Jones Beach has always had a special relationship to energy. Located on Long Island’s South Shore just 20 miles from New York City, Jones Beach State Park is on a barrier island shaped over hundreds of thousands of years by the energy of advancing and receding glaciers, and later by the energy of the sun currents of ocean water and wind carrying sand along the coast.

Originally called Short Beach, this barrier island was inaccessible to the public. To create the state park almost a century ago, planners and engineers harnessed the energy of machines and human labor, moving sand and plants to expand the island, and building roads, amenities, and the Art Deco tower and buildings so recognizable today.

Today, energy is everywhere on Jones Beach. It’s in the dramatic dive of a predator like the Common Tern, and in the bright sun that drives photosynthesis of the Seaside Goldenrod, Beach Grass or Beach Pea. It’s in water that brings migratory species and the winds that distribute seeds and carry pollinators from plant to plant. But energy is also present in the engines of the cars that bring visitors to the Park, and in the historical construction of the parkways that they follow to get here.

In an era of climate change, and in the context of New York’s growing commitment to developing renewable energy systems, the Jones Beach Energy & Nature Center aims to help New Yorkers understand the fundamental ways human energy consumption and energy infrastructure continue to shape our natural environment.

To further this mission, the Center recently released Energy & Us, a 300-plus page curriculum for high school students that is available to view or download for teachers and school districts at no cost through jonesbeachenc.org/curriculum.

The goal of the program is to inspire young people to think critically about how energy shapes their landscapes and their lives, as well as their own roles in energy systems and ecosystems that surround them. With the beach itself as a classroom, Jones Beach State Park is the perfect place to learn about energy from sunlight, sand, wind, and water.

NATURAL ENERGY AT JONES BEACH

Let’s start by considering the very essence of Jones Beach – a simple grain of sand. A crystal structure composed of millions of molecules, typically of the compound silicate (SiO2), sand is held together with very strong bonds. By comparison, bonds in a drop of spray from the ocean are much weaker. Much less energy needs to be added to water than to sand to trigger what is known as phase shift: A puddle of water will quickly evaporate in the sun, while a similarly sized patch of sand won’t melt. Sand will melt with enough heat, as in done in glass-making, but does sand melt in nature?

Consider when lightning strikes a beach, it creates melted and recrystallized sand formations called fulgurites, also known as “fossil lightning.” Lightning possesses tremendous energy — the core of a lightning strike can reach 53,500 F — but only makes contact with a relatively small surface. The strike quickly heats the sand to a high enough temperature that its chemical bonds are broken. Fulgurite then forms as the energy transfers out of the melted sand into the surrounding ground and air, and the melted matter becomes solid again, forming this unusual form of fused sand.

Have you ever gone swimming in the late summer or early fall, and found the water to be warmer than the air? Solar energy that is absorbed over the course of the summer dissipates in the fall more easily from land and air than from water. This is because water is a relatively poor conductor; energy moves through it with difficulty, so water is slow to heat and slow to cool.

Air is a good insulator and a poor conductor, which is why fur and down help keep animals warm. It’s not the quantity of hairs or feathers that matters, but rather the layer of air trapped within that stops energy from being conducted out of the body into the surrounding air. Birds fluff up during the winter to trap more insulating air in their feathers.

When sunlight hits the beach, radiant energy transforms into the kinetic energy of excited electrons in the sand, which vibrate, producing what we experience as warmth. Maybe even too much warmth on a sunny day, as anyone who has walked barefoot knows! The excited electrons also release new photons, wave particles that carry energy away from the sand and produce what we perceive as glare.

ENERGY DRIVES ECOSYSTEM CONDITIONS

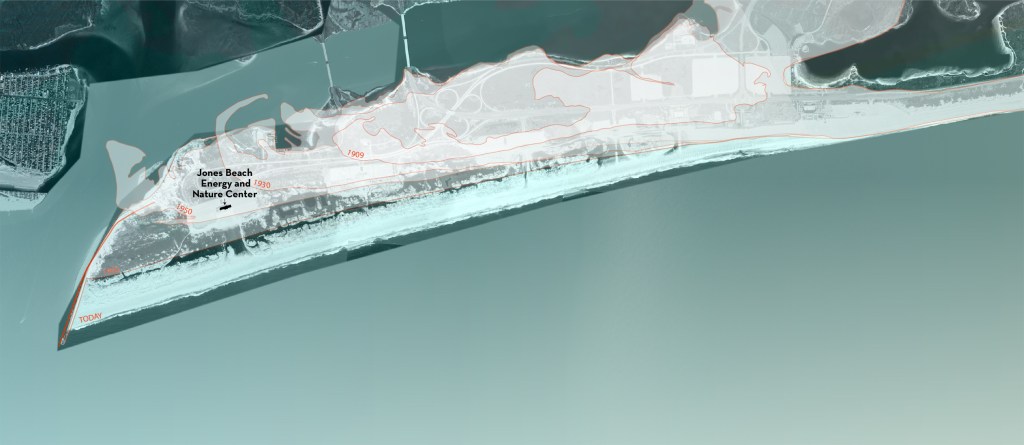

At Jones Beach, dominant winds flow from the west and the north, pushing sand dunes gradually towards the sea. Meanwhile, ocean currents flow parallel to the mainland, pushing sand from east to west and moving the shoreline westward. A jetty constructed in the 1950s at the West End interrupts these currents, causing sand to accumulate on the eastern side while the western channel remains open.

Winter and storm-season waves typically contain more energy, pulling more sediment off the beach and into the water in a process called erosion. When large waves wash over dunes during high tides and storms — a phenomenon called “overtopping” — dunes can flatten and shift. In summer, ocean currents, waves, and winds typically bring sands back onto the beach and dunes in a everchanging cycle.

Water and winds can also influence how species move through Jones Beach. Birds, winged insects, fish, phytoplankton, and various other organisms travel on currents in the air and water, and currents also distribute seeds, eggs, and nutrients that organisms need to survive. Local examples of this include plankton that float on ocean currents, providing food for larger marine animals; shorebirds that depend on the strong sea breeze; and grass seeds spread by water and wind. Although major storms can decimate local populations of some species, most of the plants and animals of this ecosystem are adapted to these natural processes.

ENERGY SHAPES PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE AND PRIVATE LIFE

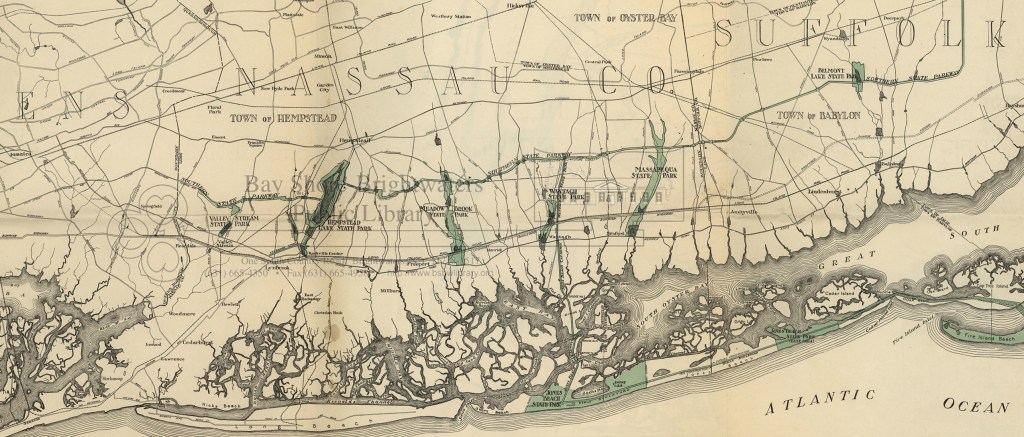

When planner Robert Moses envisioned Jones Beach State Park in the 1920s, he recognized that the automobile would have an increasing role in daily American life.

The rise of cars was coupled with another innovation by automaker Henry Ford – the assembly line that allowed for costs to be reduced, creating a new class of workers with enough disposable income to purchase the goods they produced, and with more leisure time to allow travel.

Jones Beach State Park was one of the first and most prominent parks to connect this growing urban middle class to the environment.

In 1924, as the new chairman of the State Parks Commission and President of the Long Island State Parks Commission, Moses began planning a system of “Parks and Parkways” to connect car-owning city residents to beaches and parklands across Long Island. Moses envisioned parkways as an extension of the parks themselves: green spaces that transported urban dwellers to a beautiful natural landscape.

Jones Beach opened in 1929 as a triumph of 20th century engineering. Forty million cubic yards of sand were dredged from the bay to widen the beach and raise its elevation up to 12 feet. Workers hand-planted a million native Beach Grass plants to prevent the taller dunes from blowing away in the wind.

Moses’s plan for parks and roads across Long Island reflected a new approach to “nature,” one of landscapes constructed intentionally for public enjoyment. The parkways also helped spark a new era of Long Island suburbanization, which greatly increased consumption and the demand for energy.

Many different types of energy come together at the Jones Beach Energy & Nature Center. As climate change impacts the globe with rising seas and stronger storms, Jones Beach will model the positive possibilities for access and use of energy. Solar panels that power the Center represent New York’s commitment to expand renewable energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions that are driving climate change. Resilient design modeled by the building itself will be key as New York’s communities adapt to rising sea levels and changing weather patterns.

There has never been a more important time for New Yorkers to understand the connections between energy, nature, and society. With the Energy & Us curriculum, young people throughout the state can begin to reconsider about how those forces shape their own lives, and how they can engage with them to transform the future.

Cover shot – Jones Beach Energy & Nature Center, Michael Moran/nArchitects

Post by Olivia Schwob, a writer, researcher, and editor interested in human geography, political economy, and public things. Olivia was Developer of the Energy & Us curriculum from 2020-2021, Curatorial Team Writer for the Jones Beach Energy & Nature Center from 2019 – 2020, and Managing Editor of Urban Omnibus, a publication of the Architectural League of New York, from 2016 – 2019. She lives in Brooklyn.