My mother worked with them as a nurse,” she said. Once Italy surrendered, the Kabiljos went to that country, and while there also learned of the U.S. refugee program.

“My older sister was born nine months to the day after my parents arrived in Oswego,” said Cohen. “My mother told me that refugees cried when they got to the Oswego camp. They had beds with sheets, and most had not slept on sheets in years. She told me the camp director said to them: “When there is a knock on your door now, it will be a friendly one.”

Her parents eventually settled in Baltimore, where Linda was born in 1951 and where Leon lived to age 94 and Sarinka to age 92. Cohen wrote a book about their story entitled Sarinka: A Sephardic Holocaust Journey: From Yugoslavia to an Internment Camp in America.

At the start the reunion ceremony, a recording was played of Neil Diamond’s 1981 song America. “I have heard that song a thousand times,” said Cohen. “But sitting here that day, near where the refugee barracks and my parents used to be, it was like they were that song.”

Currently, the National Park Service is studying whether Fort Ontario should receive national park status, as part of the Fort Ontario Study Act passed by Congress and signed by President Donald Trump in 2018. The site is open to the public and various activities and exhibits run throughout the year.

During his tour of the fort, Israeli Ambassador Dani Dayan praised the people of Oswego for their warm embrace of the camp, with residents often coming to the fence to visit the refugees, passing food and other gifts. “The people who welcomed Holocaust refugees into Oswego were a shining example by saying with their actions that they were not indifferent, that they cared about them and wanted them to be there while the rest of the world rejected refugees solely because they were Jewish,” he said.

During a ceremony near the site of the former barracks, Lear recalled the words of refugee Dr. Adam Munz at the first reunion in 1981: “The Oswego Refugee Shelter was and has remained for me, and I suspect for some others as well, a paradox. It symbolized freedom from tyranny, oppression and persecution on the one hand, and yet there was a fence, a gate that locked and guards were felt necessary to contain us at the very time we longed for the kind of freedom this country stood for and professed. Our country’s immigration laws continue to be paradoxical.”

Lear also recalled General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s prediction that someday people would deny that the Holocaust ever happened. To protect against that, he ordered U.S. troops in Europe to tour concentration camps to bear witness that it did.

Now, in a time of rising anti-Semitism and attacks on Jews, Lear said Fort Ontario, while no longer an active military base, remains “a fortress against forgetting and denying the Holocaust.”

Resources:

Erbedling, who has also written a book on subject, entitled Rescue Board: The Untold Story of America’s Efforts to Save the Jews of Europe, said given the age of the surviving former refugees: “For everyone younger than 75, it is our job to remember their story.”

In 1987, the public broadcasting station in Rochester, WXXI, made a documentary about the camp. It can be found here.

Cover Photo: During a visit to the Fort Ontario museum, Yugoslavian refugee cousins Ella, David and Rikika Levi touch a section of the wire fence that used to surround the camp. Behind the fence is a 48-star flag that used to fly over the fort during World War II.

Post by Paul Lear, Site Manager of Fort Ontario Historic Site, and Brian Nearing, Deputy Public Information Officer.